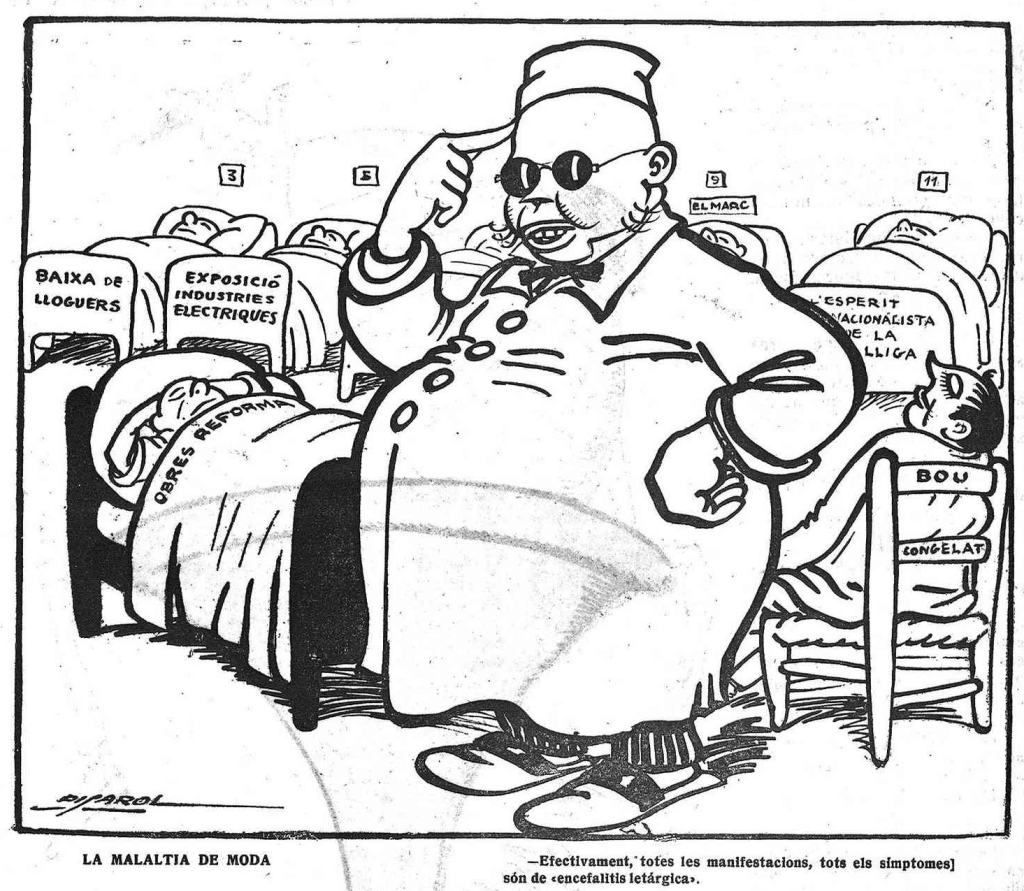

(Suffering patients include low rents, renovation works, the nationalist spirit of the league, frozen beef (?).)

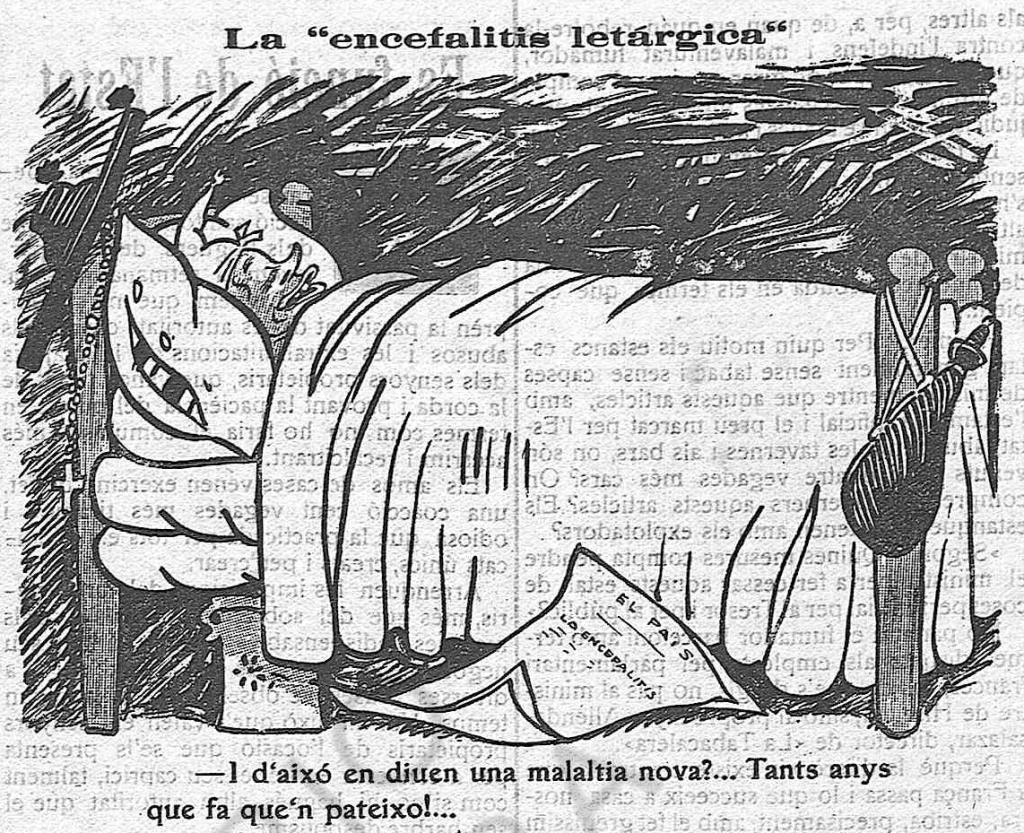

“Indeed, all the manifestations, all the symptoms are of the ‘encephalitis lethargica’.”

