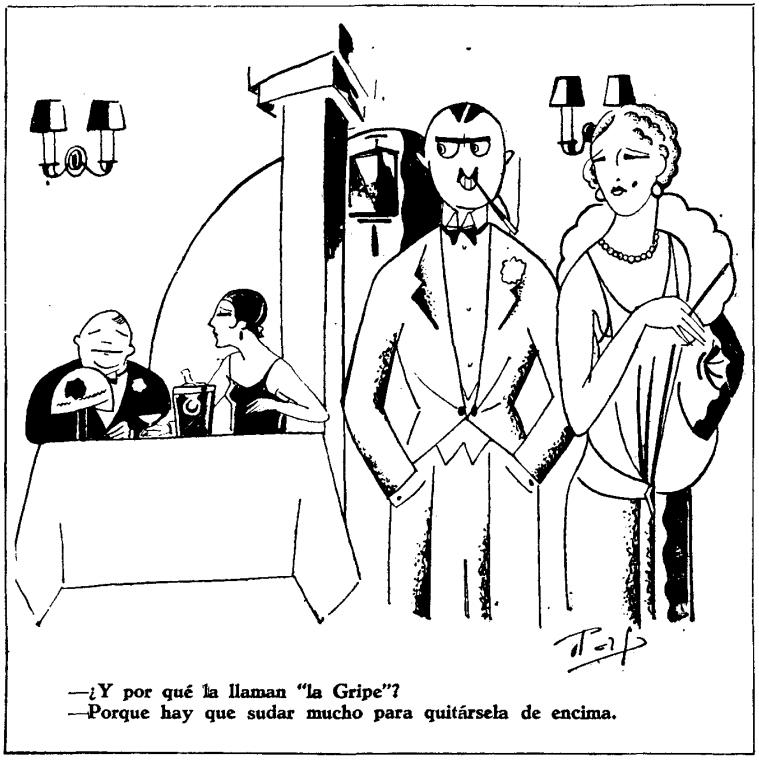

“And why do they call her “the Flu”?”

“Because you have to sweat a lot to get rid of her.”

(Gutiérrez, Madrid, 1931)

“And why do they call her “the Flu”?”

“Because you have to sweat a lot to get rid of her.”

(Gutiérrez, Madrid, 1931)

Whoever does nothing, sleeps; whoever sleeps, dreams; whoever dreams, is delirious; and… His Excellency has got “encephalitis lethargica.”

(O Malho, Rio de Janeiro, 1920)

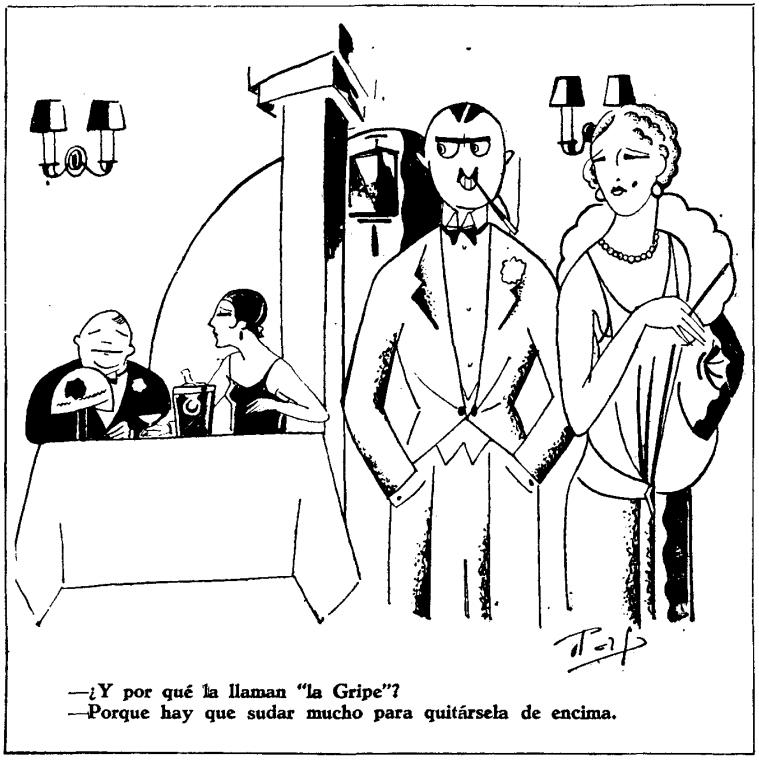

The speech of the English socialist Quelch at the International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart had an excellent effect. It prevented the outbreak of sleeping sickness among the members of the Hague Peace Conference.

(Der wahre Jacob, Berlin, 1907)

(Harry Quelch was famously expelled from Germany for referring to the Hague Peace Conference as a “thieves’ supper.”)

