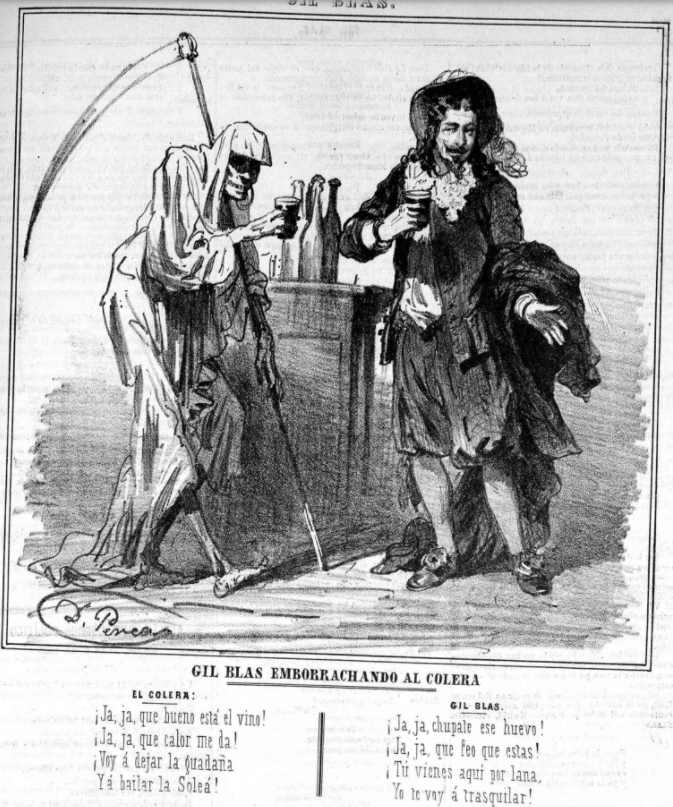

Cholera:

Ha ha, how good is the wine!

Ha ha, how hot it makes me!

I will leave the scythe

And dance the flamenco!

Gil Blas:

Ha ha, suck that egg!

Ha ha, how ugly you are!

You come here for wool,

I’m going to shear you!

(Gil Blas, Madrid, 1865)

Cholera:

Ha ha, how good is the wine!

Ha ha, how hot it makes me!

I will leave the scythe

And dance the flamenco!

Gil Blas:

Ha ha, suck that egg!

Ha ha, how ugly you are!

You come here for wool,

I’m going to shear you!

(Gil Blas, Madrid, 1865)

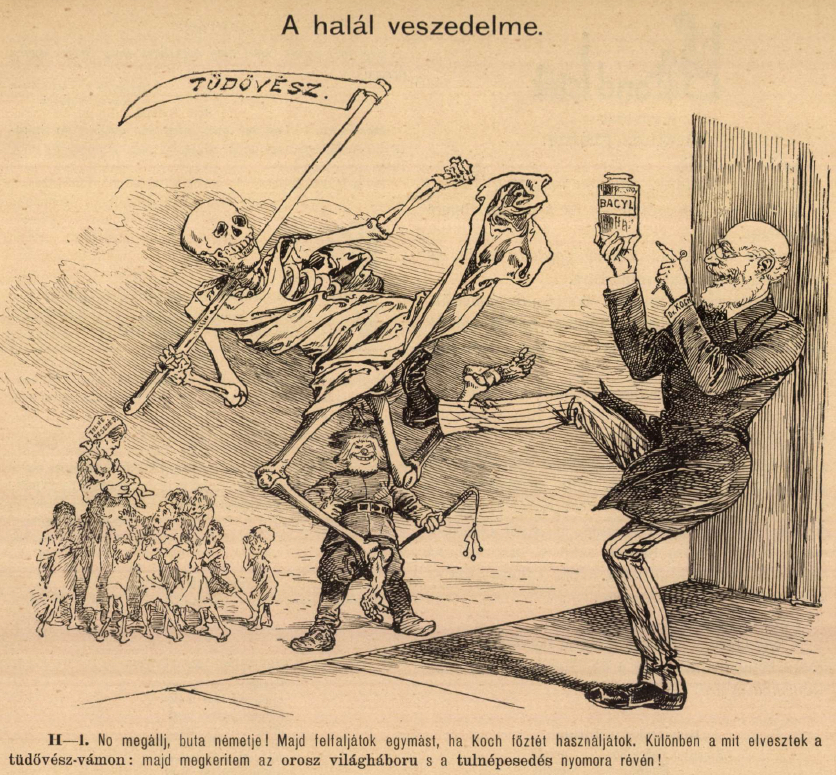

Death: “Well, stop it, silly German! You’re about to devour each other if you use Robert Koch’s concoction. Anyway, whatever I lost in my tuberculosis tariff, I will get hold of through the misery of the Russian world war and overpopulation!” (A reference to the Russian repudiation of alliances with Germany and Austro-Hungary in favor of France, its failed politics in the Balkans, and renewed tensions with imperial Britain in Central Asia.)

(Bolond Istók, Budapest, 1890)

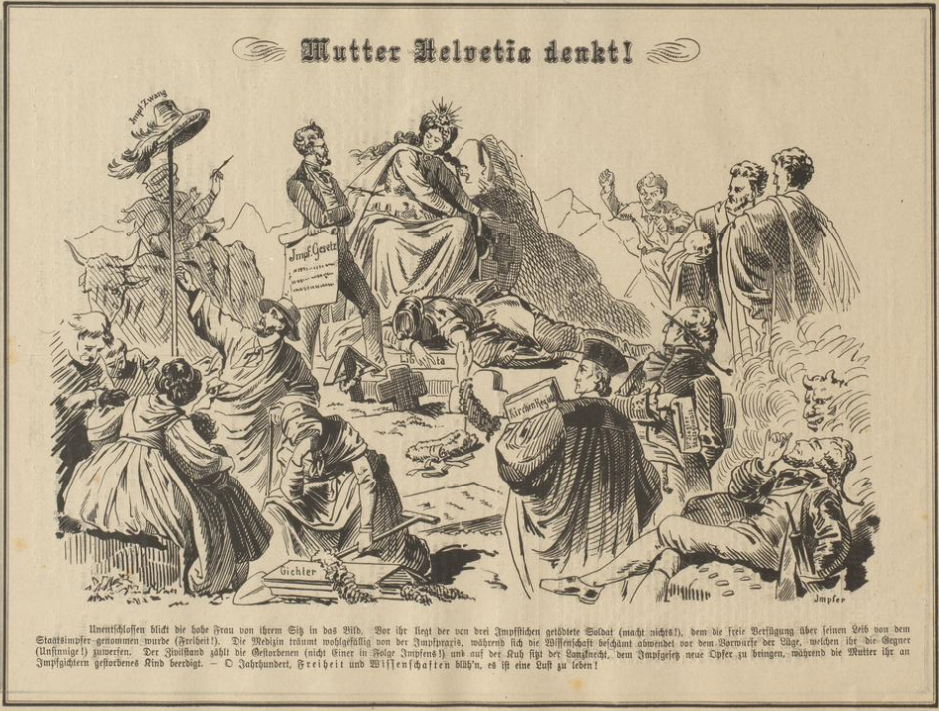

(The fancy hat at upper left is labeled “obligatory vaccination.” The gentleman standing before Mother Helvetia carries the vaccination law.)