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1920)

(Suffering patients include low rents, renovation works, the nationalist spirit of the league, frozen beef (?).)

“Indeed, all the manifestations, all the symptoms are of the ‘encephalitis lethargica’.”

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1920)

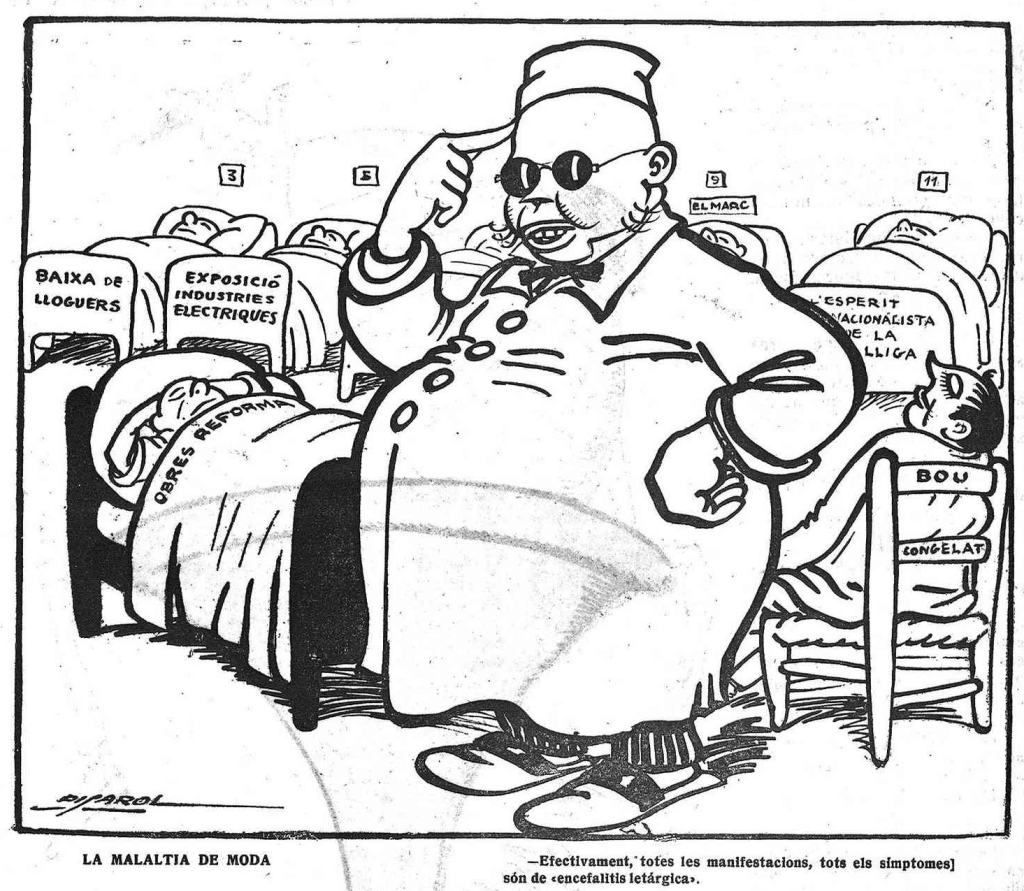

“The compensations aren’t that bad; the Congo Colony is indeed extremely valuable to us: you can send the socialists there if they get too lively, so that they get sleeping sickness!”

(Der wahre Jacob, Stuttgart, 1911)