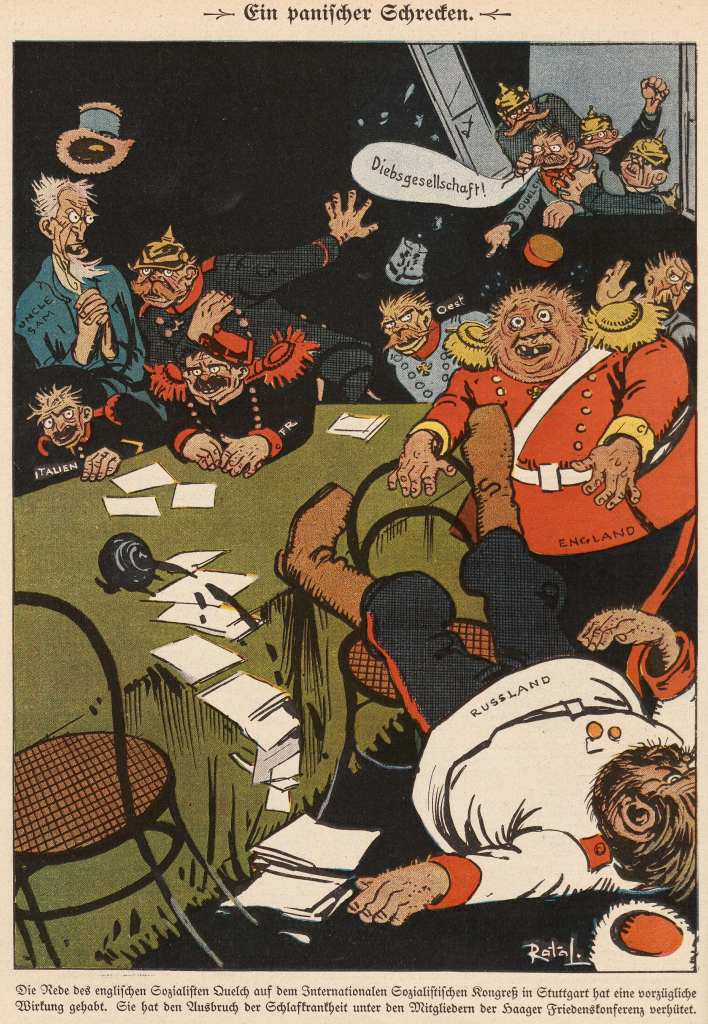

“Gentlemen! I begin today’s lecture on human illnesses.”

“If a person is sick, then Nature and illness are at odds with each other. The physician comes in and hits it with a club: if he hits the illness, then the person becomes healthy; but if he hits Nature, then the sick person dies.”

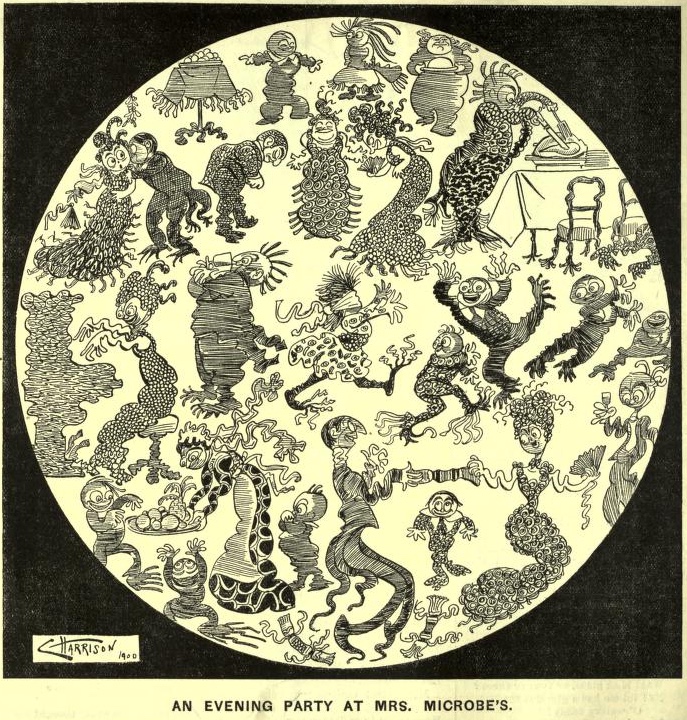

(Fliegende Blätter, Munich, 1847) (A British print in a similar vein.)

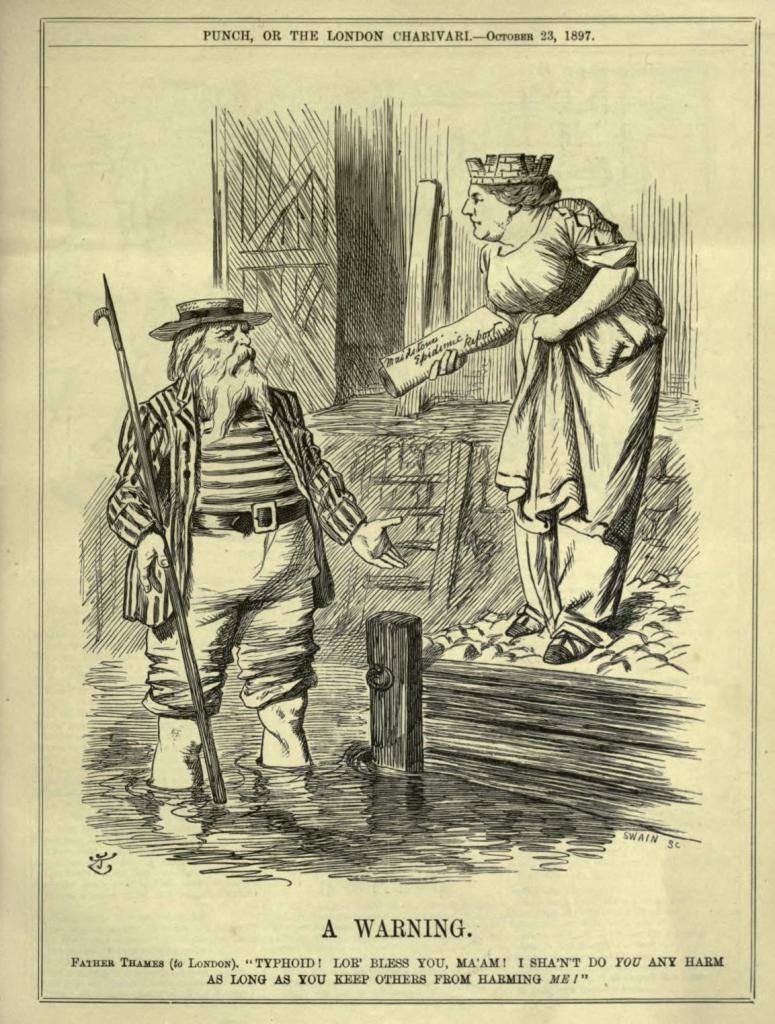

Father Thames (to London): “Typhoid! Lor’ bless you, ma’am! I shan’t do you any harm as long as you keep others from harming me!”