In the picture the grand lady peers indecisively from her seat. Before her lie three soldiers dead from vaccination (don’t do it!), men whose bodies had been given over to the free disposal of the city vaccinator (freedom!). Medicine dreams pleasantly of vaccination practice, while science turns away in shame from the accusation of lying which the opponents (nonsensical!) lodge at her. The citizens count the deceased (more than one as a result of vaccination!) and on the cow sits the lanceman [administering the knick of inoculation] making new sacrifices to the vaccination law, while the mother buries her child who died from a bad inoculation batch. “O century, freedom and science flourish, it is a pleasure to live!” (Evoking the great Reformation thinker Erasmus.)

(Nebelspalter, Zurich, 1882)

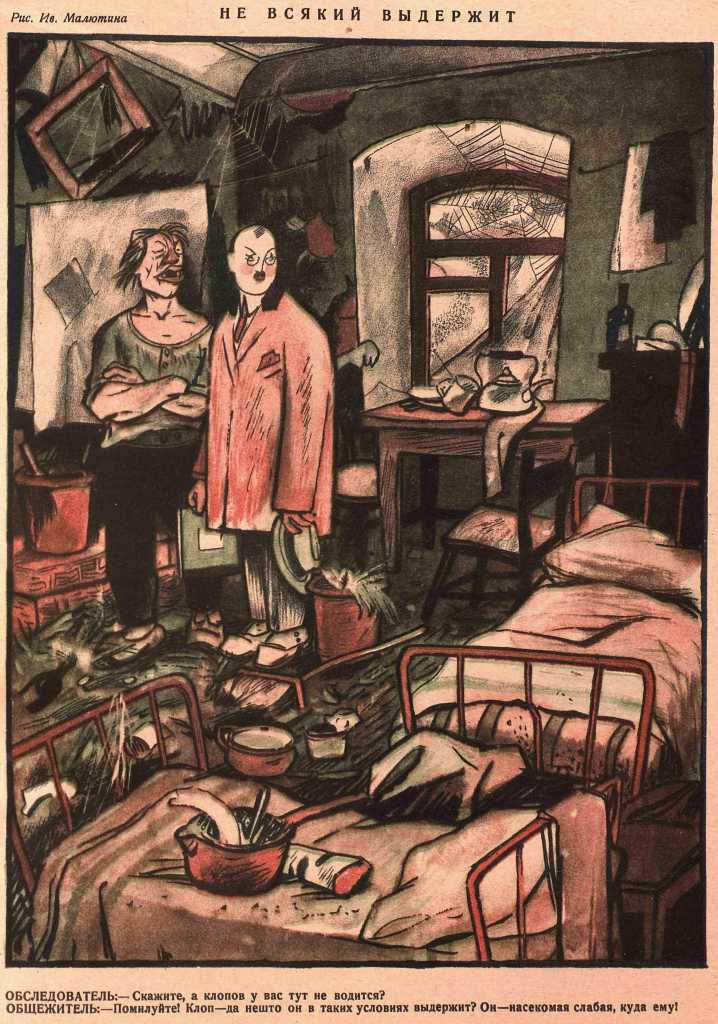

Inspector: “Say, are there any bedbugs found here?”

Resident: “Mercy! Can bedbugs stand these conditions? It’s a weak insect, where would it go?”

(Krokodil, Moscow, 1927)

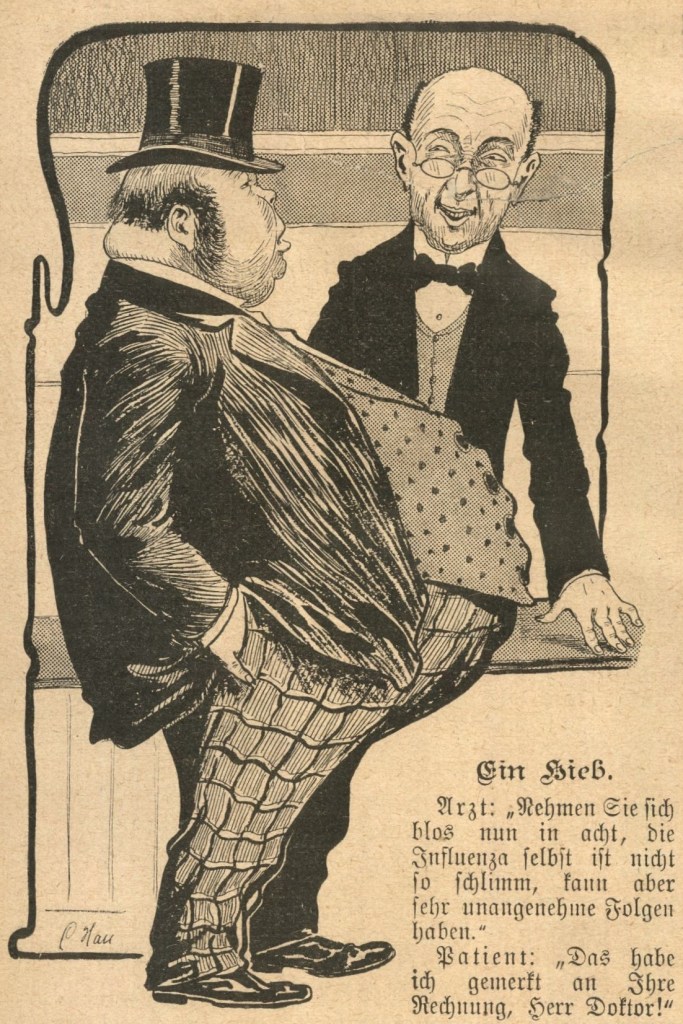

Physician: “Keep in mind that the influenza is itself not so bad, but it can have very unpleasant aftereffects.”

Patient: “I noticed that when I got your bill, Doctor!”