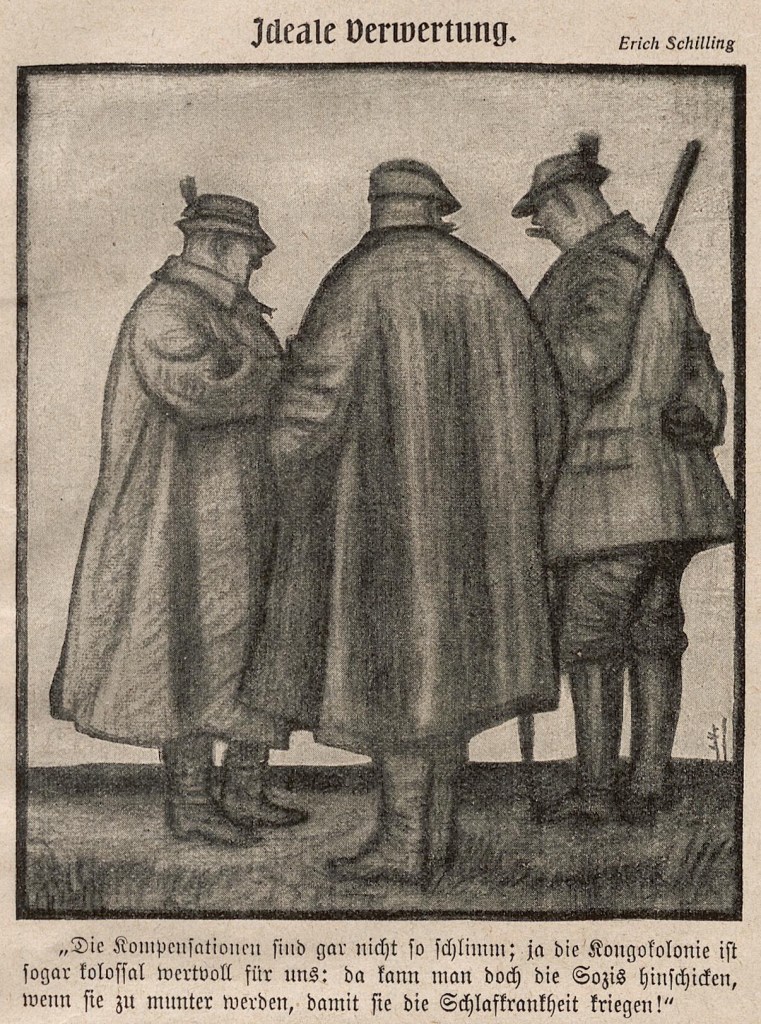

Professor Koch has discovered an extremely effectively treatment against sleeping sickness. (Namely, loudly advertising his colonial researches.)

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1907)

(In 1906 the famous German bacteriologist Robert Koch led a group of researchers to German East Africa in search of a cure for African sleeping sickness. Experimenting with a “magic bullet” of the sort his protégé Paul Ehrlich had developed in his laboratory, Koch and his associates treated thousands of patients with Atoxyl, an arsenic-based substance with toxic side effects. Though Koch remained convinced of its efficacy up to his death in 1910, this therapy proved to be his greatest failure.)

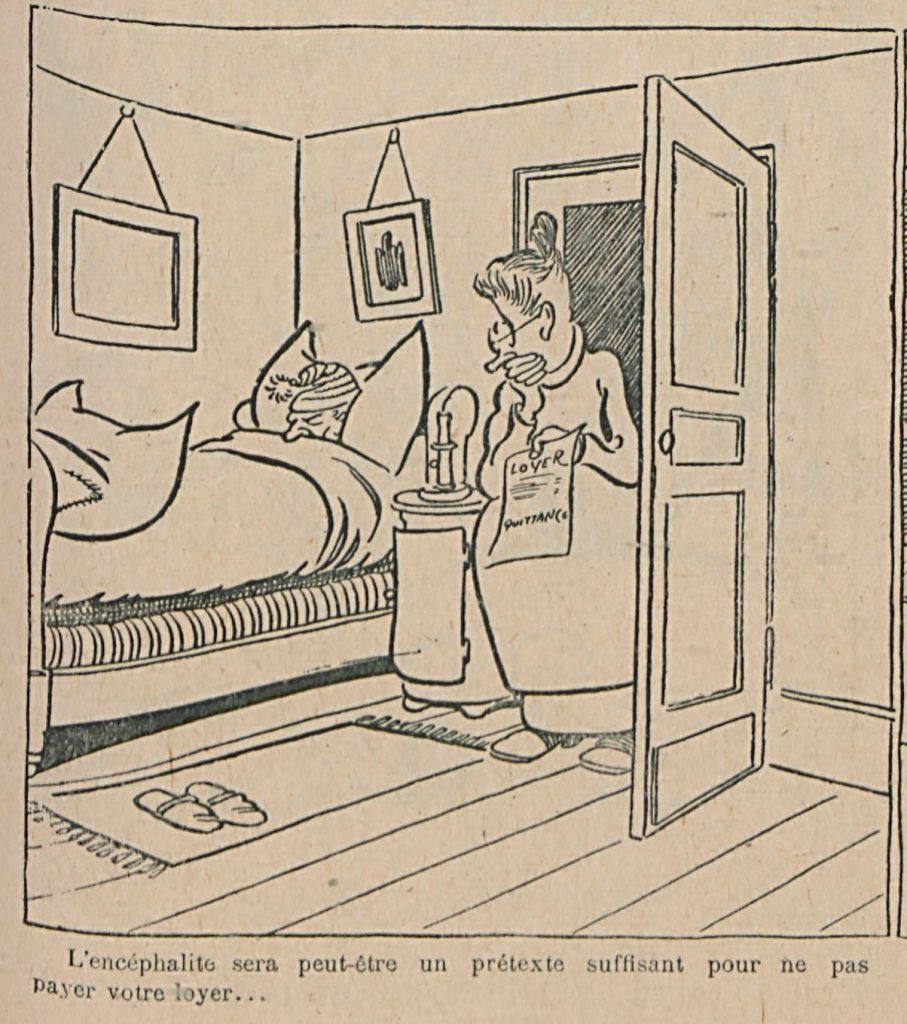

“Encephalitis might be a sufficient pretext for not paying your rent…”