The Maidstone Epidemic Report in the hand of Lady London followed upon an outbreak of typhoid fever in Kent in September 1897 that eventually cost more than a hundred lives. The commission reporting on the causes of the epidemic found fault in the provision of water services by the Maidstone Company, in violation of the Public Health Act of 1878. The outbreak prompted an early successful experiment with immunization among nurses at a local hospital, according to this history.

(Punch, London, 1897)

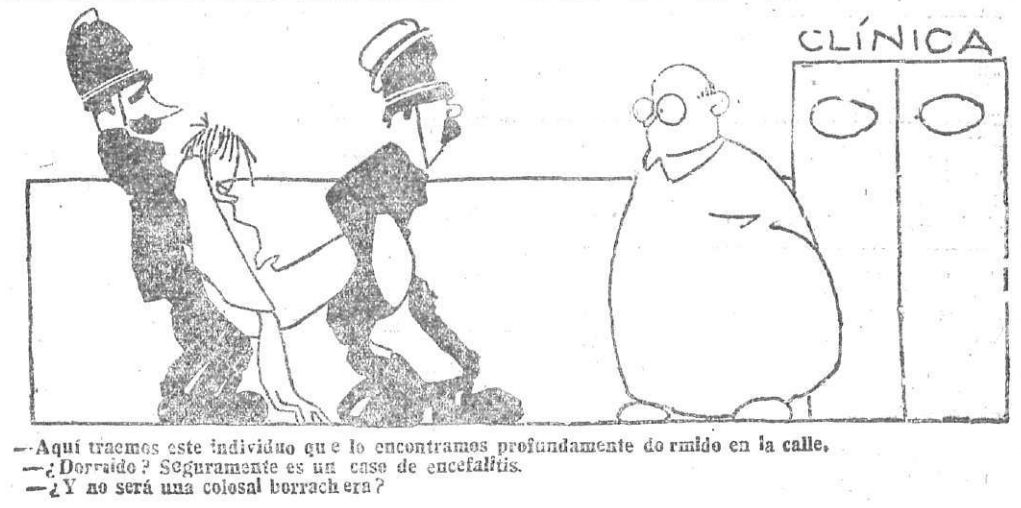

“Here we bring this individual that we found him sound asleep on the street.”

“Asleep? It is surely a case of encephalitis.”

“And it wouldn’t be a colossal drunk, would it?”

(El Mentidero, Madrid, 1920)

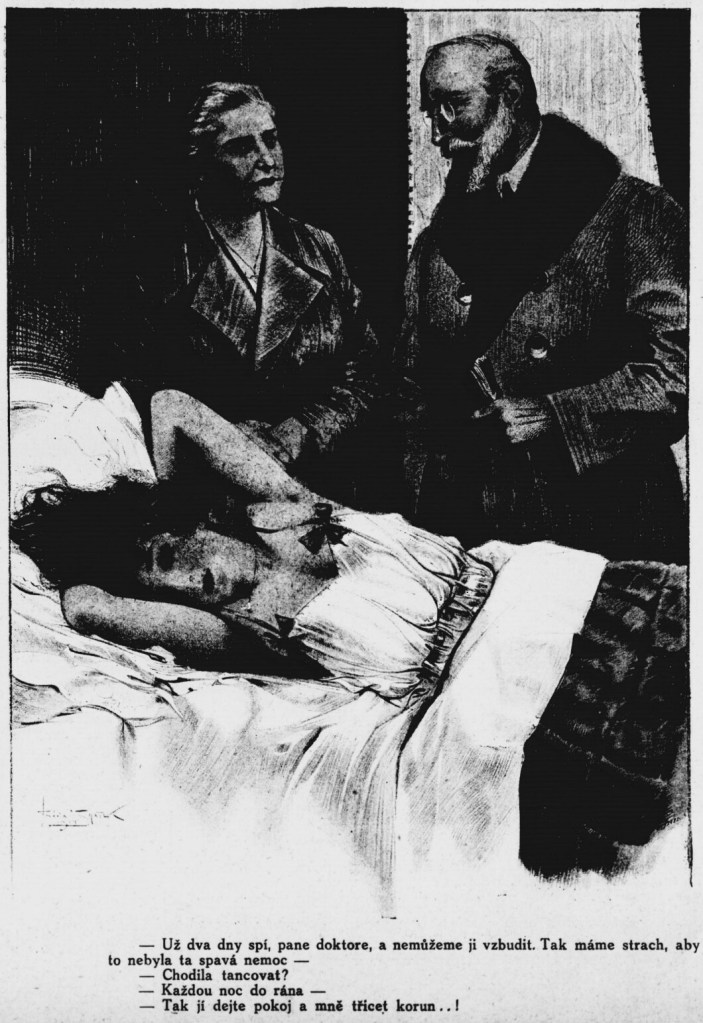

“She’s been sleeping for two days, Doctor, and we can’t wake her. So we’re afraid she’s got the sleeping sickness.”

“Has she been going dancing?”

“Every night until morning.”

“Then leave her alone and give me thirty crowns…!”

(Humoristické listy, Prague, 1924)