(Humor/Neues Wiener Journal, Vienna, 1900)

A nearly identical cartoon in Der Floh, Vienna, 1899:

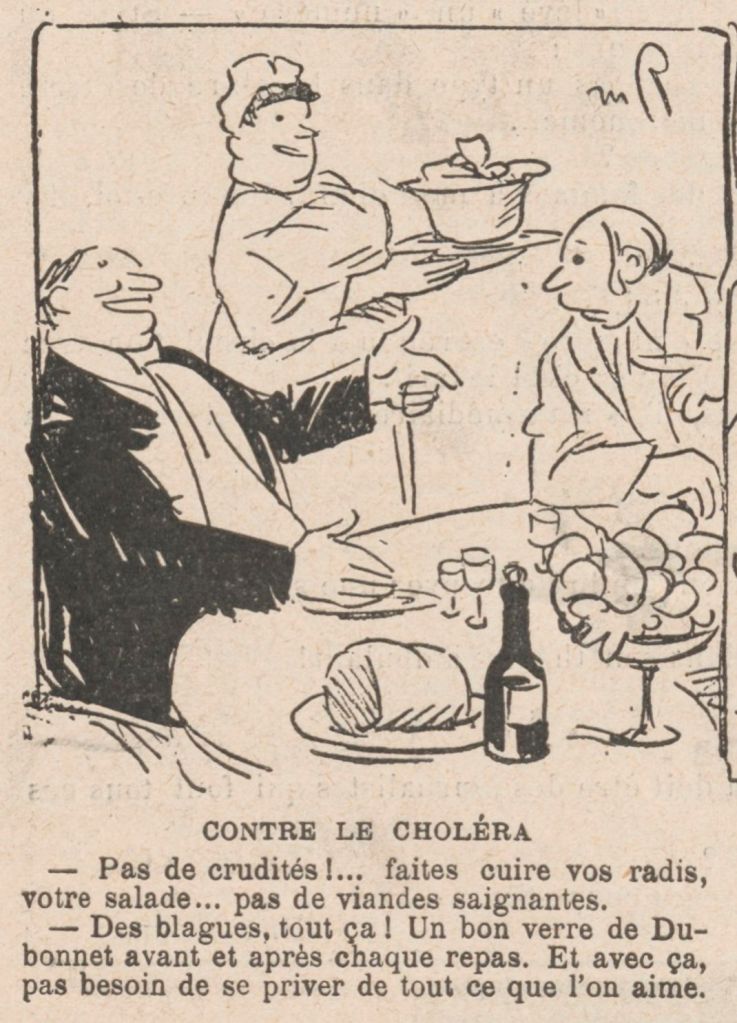

“No raw vegetables!… cook your radishes, your salad… no raw meats.”

“It’s all a joke! A good glass of [quinine-fortified] Dubonnet before and after every meal. And with that, no need to deprive yourself of everything you love.”

(Le Rire, Paris, 1911)

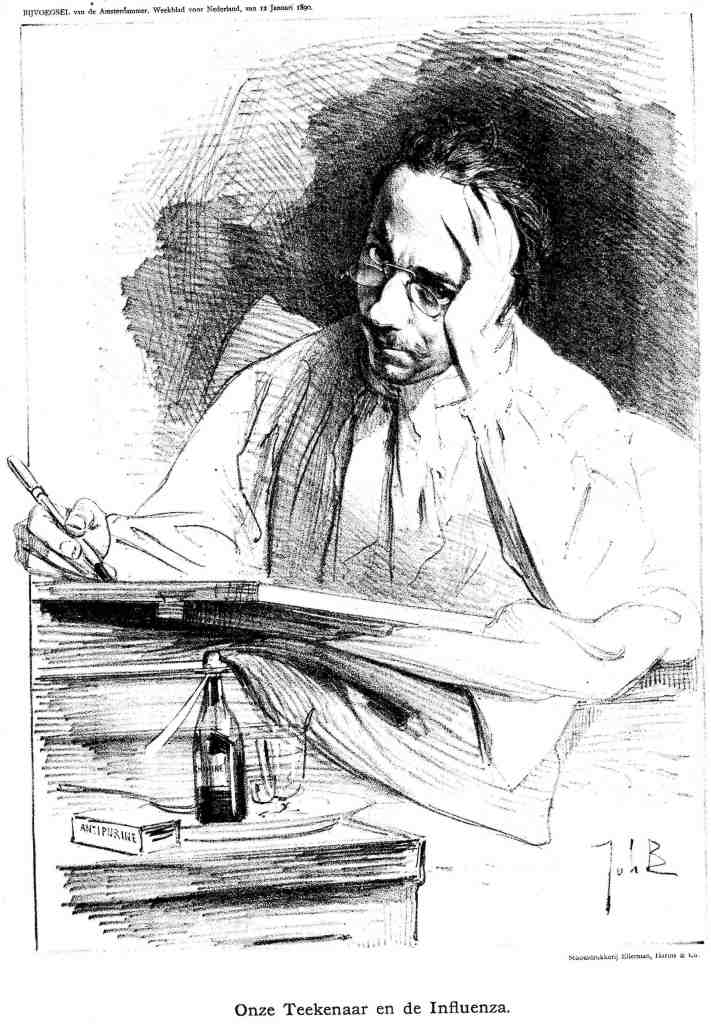

This spare image is fascinating, appearing when an influenza epidemic had prevailed for more than two months in the city of Amsterdam, at a dramatic cost of nearly one in thirty residents every week. The artist, his own medicaments at hand, seems to be contemplating, not so much his own clinical predicament, but how to represent the crisis in visual terms. The self-portrait might represent his interim solution to a dilemma he is not sure how to address satirically. (The irregular Bijvoegsel supplement was most often humorous in content.)

(De Amsterdammer, Amsterdam, 1890)

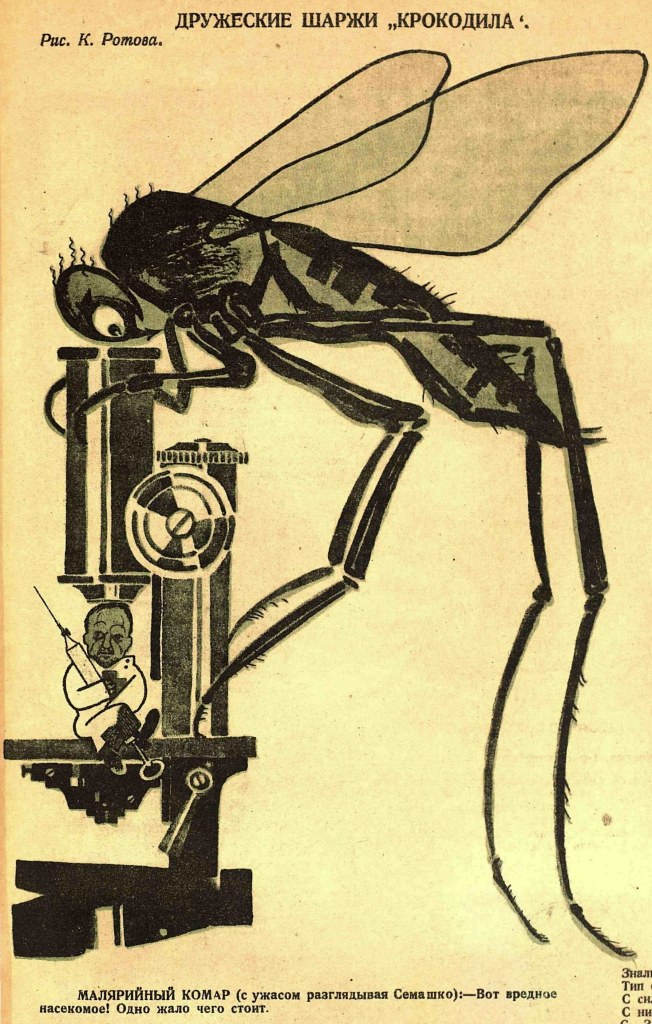

Malarial mosquito (gazing in horror at People’s Commissar of Health Nikolai Semashko): “Here is a harmful insect! One of its stings’ll cost you.”