(Le Rire, Paris, 1920)

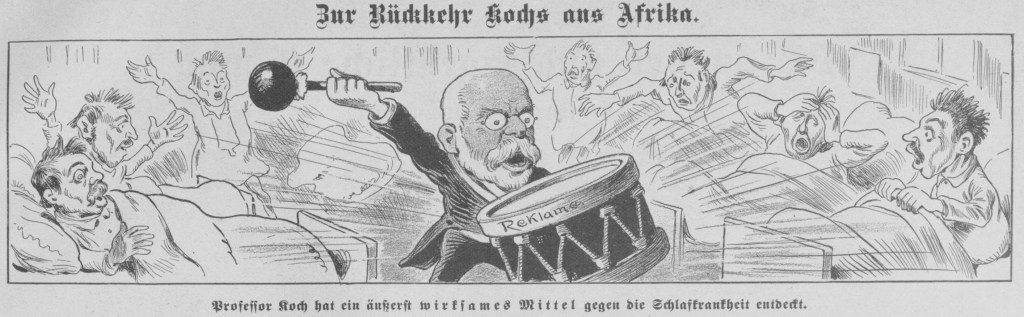

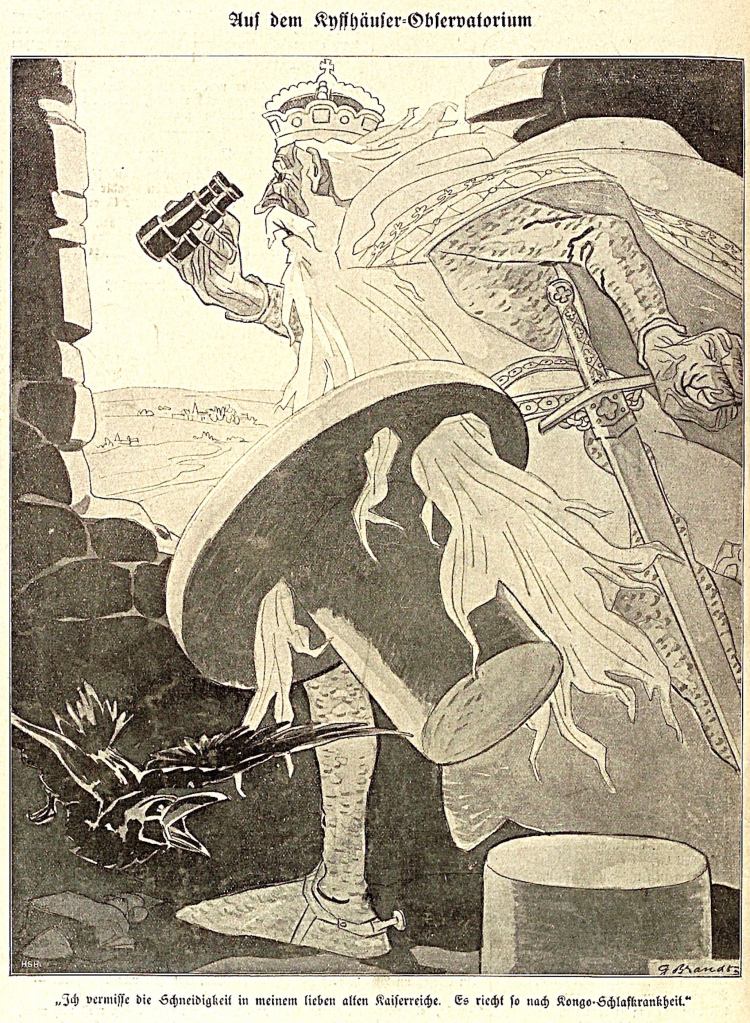

At Kyffhäuser on the northern border of Thuringia in Germany lies a giant modern monument to the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I (“Barbarossa”), also the site of an ancient astronomical observatory. This image was published more or less at the height of the Second Reich’s modest colonial ventures in Africa.

“I miss the edginess in my dear old empire. It smells so much like Congo sleeping sickness.”

(Kladderadatsch, Berlin, 1911)