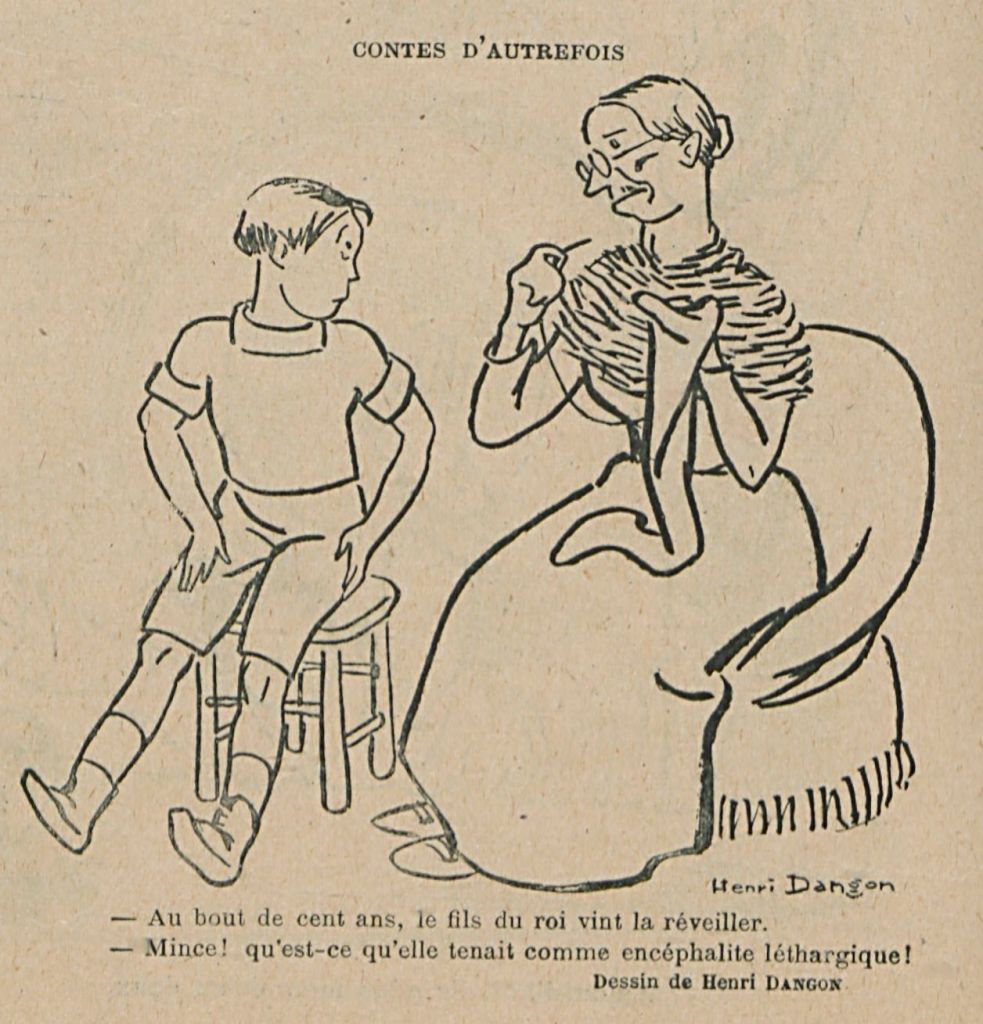

“At the end of a hundred years, the king’s son came to wake her up.”

“Darn! It’s like she had sleeping sickness!”

(Le Rire, Paris, 1920) (reproduced in Caras y Caretas)

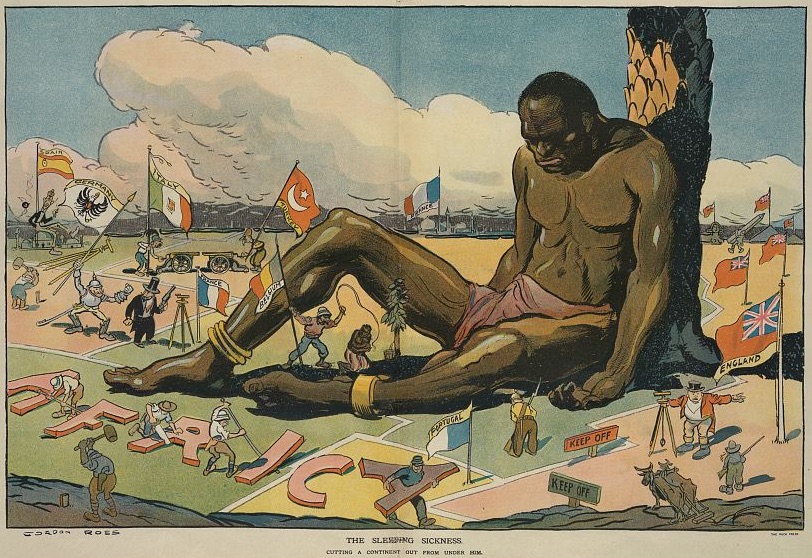

Cutting a continent out from under him.

(Puck, New York, 1911) (The cheapest of colonialist metaphors, and marginal to this archive’s concerns, but let us preserve it nonetheless.)