(Krokodil, Moscow, 1925)

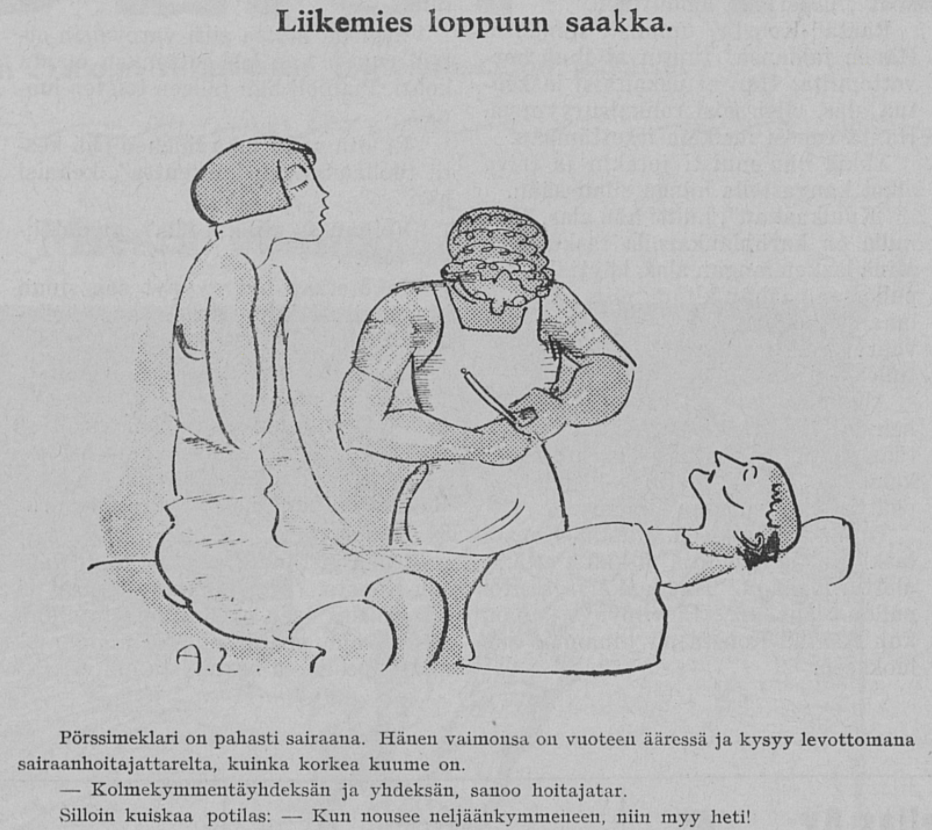

The stockbroker is seriously ill. His wife is at the bedside and anxiously asks the nurse how high the fever is.

“39.9 Celsius,” says the nurse.

Then the patient whispers: “When you get up to 40 C, sell immediately!”

(Tuulispää, Helsinki, 1929) (Not necessarily flu-related, but plausibly so.)

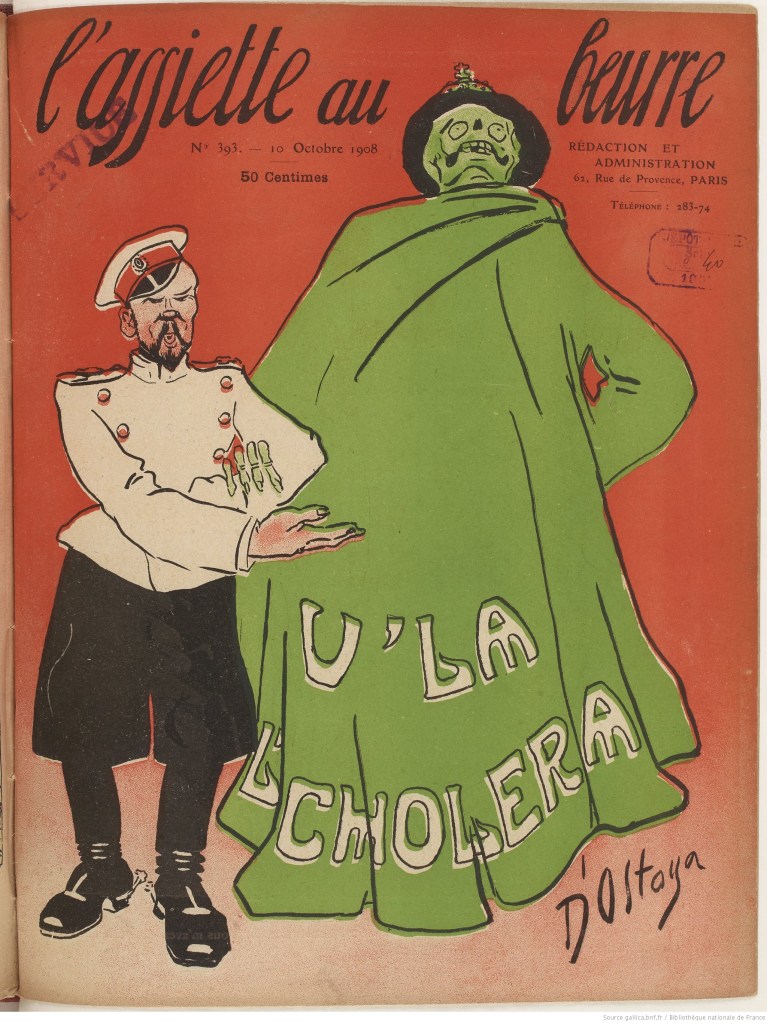

Since cholera spread from the Russian Empire further west in Europe in 1908, casting Tsar Nicholas II as the “host” was a popular gambit.