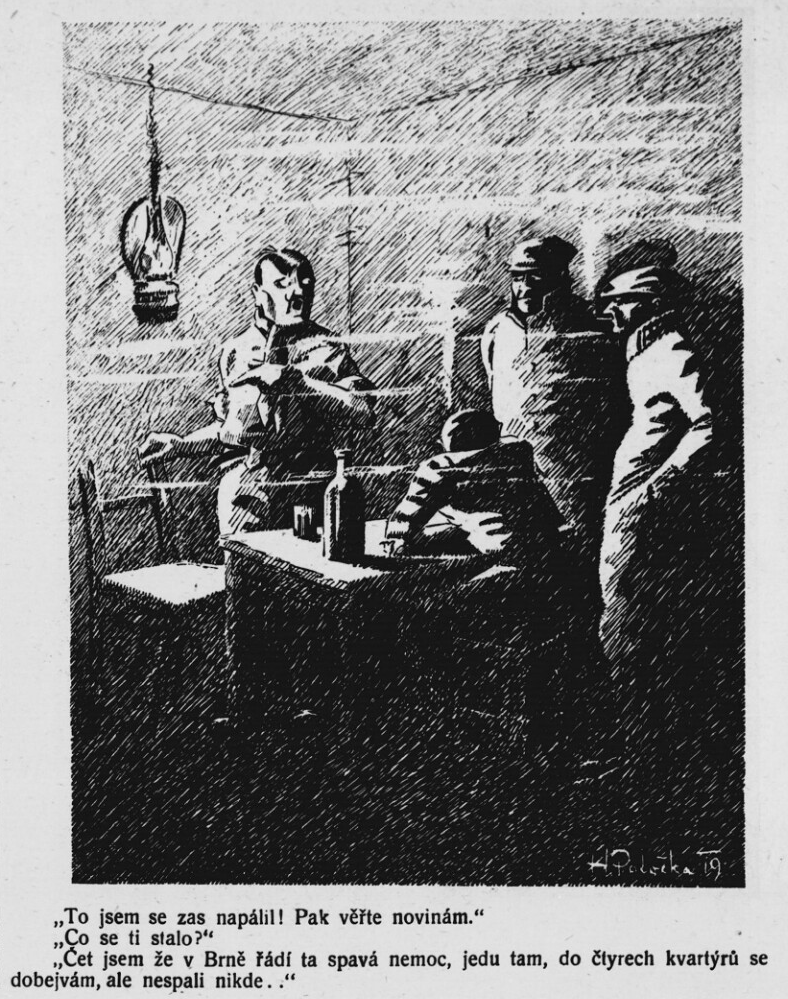

“I fooled myself again. Then you should trust the news.”

“What happened?”

“I read that the sleeping sickness is raging in Brno, I head there, I get into four apartments, but nobody was sleeping anywhere…”

(Humoristické listy, Prague, 1920)

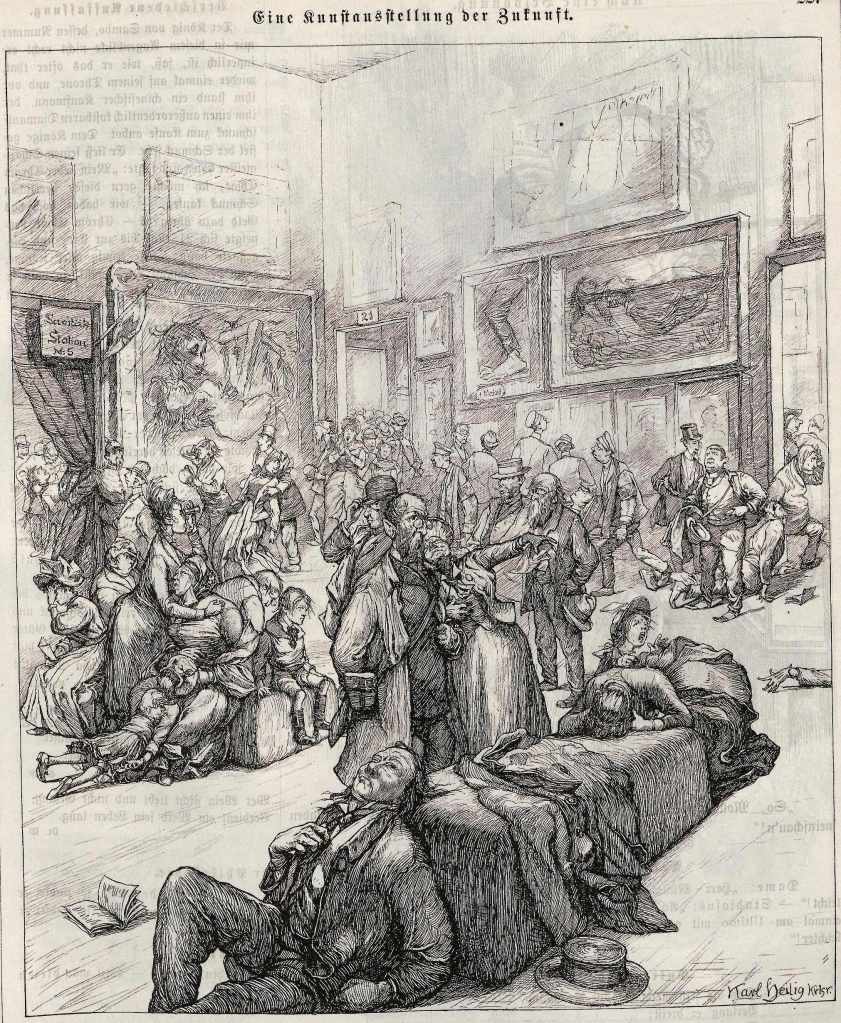

(With a flu epidemic underway late in 1889, this image signaled the duress not only in the grim artworks on the walls and the ailing visitors sprawled around the exhibition space. On the left one can see a sign for “Hygiene Station No. 5,” a deft reminder of our present dilemmas.)

(Fliegende Blätter, Munich, 1889)

“It seems that a sleeping sickness epidemic is raging in America… the business of economic recovery has also fallen asleep.”