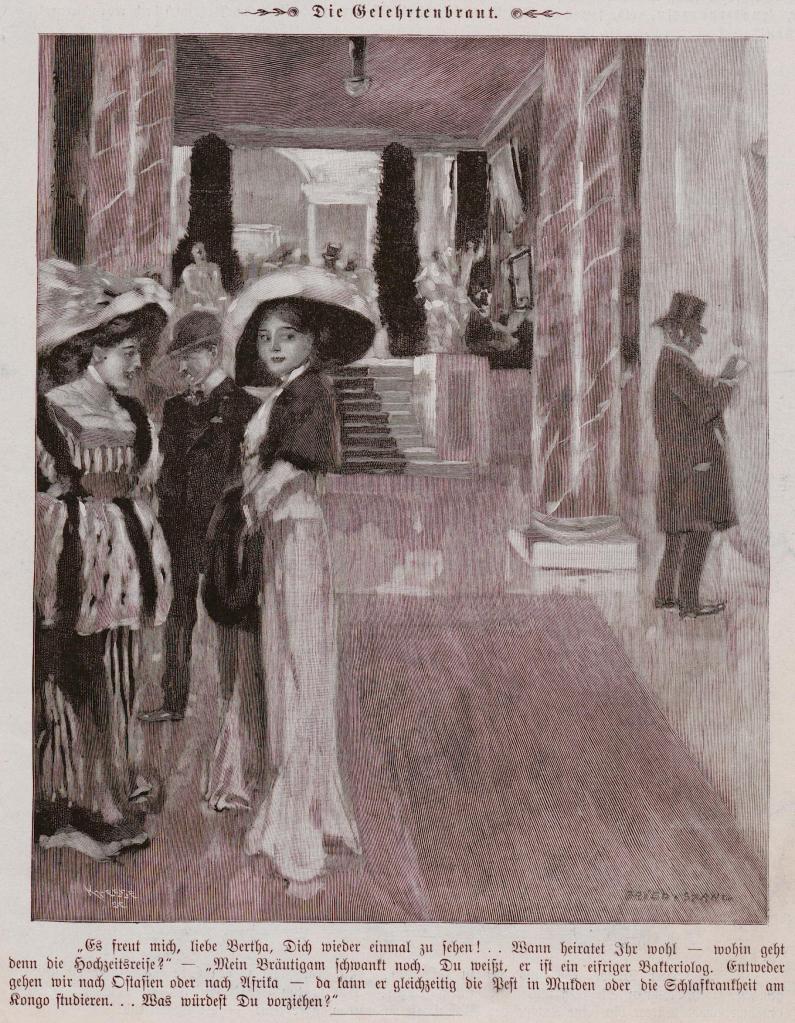

“I am so glad to see you again, dear Bertha!… When will you get married, where are you going for your honeymoon?”

“My bridegroom is still wavering. You know he’s an avid bacteriologist. We are going either to East Asia or to Africa. He can just as well study plague in Mukden or sleeping sickness in the Congo… Which would you prefer?”

(Fliegende Blätter, Munich, 1911) (See also this French version.)

(Punch, London, 1901)

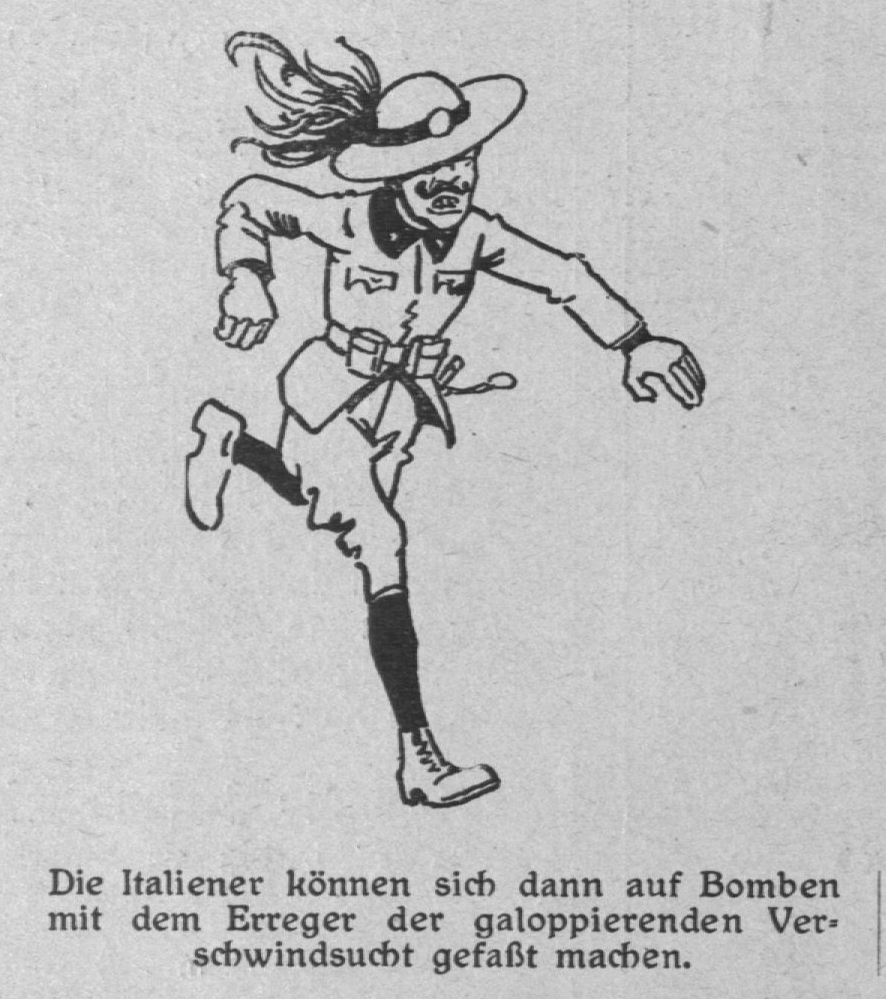

Main caption: A French man of culture has made the proposal to introduce bombs with plague bacteria as a new means of warfare. If this benevolent enterprise were to be realized, then the Central Powers will not be accountable for the reply.

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1915)

The Italians can then prepare themselves for bombs with the pathogen of galloping consumption.