(L’Assiette au beurre, Paris, 1908)

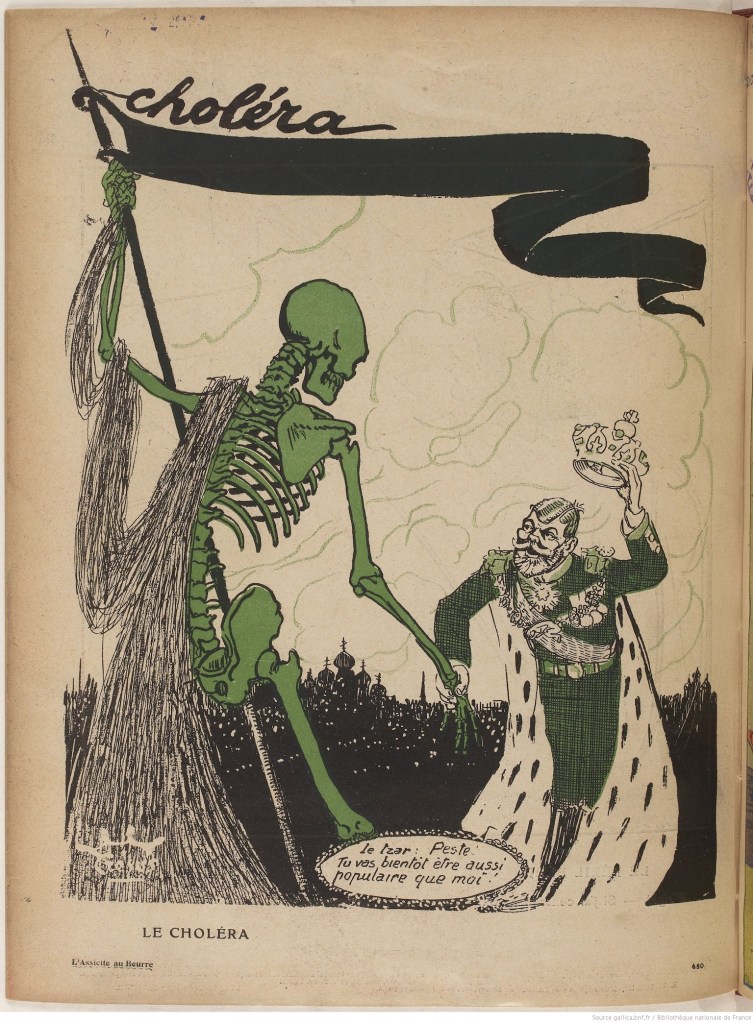

Similarly a week later:

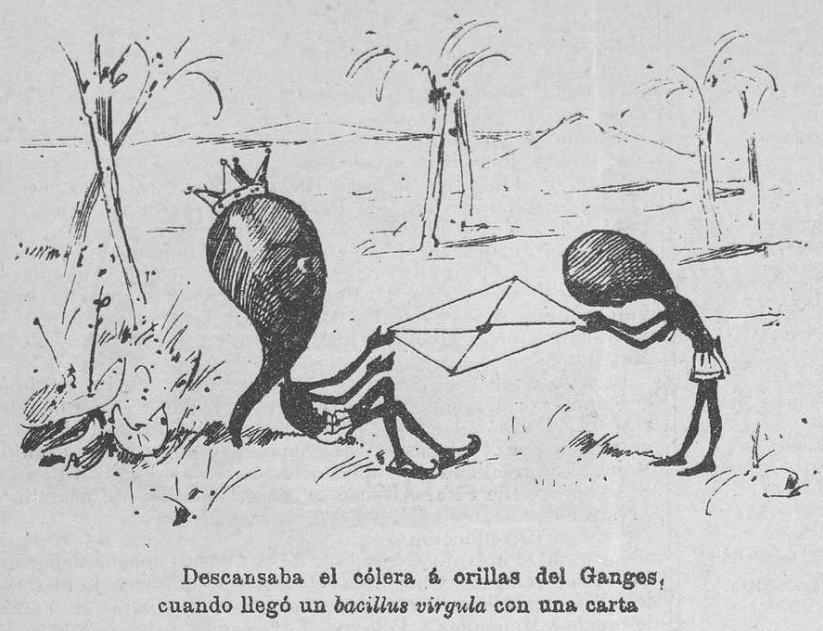

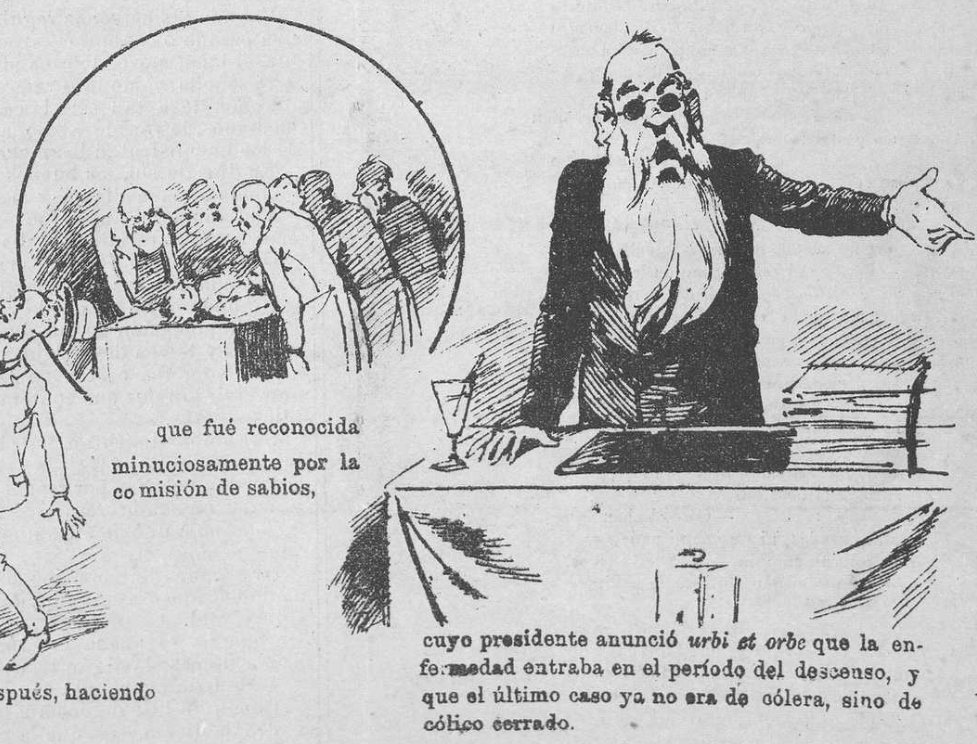

A multi-panel narrative from Madrid cómico (1890):

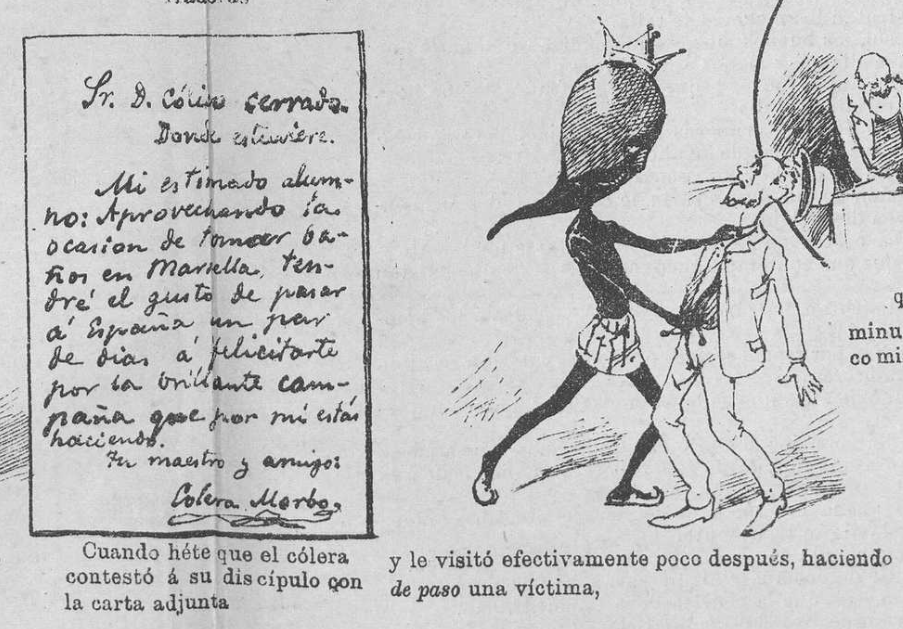

The cholera was resting on the banks of the Ganges when a virgula bacillus arrived with a letter that said the following:

