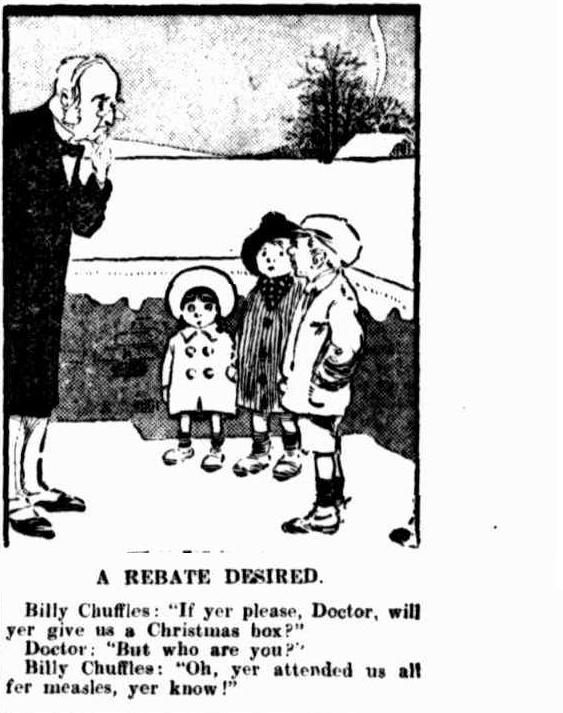

(Western Mail, Perth, 1913)

(Compare this German version)

(Western Mail, Perth, 1913)

(Compare this German version)

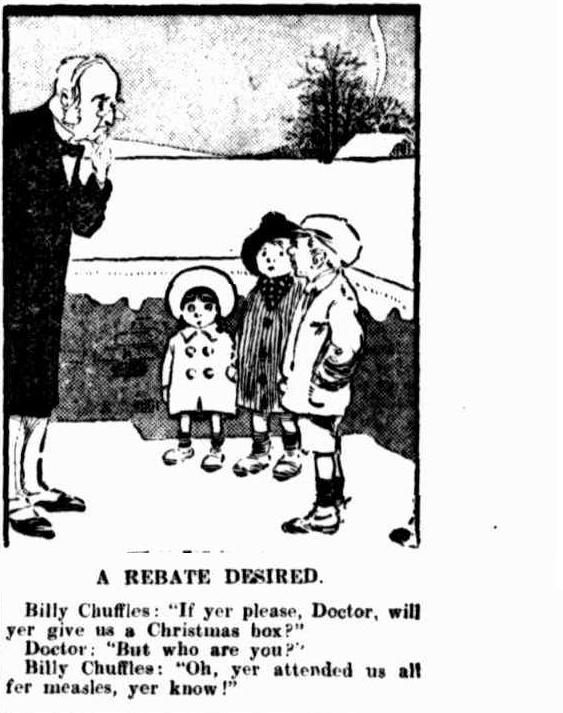

“The time has arrived when drastic steps should be taken by the Council to remove a number of the dilapidated structures which exist.”

Health Board (to slum landlord as Typhoid lurks in the background): My methods are not nice, but neither is the company you keep.

(Western Mail, Perth, 1907)