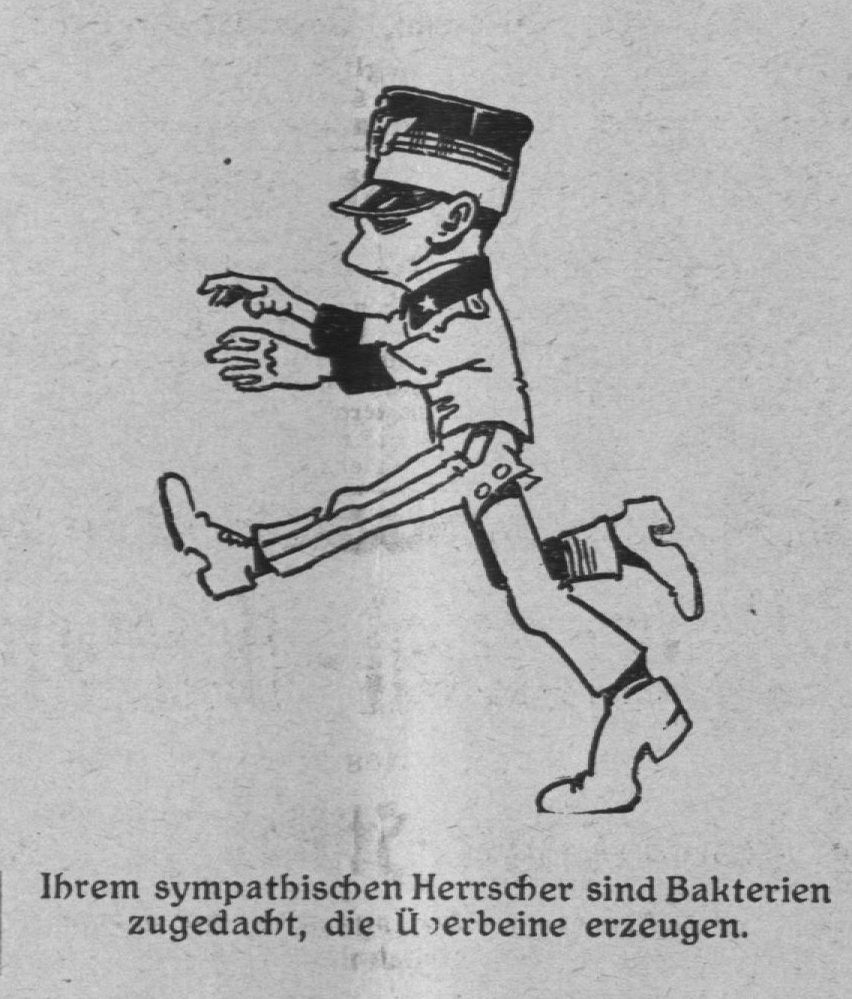

Bacteria which produce extra upper legs are intended for their sympathetic ruler.

For English listening posts bullets with the sleeping sickness pathogen are at the ready.

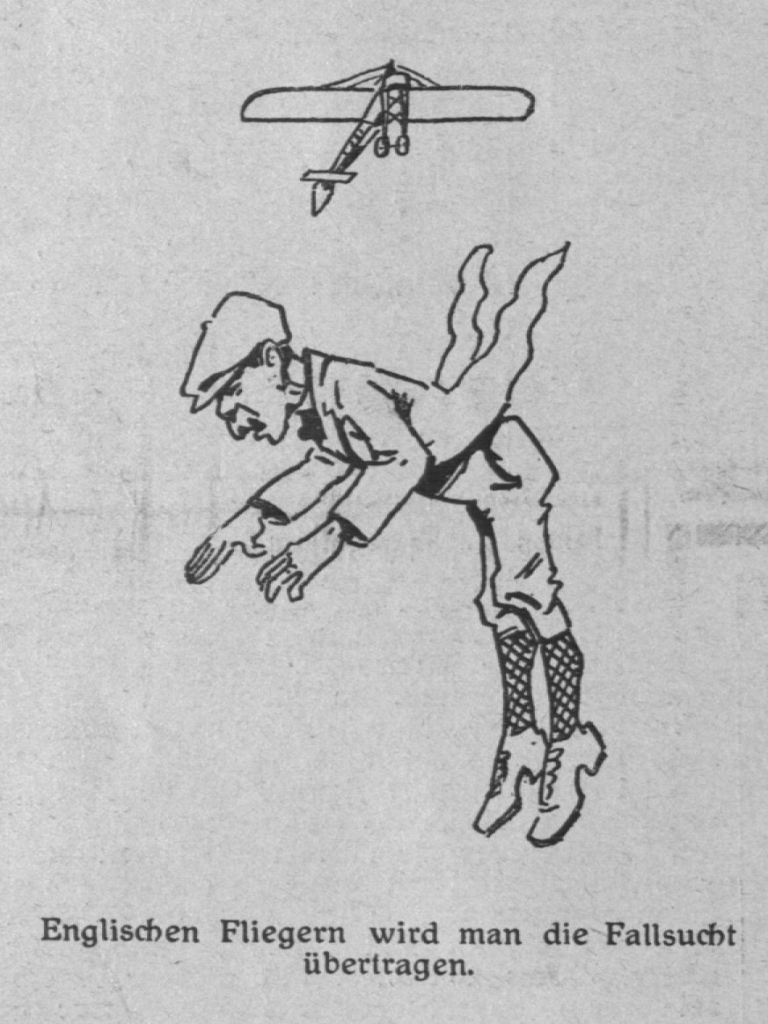

Epilepsy will be transmitted to English flyers.

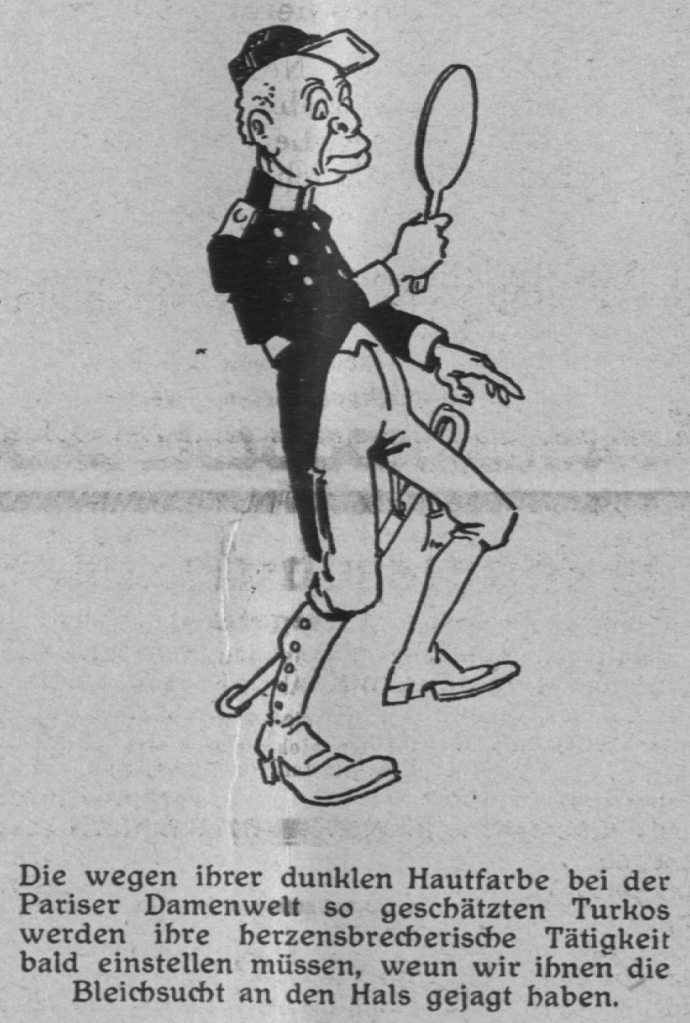

The Foreign Legion soldiers so valued by the Parisian ladies world for their dark skin color will have to cease their heartbreaking activity soon, when we’ve given them bleaching on their necks.