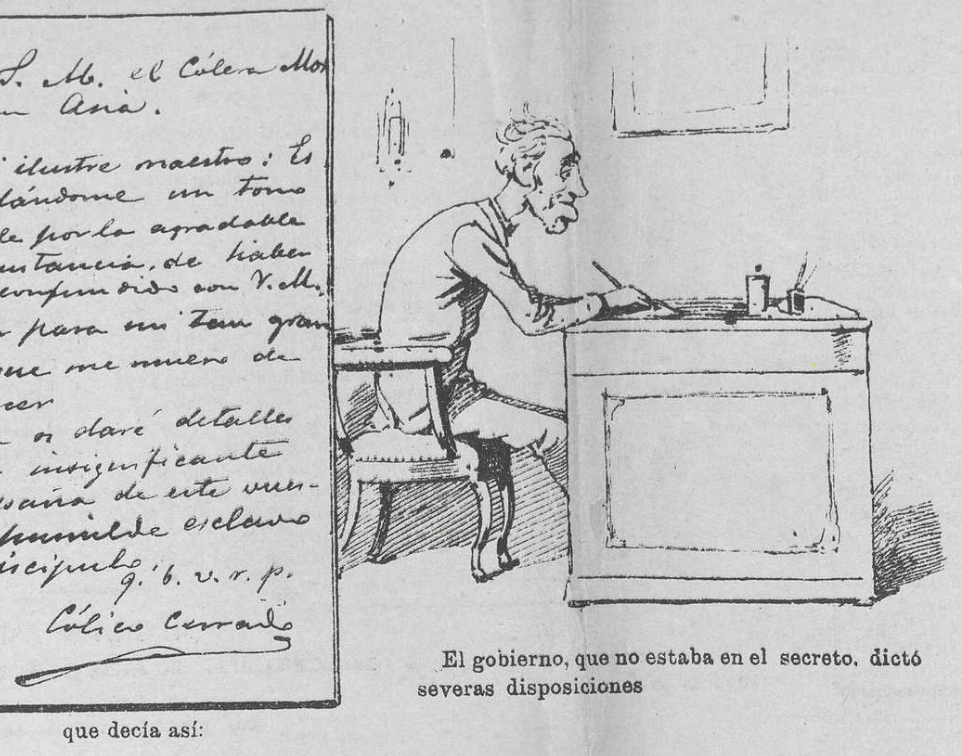

The governor, who was not secreted away, dictated severe provisions

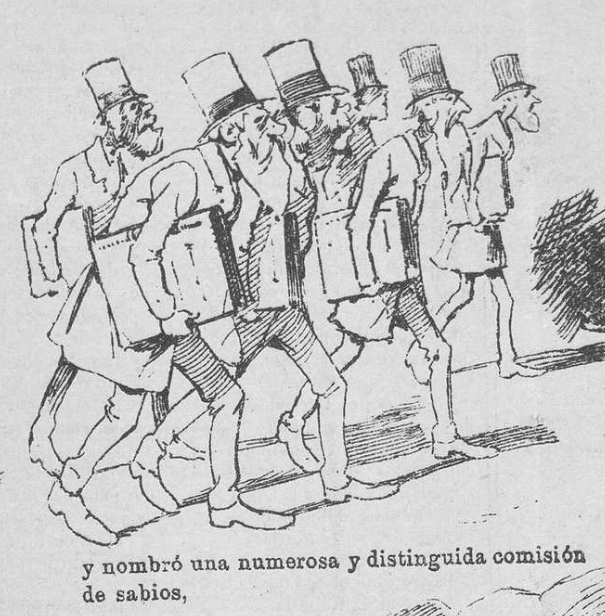

and appointed a numerous and distinguished commission of wise men,

which, before setting off, wrote an enlightening report on the necessary precautions in such cases.

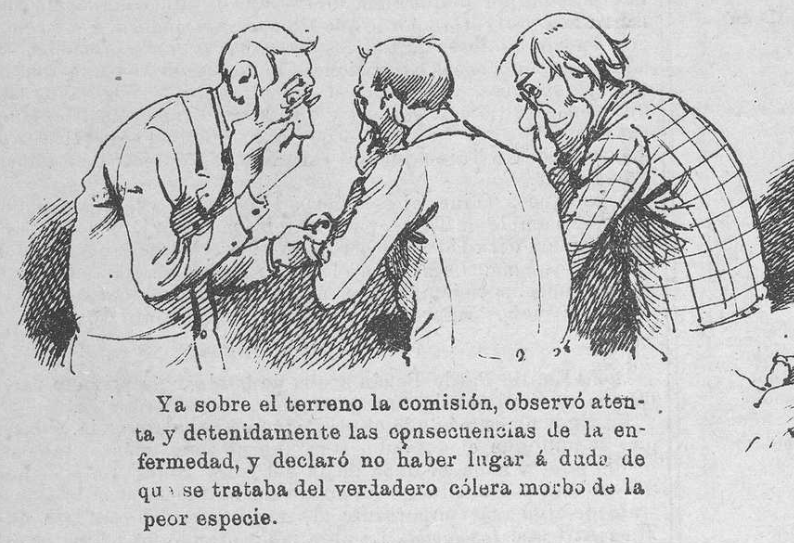

Already within the commission’s domain, the consequences of the disease were attentively and carefully observed, and it was declared that there is no doubt that it was the true morbid cholera of the worst kind.

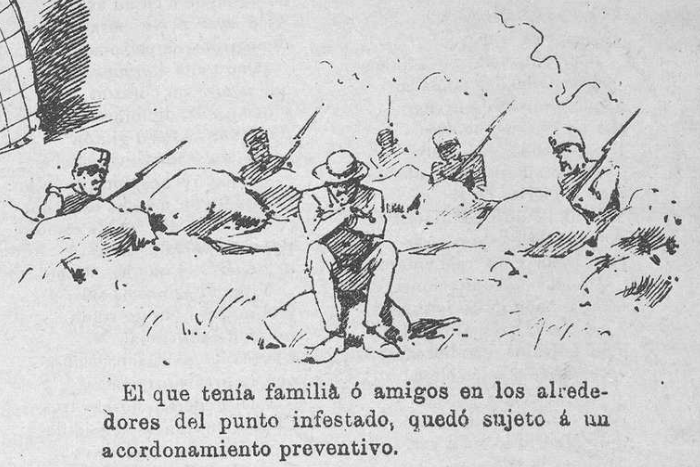

Anyone who had family or friends around the infected site was subject to a preventive cordon.