(Az Ojság, Budapest, 1933)

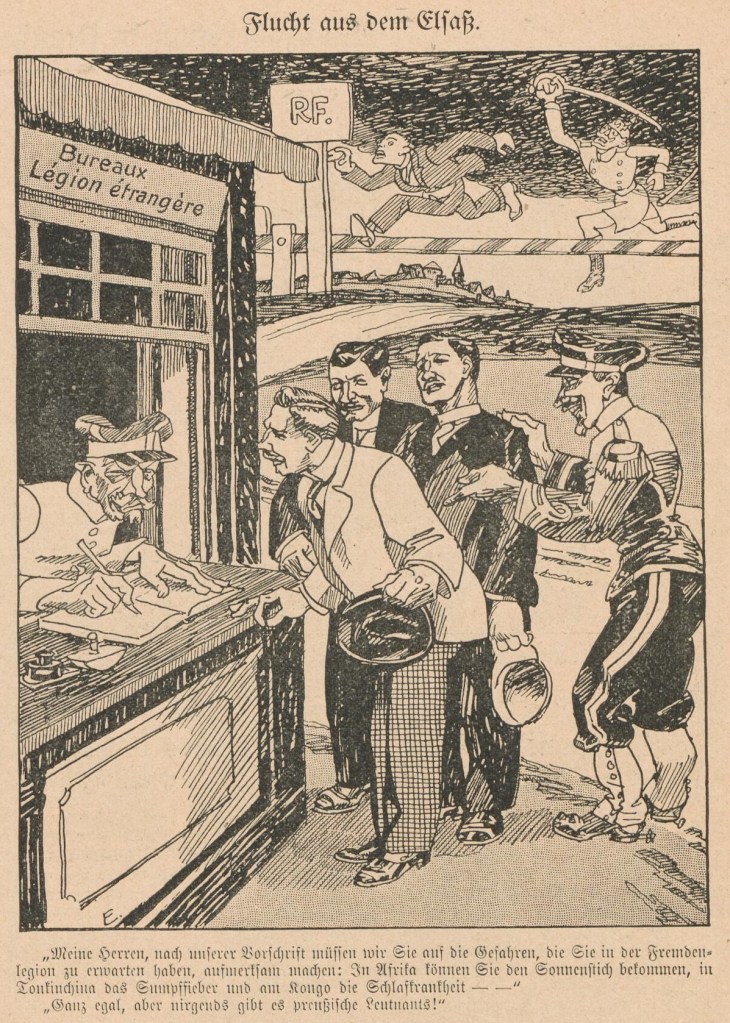

(At the French Foreign Legion Offices)

“Messieurs, according to our rules, we must draw your attention to the dangers that you can expect in the Foreign Legion: you can get sunstroke in Africa, malaria in Tonkin China, and sleeping sickness in the Congo…”

“It doesn’t matter, just so there are no Prussian lieutenants anywhere!”

(Der wahre Jacob, Stuttgart, 1914)