Transmitting the English disease to the equine ranks of the Allies is child’s play.

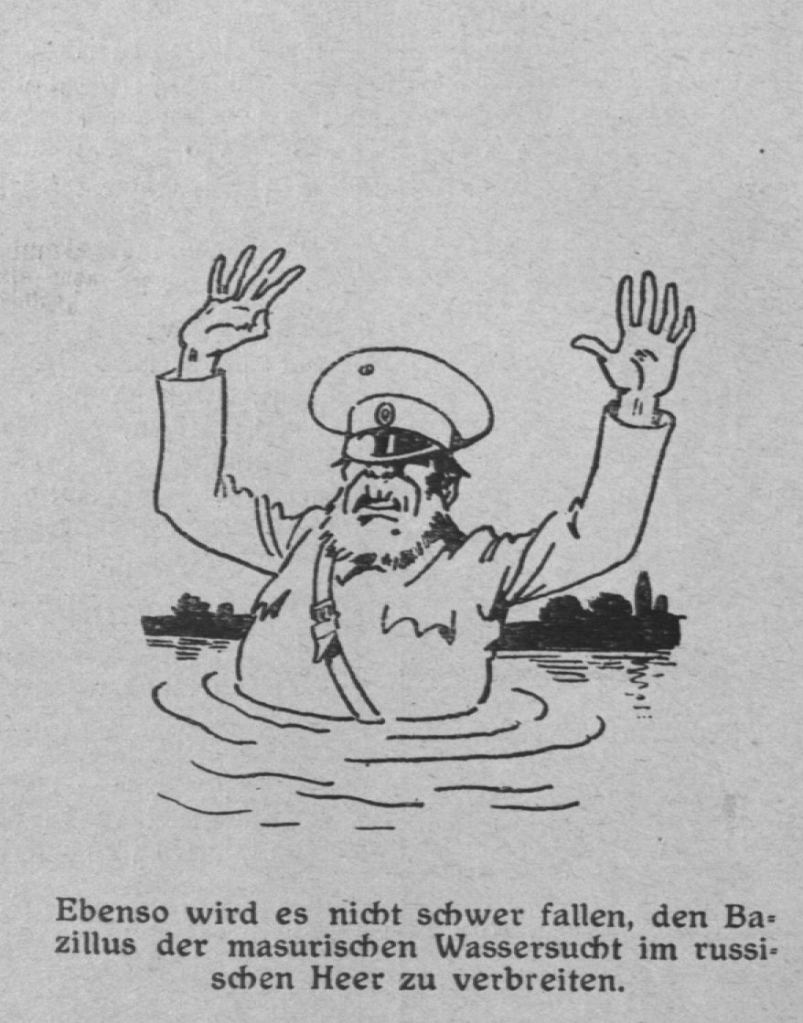

It will be just as easy to spread the bacillus of Masurian dropsy in the Russian army.

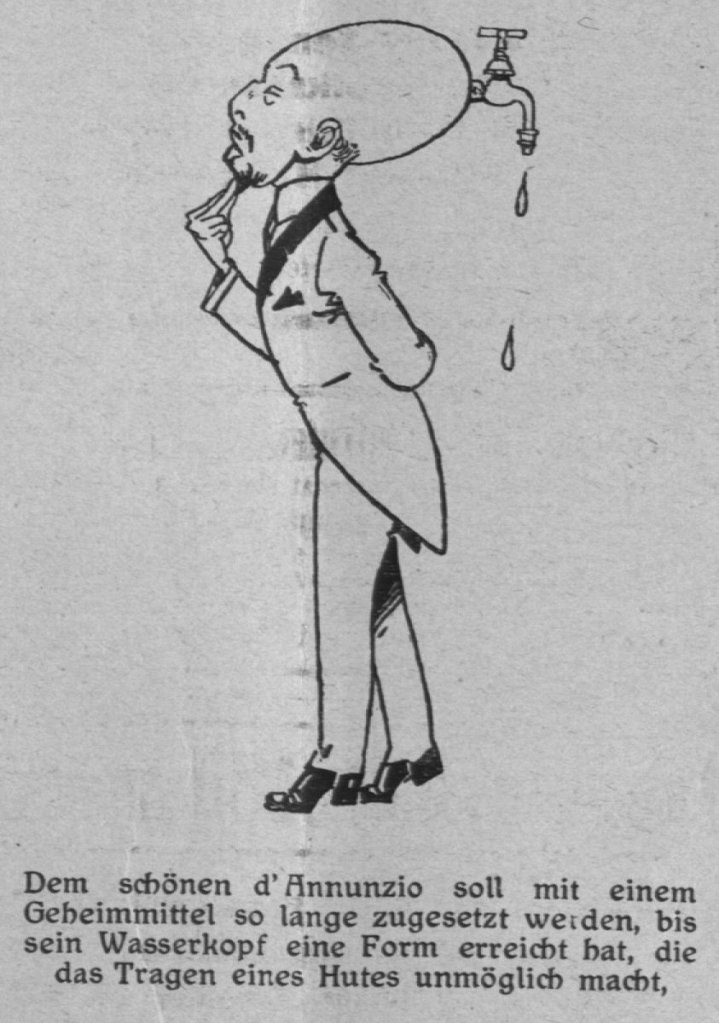

The lovely d’Annunzio ought to be punished by a secret medicament until his hydrocephaly has attained a form that makes it impossible to wear a hat.