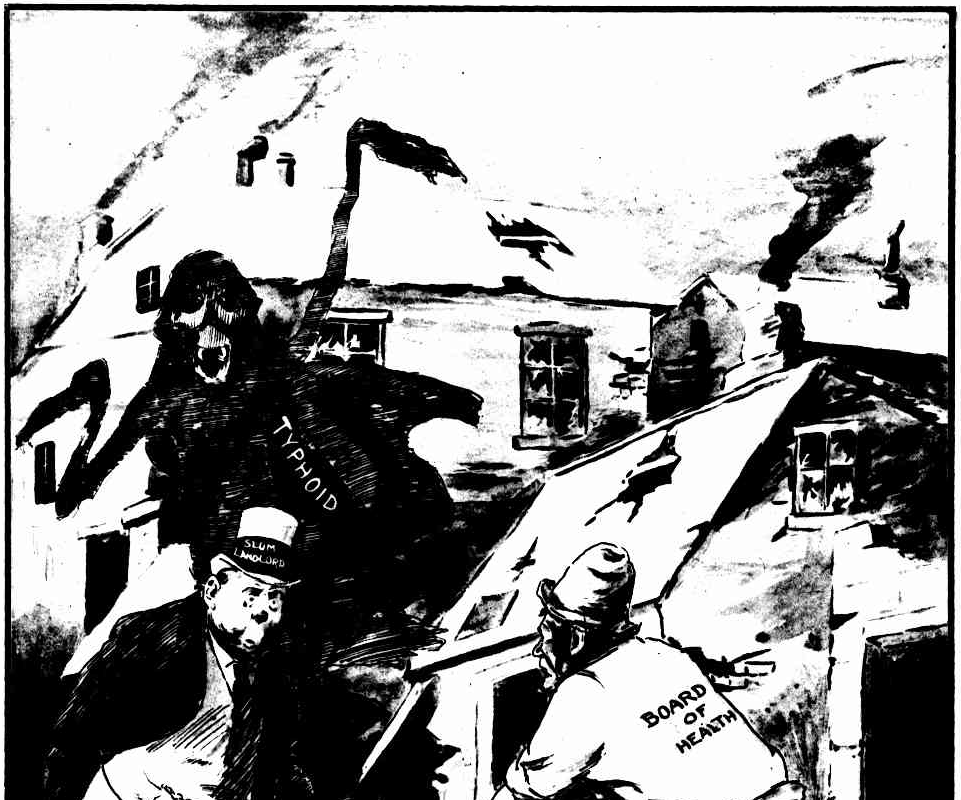

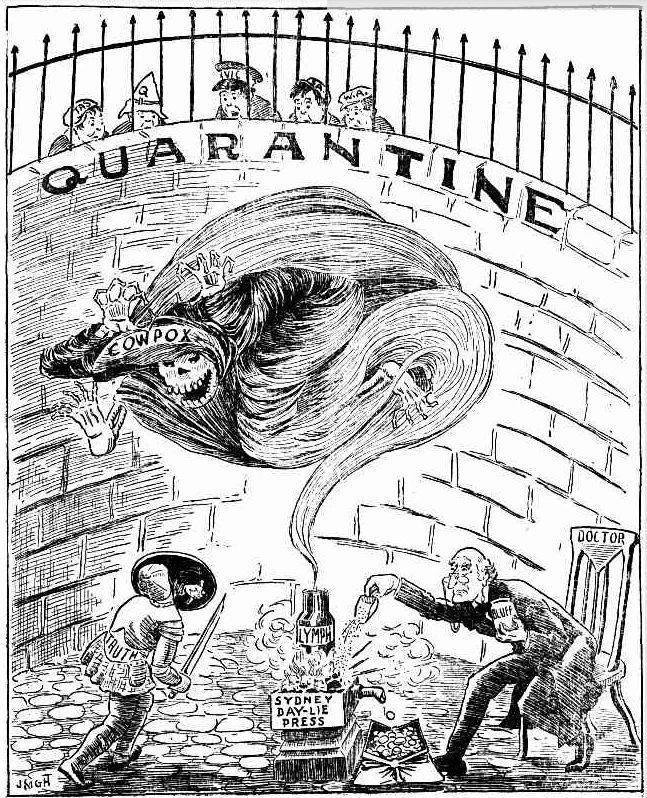

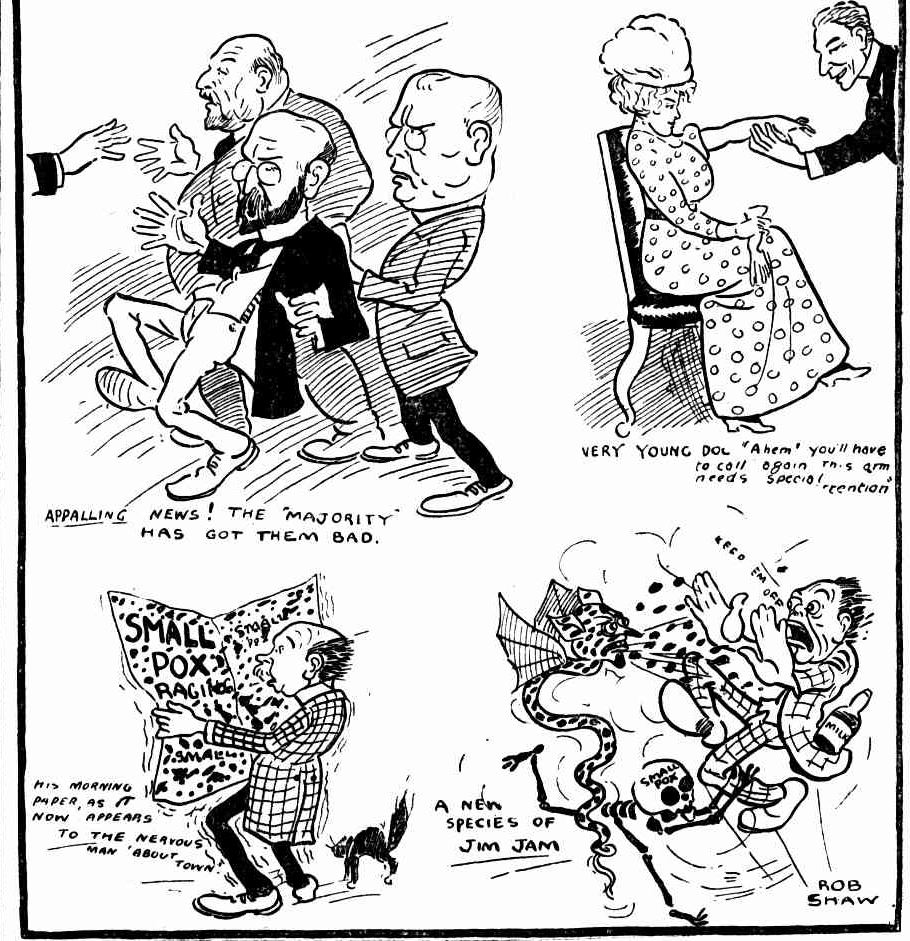

In 1881 Sydney, Australia, suffered a smallpox epidemic whose earliest infections likely stemmed from China, with the authorities once again resorting to strict quarantine. In this cartoon the nervousness about harbor connections to ships quarantined offshore invited a play on a Gilbert & Sullivan ditty.

(Sydney Punch, 1881)