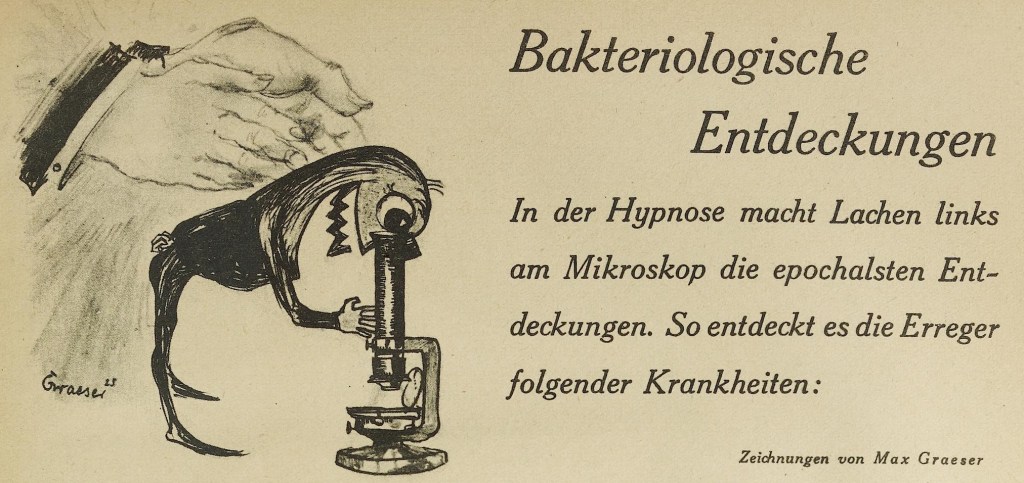

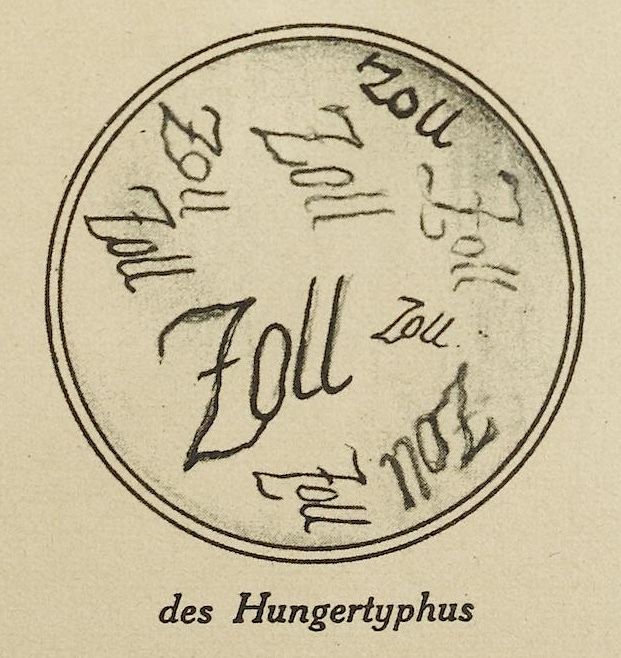

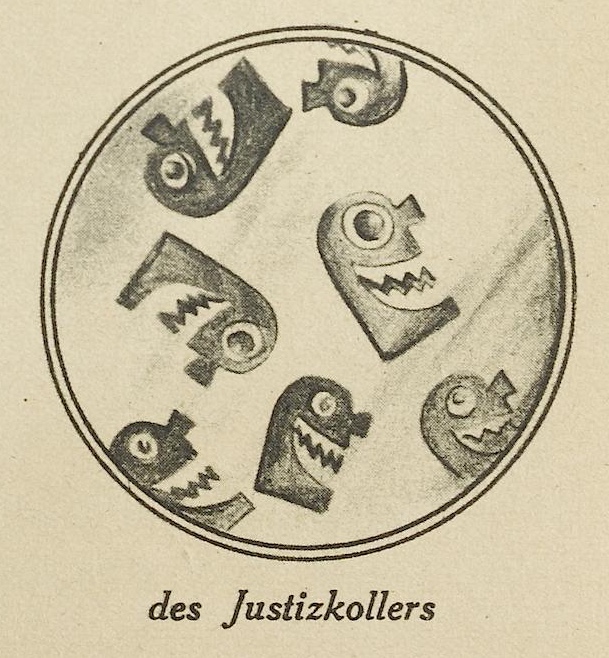

In hypnosis Lachen links [~ “laughing on the left”] is making the most epochal discoveries. Thus the pathogens of the following illnesses are discovered:

Nine panels follow, of which I include three here. Sleeping sickness:

Hunger typhus [“tariff” vibrios]:

Judicial cholera:

(Lachen links, Berlin, 1926)

“Is this what they call a new disease?… I’ve been suffering from it for so many years!…”

(La Campana de Gracia, Barcelona, 1920)

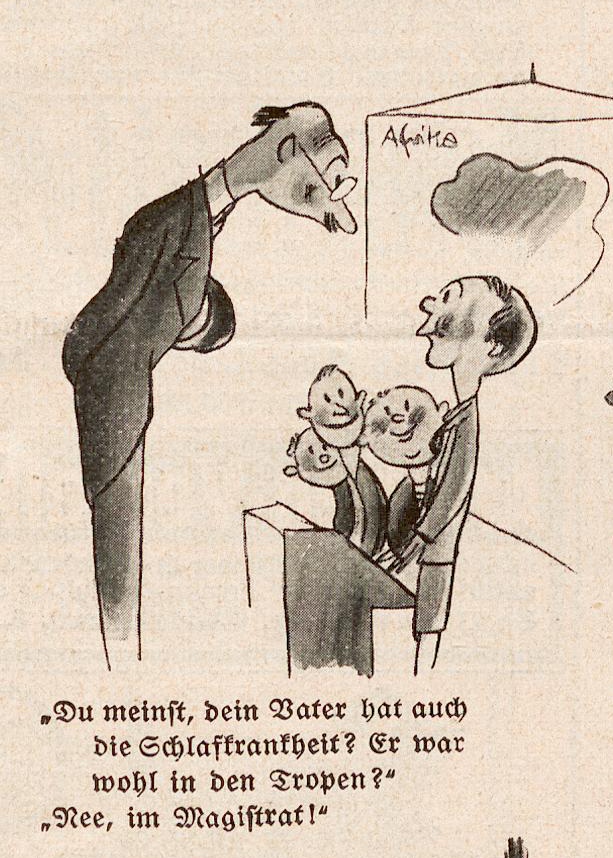

“You mean your father has sleeping sickness, too? Was he in the tropics?”

“Nope, at the municipal authorities!”

(Fliegende Blätter, Munich, 1929)