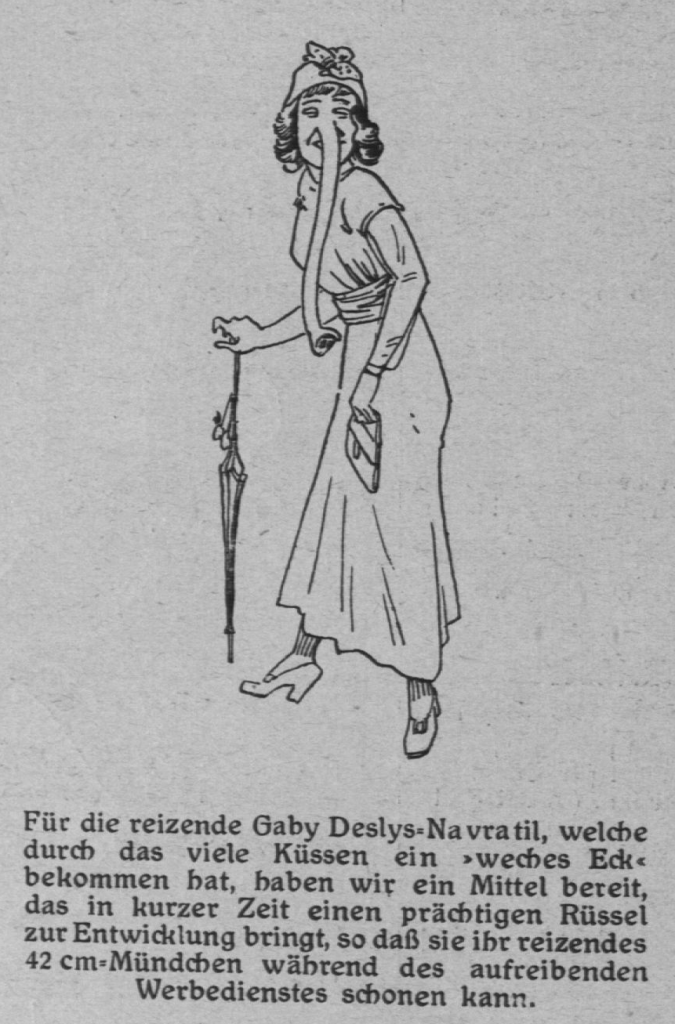

For the delightful Gaby Deslys-Navratil [an immensely popular French singer and silent film actor who would expire in 1920 from complications following a bout with Spanish flu], who has gotten into a bit of a spot from all the kissing, we have a means ready to develop a splendid trunk in a short time, so that she can spare her lovely 42 cm mouth during her grueling advertising service.

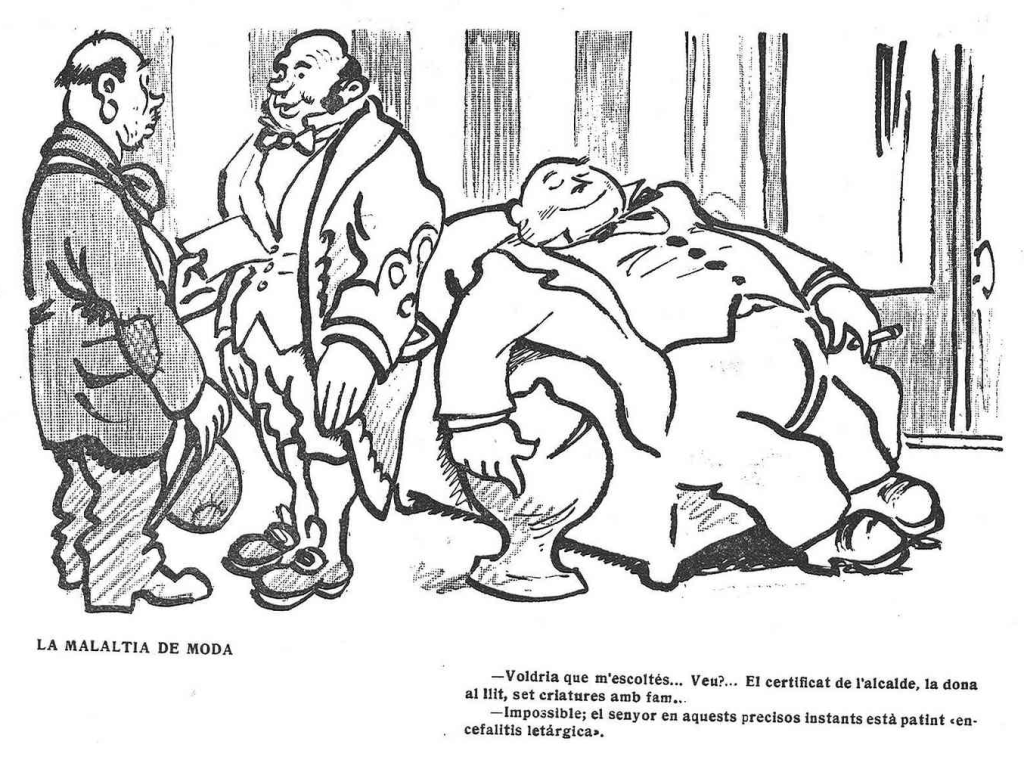

“Would you please hear me out… Voice?… The mayor’s certificate, the lady of the house in bed, with seven hungry children…”

“Impossible; the gentleman is currently suffering from ‘encephalitis lethargica’ [sometimes called sleeping sickness].”

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1920)

Doctor: “Don’t be alarmed. Your husband’s illness is not serious; however, you have to be very careful. Any disorder, a strong sensation, a violent emotion, can be fatal…”

(second panel) The emotion!

(La Risa, Madrid, 1922)