In the fall of 1889 sixty five Galician emigration agents and their associates (including state railway employees) were charged with fraud and other crimes in the course of facilitating emigration to America. At a time when emigration from the Habsburg and Romanov Empires to the United States was beginning its precipitous rise to historic levels after the turn of the century, domestic concerns about what kinds of people were going, under what conditions, and with what potential to maintain financial ties to their homelands all permeated the discussion around the trial, held in Wadowice southwest of Cracow. Many of the middlemen facilitating passage to trans-Atlantic ships out of Hamburg and Bremen came from Jewish backgrounds, while many local opponents of emigration, if not blatantly anti-Semitic, were increasingly fretting about the health of the remaining population (meaning a tangle of both medical-physical and organic-political characteristics). The popular press painted the accused as “human traffickers,” “vampires,” and “slave traders and bloodhounds,” feeding a strong undercurrent of anti-Semitism. (See the authoritative account by Tara Zahra.) The “echo of the Wadowice trial reverberated across all of Europe,” fostering the conviction among local patriots that “the protection of native land and rational internal colonization should emerge from the fog of fantasies and good intentions and pass as soon as possible into the sphere of accomplished deeds.”

Large-circulation newspapers like Neuigkeits Welt Blatt in Vienna made certain that their readers could not miss the Jewish lineage of many of the shipping agents.

After months of testimony featuring hundreds of witnesses, the lead accused were sentenced to several years in prison. During the prolonged sensation that was the court trial, “Russian influenza” made its epidemic return to Central Europe, traveling quickly by rail and shipping routes from the northeast to the south and west. Though its symptoms were much less dramatic than cholera, influenza hit perhaps 40% of the Hungarian population that winter, for example, and as much as half of the German population, though the associated mortality rates were quite low.

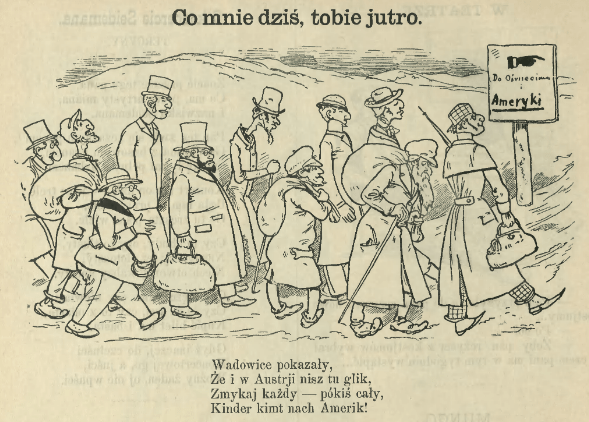

There was a mean-spirited Polish cartoon related to the trial. (The text contains Yiddishisms, so my rendering is surely problematic.)

What’s for me today is for you tomorrow.

(sign pointing to the Promised Land of America)

Wadowice showed

That in Austria, too, good fortune is not here,

Each keeps his mouth shut until everyone’s

Children come to America!

(Mucha, Warsaw, 1890)

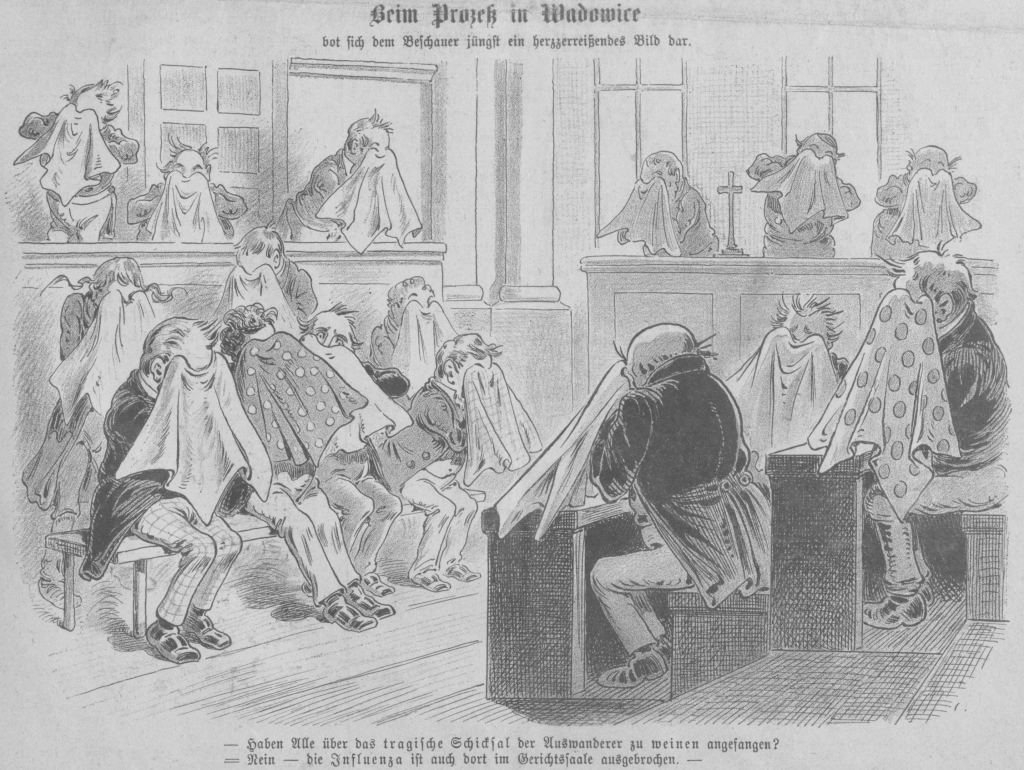

The cartoon below provides an uncomfortable linkage between the trial and the epidemic.

At the trial in Wadowice a heartrending picture presented itself to the onlookers.

“Have you started crying about the tragic fate of the emigrants?”

“No, influenza has broken out in the courthouse.”

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1890)