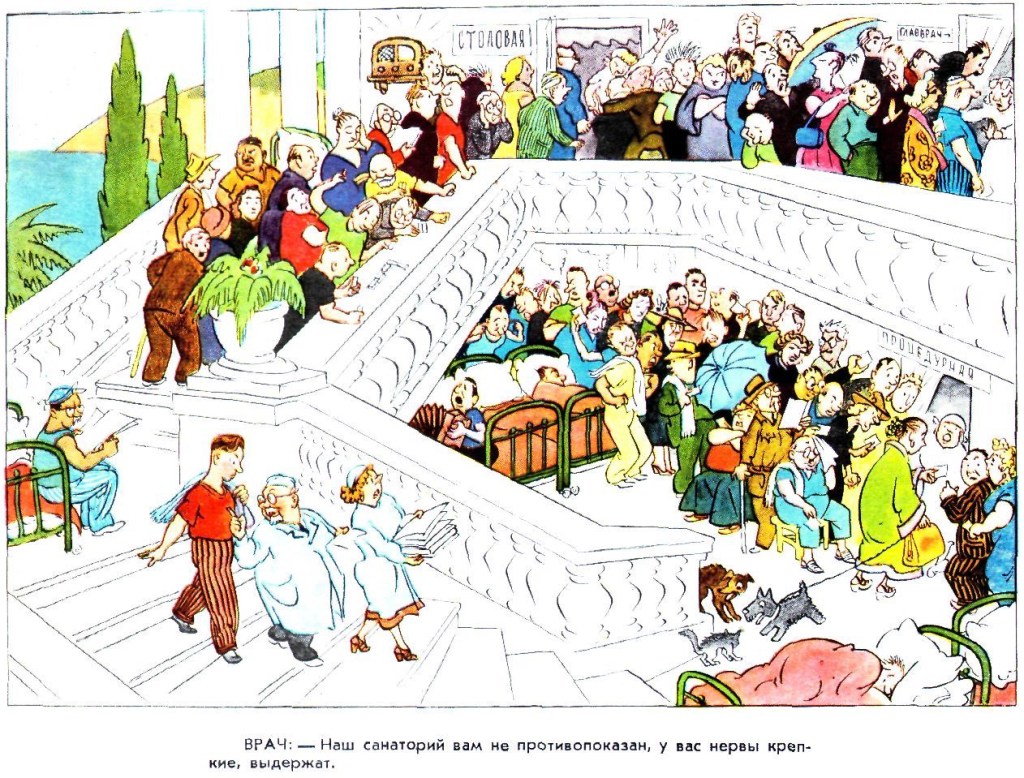

Doctor: “Our sanatorium is not counterindicated for you, you have strong nerves, they can handle it.”

(Krokodil, Moscow, 1955)

(Public health and disease themes largely disappear from Krokodil after the 1930s, when the Soviet health system finally developed sufficient capacity to serve a burgeoning urban middle class. Yet a Crimean sanatorium like the one depicted here was still a precious resource in high demand, and gentle satire of middle-class aspirations remained a Krokodil specialty.)

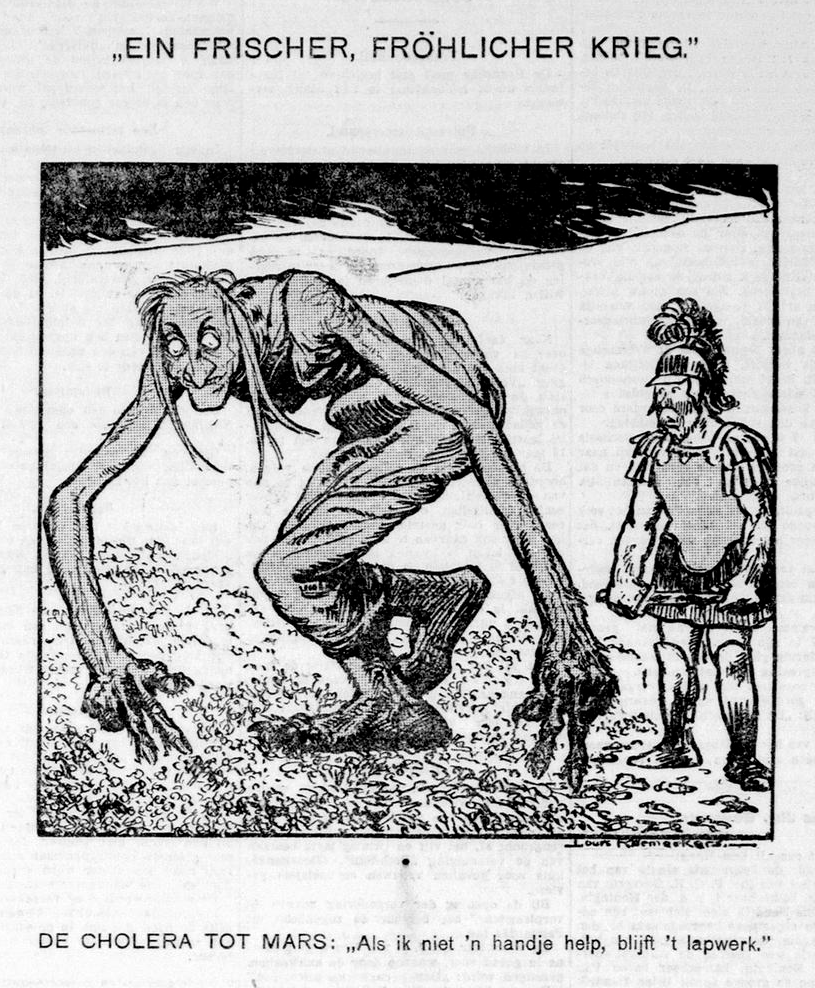

Cholera to Mars: “If I don’t lend a hand, it’ll just be patchwork.”