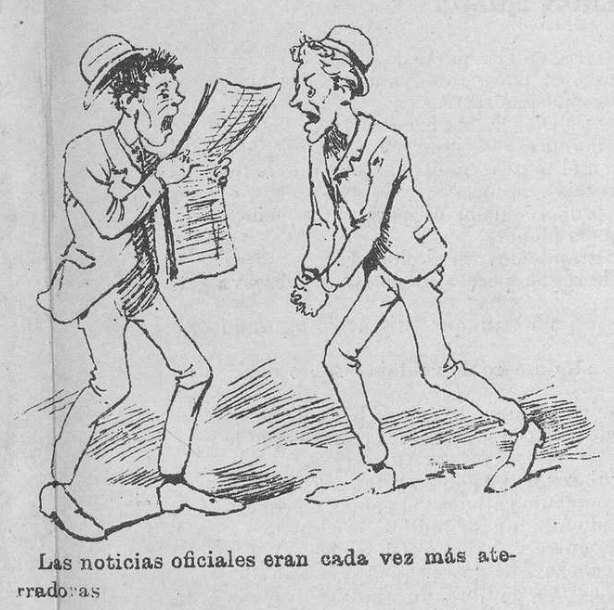

The official news was increasingly terrifying

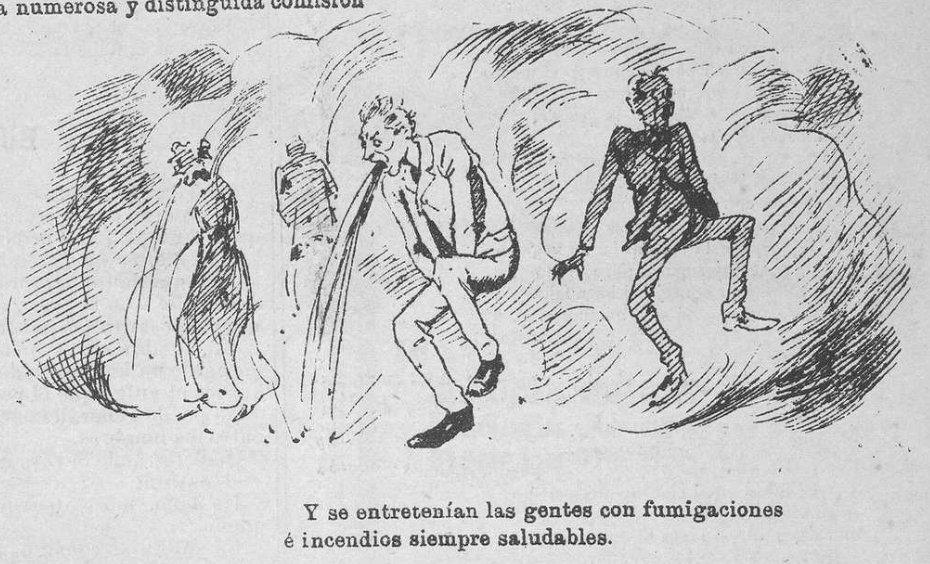

And people were entertained with always healthy fumigations and fires.

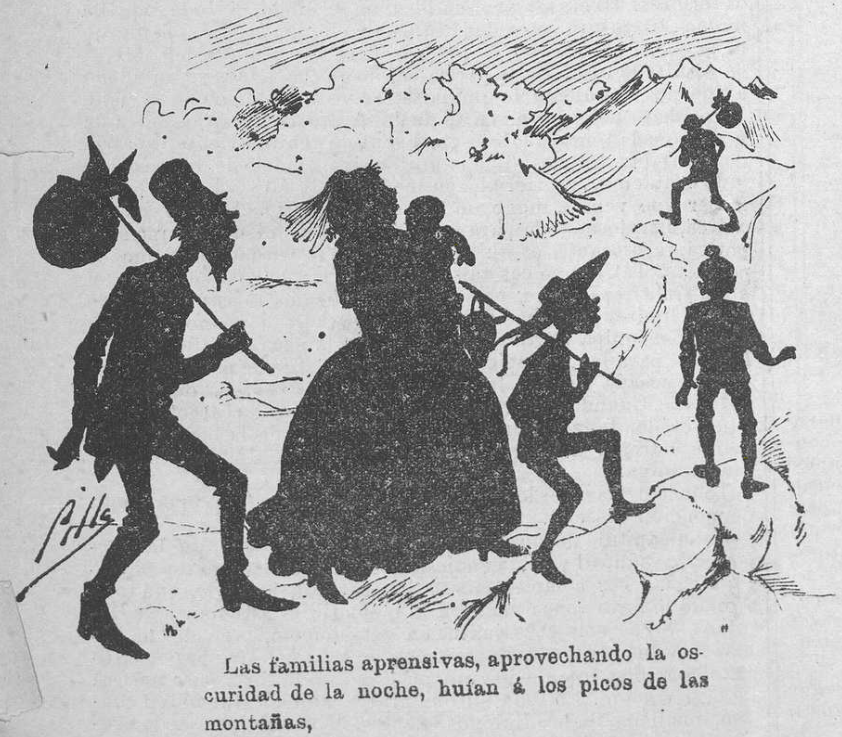

Apprehensive families, taking advantage of the darkness of the night, fled to the mountain peaks,

and clinics for travelers were established everywhere.

When the cholera answered his disciple with the attached letter and visited him shortly afterwards, making him a victim in passing,

it was meticulously recognized by the commission of wise men, whose president announced urbi et orbi that the disease was entering the period of decline, and that the last case was no longer cholera, but colic.

Professor: “Observe, gentlemen, the magnificent result of my new treatment of cholera.”

Students: “But he is dead!”

Professor: “He would be many times more dead if he had been treated with the old systems!…”

(Lo Spirito folletto, Milan, 1884)

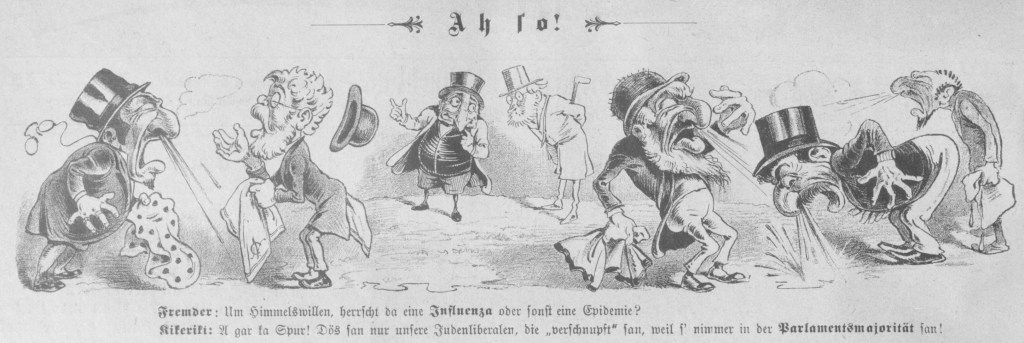

An uncomfortable reminder of the prevalent anti-Semitism in Vienna at the fin-de-siècle.