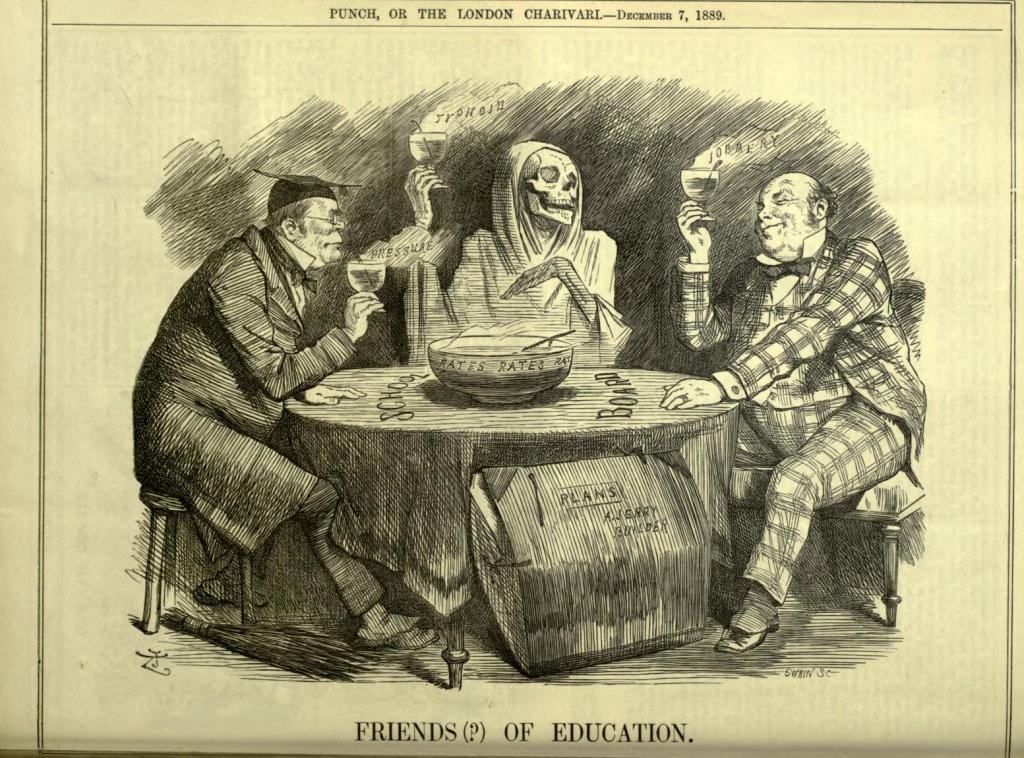

Pressure, typhoid fever, and jobbery as members of the school board. I haven’t looked into the politics referenced here, but I include this image because of its seeming resonances with our own current imperatives, trying to reconcile in-person instruction with the real-world behaviors of students in epidemic conditions.

(Punch, London, 1889)

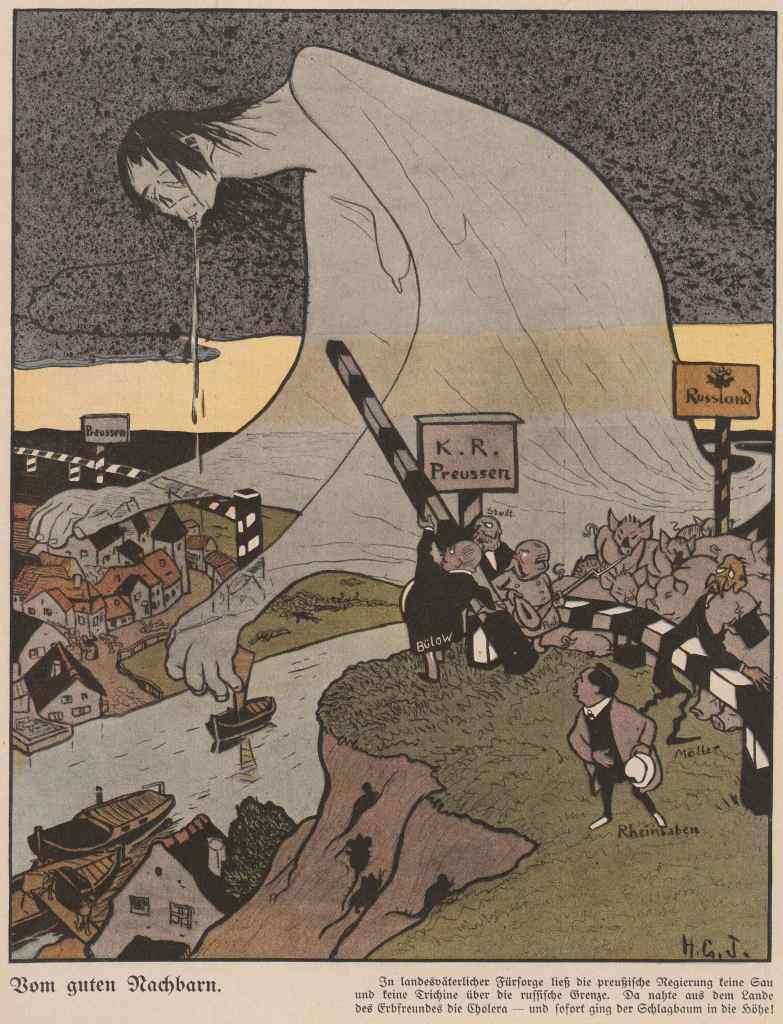

Out of paternal concern for the country, the Prussian government did not let swine and trichina across the Russian border. Then cholera was approaching from the land of the hereditary friend — and immediately the barrier was lifted!

(Der wahre Jacob, Stuttgart, 1905) (With thanks to Alexander Maxwell.)

Lady: “You are eating cucumber salad and drank your beer first; I wouldn’t do that here where we have the cholera!”

Gentleman: “I am only staying here for my pleasure, I’m not from here.”

(Fliegende Blätter, Munich, 1866)