(De telegraaf, Amsterdam, 1912)

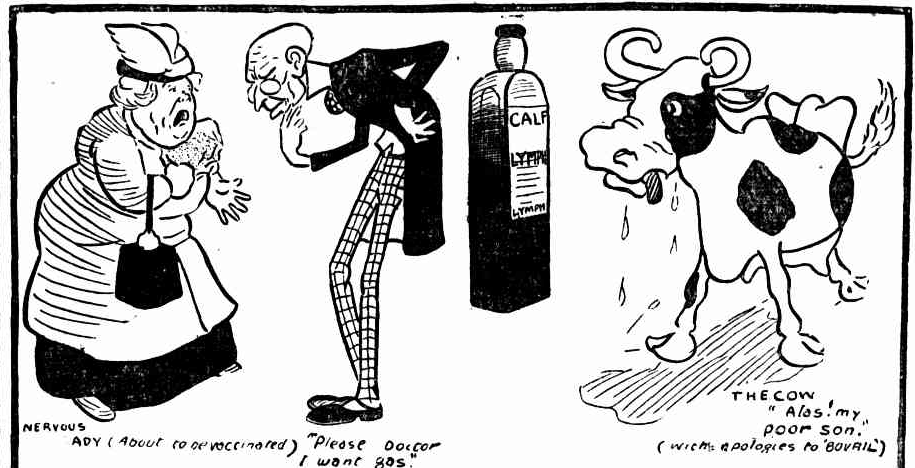

How the dodge is worked: And how it is being fought.

(Truth, Sydney, 1913) (During a smallpox scare, compulsory vaccination seems to have aroused considerable opposition, including the sentiment that it constituted “a gross and filthy idolatry, an arrogant superstition, a giant delusion, deified as scientific by the medical fraternity.”)

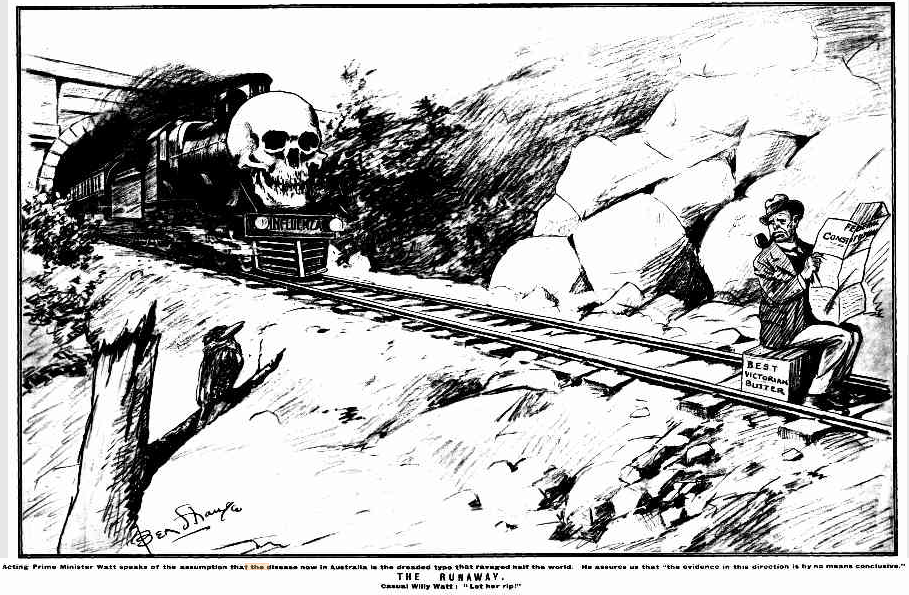

Acting Prime Minister Watt speaks of the assumption that the disease now in Australia is the dreaded type that ravaged half the world. He assures us that “the evidence in this direction is by no means conclusive.”

Casual Willy Watt: “Let her rip!”

(Western Mail, Perth, 1919) (Sign between skull and cowcatcher reads “Influenza.”)