Stranger: “For heaven’s sake, does an influenza prevail there or some other kind of epidemic?”

Kikeriki: “Not a trace! This is only coming from our Jewish-Liberals, who are “sniffing” in irritation because they’re never in the parliamentary majority!”

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1897)

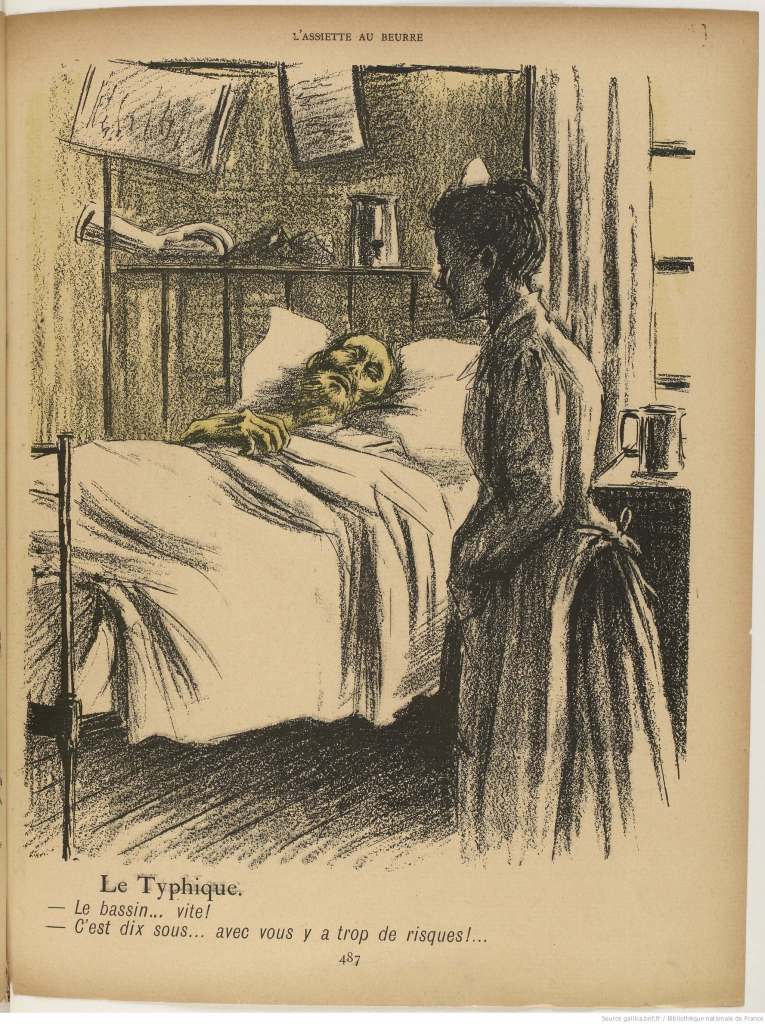

“The basin… quickly!”

“It costs ten sous… with you there are too many risks!…”

(L’Assiette au beurre, Paris, 1901)

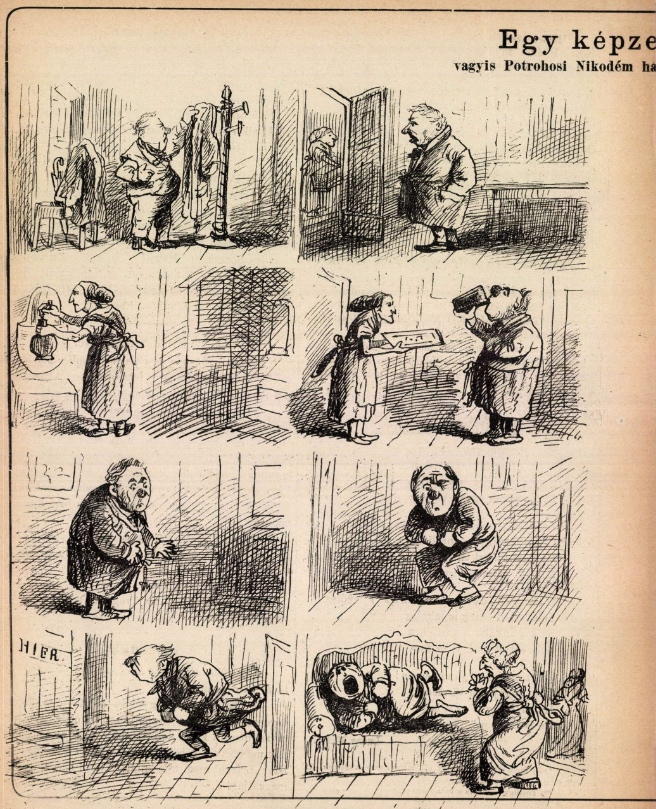

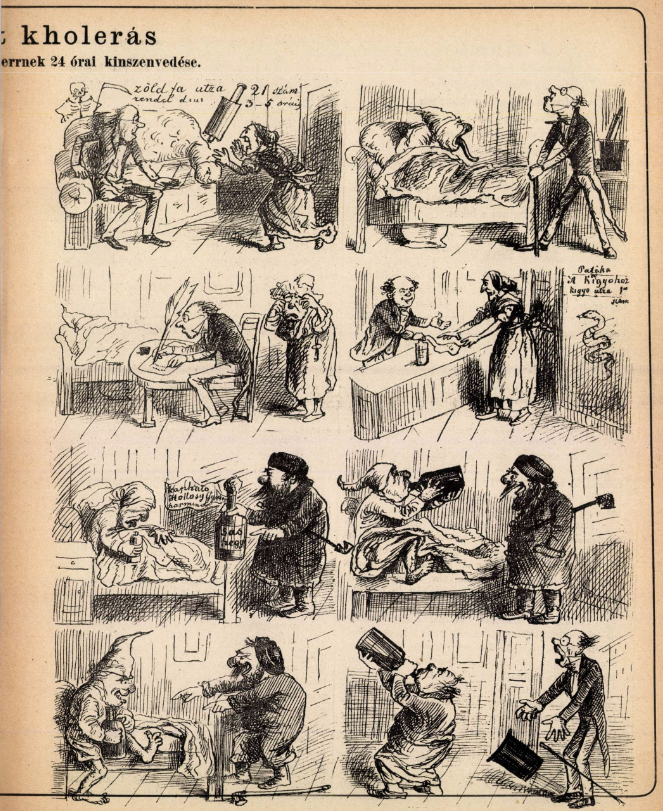

(Ludas Matyi, Budapest, 1872) (This would appear to be illustrating a triumph of alcoholic potions over clinical instructions.)