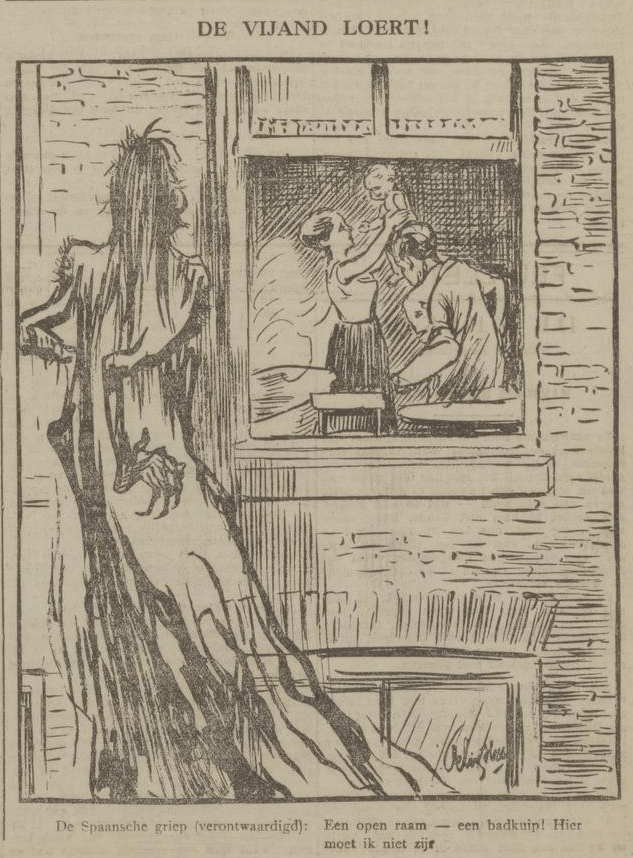

The Spanish Flu (indignant): An open window — a bathtub! I shouldn’t be here.

(De courant, Amsterdam, 1920)

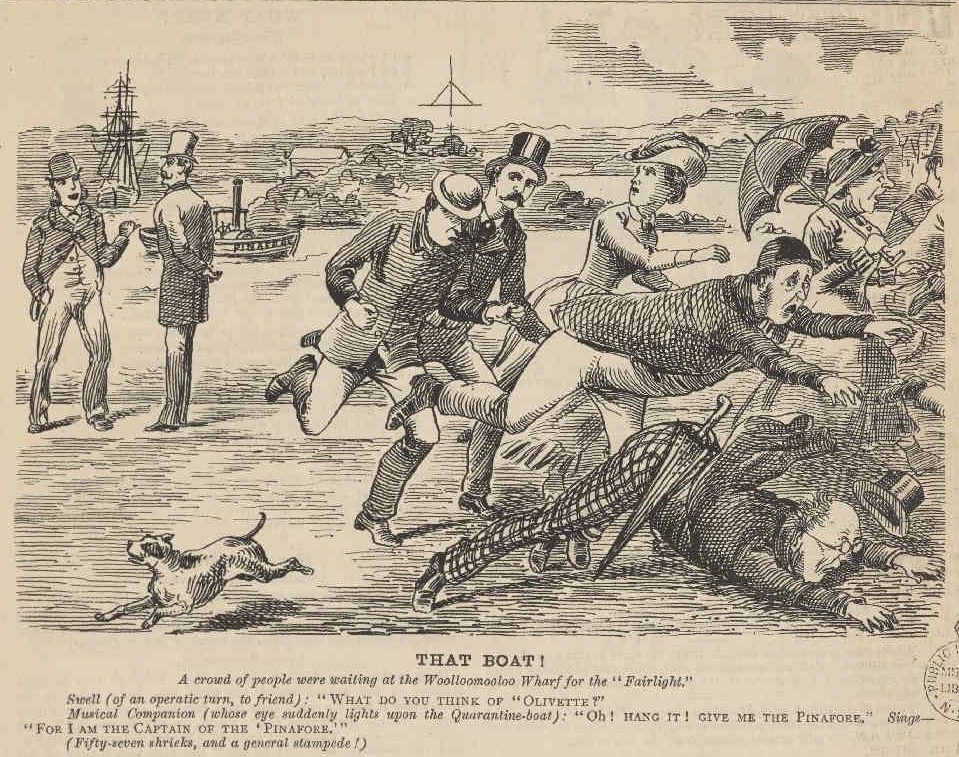

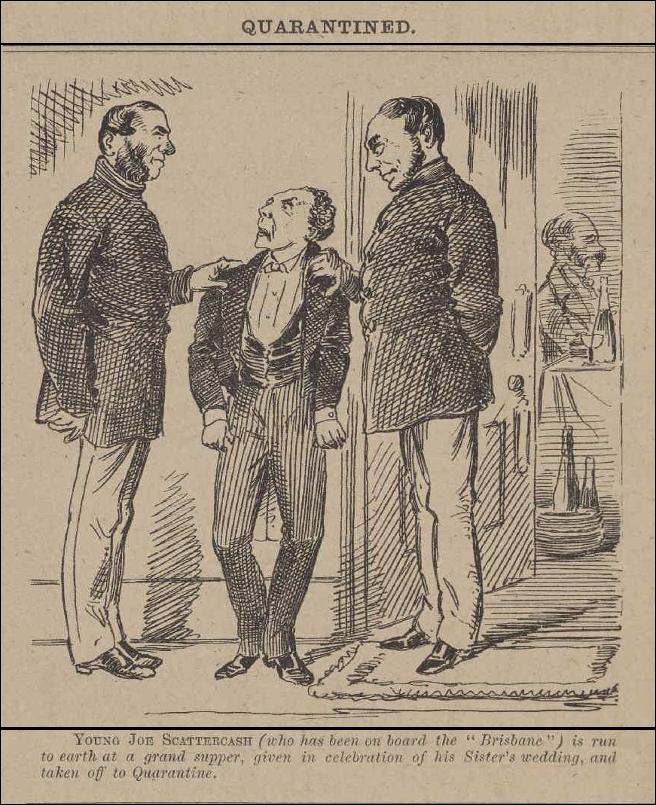

Young John Scattercash (who has been on board the “Brisbane”) is run to earth at a grand supper, given in celebration of his sister’s wedding, and taken off to quarantine.

(Sydney Punch, 1877)

(When Sir Arthur Kennedy, newly appointed as governor of Queensland, arrived on the steamer Brisbane from Hong Kong in March 1877, a “Chinaman” on board was found to be infected with smallpox. The ship and its hundreds of Chinese passengers were held in quarantine in Moreton Bay, but the political authorities dithered about whether Kennedy and his entourage should be exempted. A special medical commission was created to adjudicate, but this was widely dismissed as merely buying time to downplay a potentially unpopular decision that would be, at root, political. “The people of Australia are looked upon in England as being a trifle too democratic, as inclined to pay too little respect to high rank or exalted dignity,” proclaimed The Brisbane Courier. “It is reserved for the Imperial authorities to lower the state which has always been accorded to the Governor of Queensland, by sending us one, traveling to assume his Government, as a passenger on a merchant steamer crowded with hundreds of Chinese coolies… We have, however, a decided right to object to any relaxation of the precautions usually deemed necessary to prevent the landing of smallpox on our shores.” According to Krista Maglen, Australia favored quarantine as a tool of disease prevention well after Britain had abandoned this tactic, and not only for reasons of geographical isolation. This image makes clear the strong resonances with questions of class which quarantine also excited.)

Smith’s Weekly, Sydney, 1913

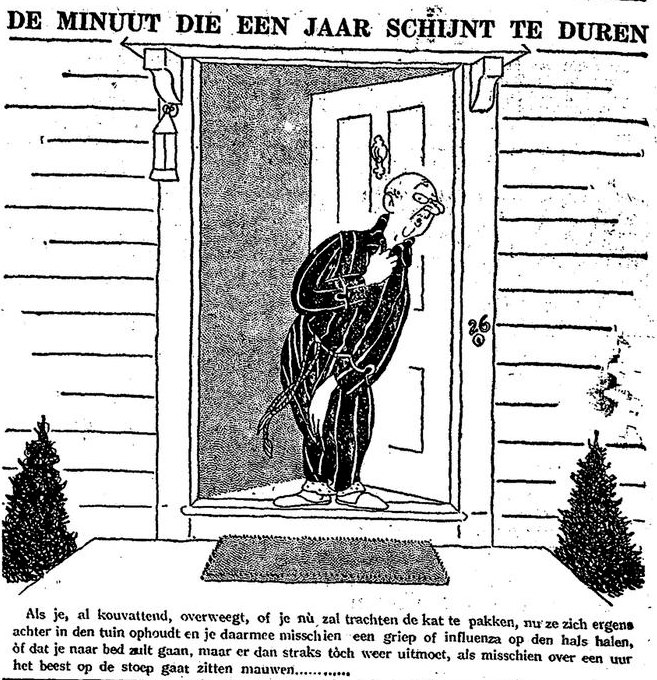

While catching a cold, you consider whether to try to catch the cat now, while she is hiding in the back of the garden and you might get a flu or influenza from it, or whether you will go to bed, but then have to go out there again later, when in an hour the beast will perhaps be meowing on the sidewalk ….

(Het Vaderland, ‘s Gravenhage, 1927)

Smith’s Weekly, Sydney, 1949

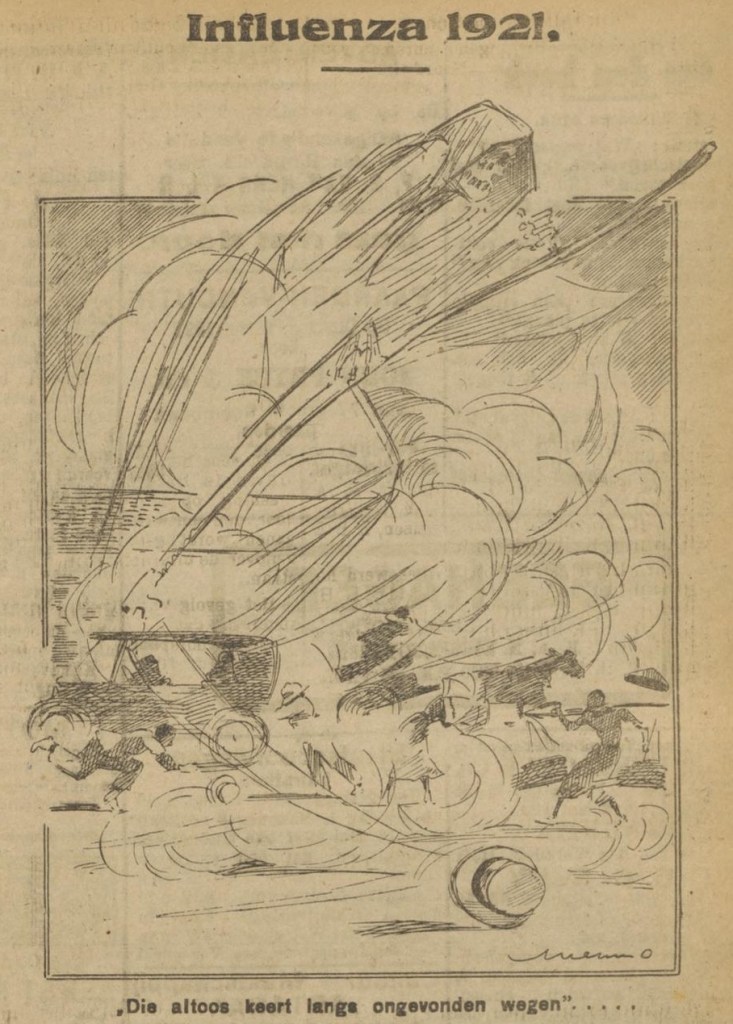

“It always proceeds along uninvited routes….”

(Het nieuws van den dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, 1921)

Smith’s Weekly, Sydney, 1933

Mother: “Child, why don’t I see your husband? He must be cured of the effects of influenza by now.”

Daughter: “There is still some shyness of humanity left.”

(Haagsche Courant, The Hague, 1895)