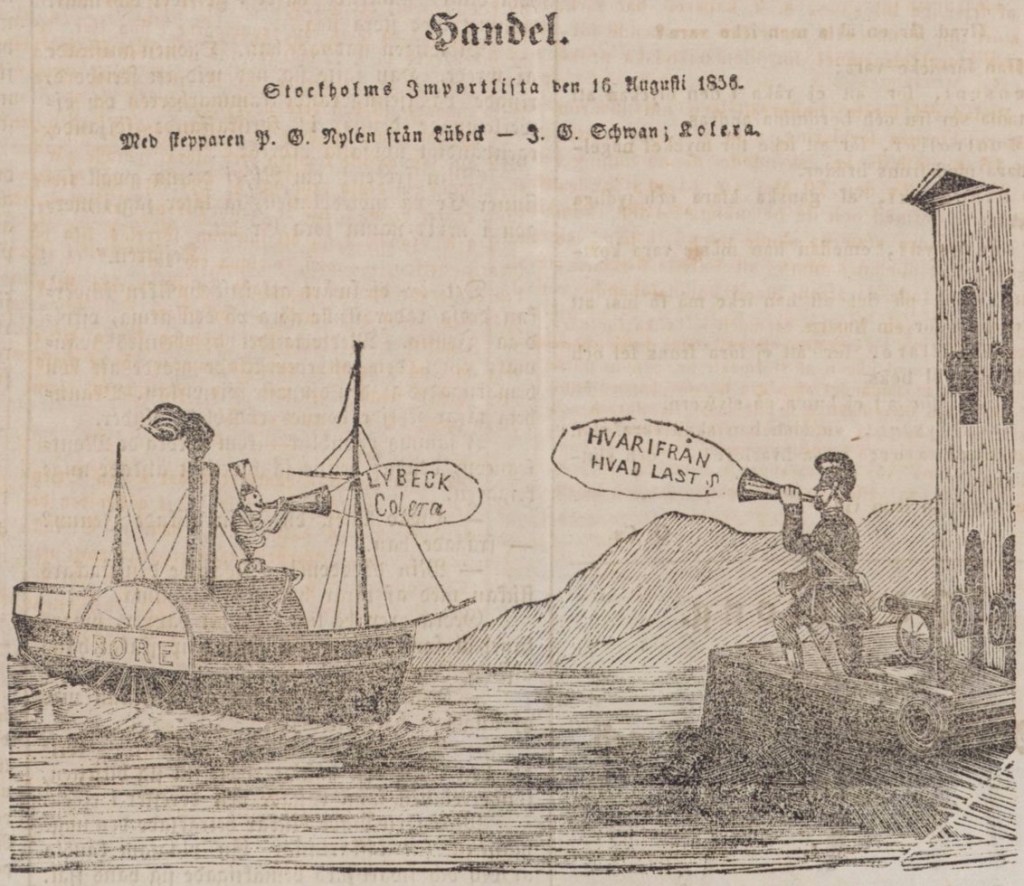

Stockholms import list, 16 August 1856.

With skipper P. G. Nylén from Lübeck — J. G. Schwan; cholera.

(The man on shore is calling out, “Where are you from? What is your cargo?”)

(Fäderneslandet, Stockholm, 1856)

Stockholms import list, 16 August 1856.

With skipper P. G. Nylén from Lübeck — J. G. Schwan; cholera.

(The man on shore is calling out, “Where are you from? What is your cargo?”)

(Fäderneslandet, Stockholm, 1856)

(Skåne is the southern country in Sweden on the eastern side of the Øresund Strait from Copenhagen. The specter of Cholera is reaching out from France.)

(accompanied by some playful verse which I cannot render in full, but here’s one pair of couplets)

But look into the distance! What do we get to see?

It is the cholera that is seen to prevail,

She, who explains all gaiety and caressing,

should she interfere with our play?!

(Fäderneslandet, Stockholm, 1884)

(I’ll only venture the first and last couplets that accompany this image.)

Mr. Sörensen! I have blocked the road for you.

You must not bring cholera to me.

…………

Yes, dear captain, turn on your engine

and sail so the sea trolls get the cholera!

(Fäderneslandet, Stockholm, 1892)

For early Swedish satirical press one should apparently look to Grönköpings Veckoblad, but so far as I can tell, there is no historical digital archive available. Rather by accident I’ve finally run across another potential Swedish contribution to this collection. Fäderneslandet (Fatherland) was a Stockholm newspaper in operation since 1830, achieving a rather large circulation by the 1870s. Sporting the subheading “Freedom Work Justice,” it apparently fostered a politically radical stance, but more often functioned as a scandalous broadsheet. In any event, they occasionally published cartoons, including this one from during the cholera pandemic of 1892, accompanied by rhymed couplets in the original.

(Fäderneslandet, Stockholm, 1892)

Attention! This newspaper is reporting:

“The Traveling Kaiser is not coming.”

Because of cholera? Yes, it’s a given,

he cannot defy it – no.

But, alas, organizers of festivities,

Officers and gentlemen who bear the sword!

Yes, major patrons and merchants,

it’s a blow to the bill of goods.

That Kaiser Wilhelm would visit us,

it was just said in all the squares.

And we wanted to hold a feast for him

in our proud Gothenburg.

We intended to light things up

and put on the fireworks.

“He will decorate us for this

with ribbons and medals,” we thought.

But these were golden illusions

they evaporated away for this time.

Yes, now by forests [of newspapers?] and millions [of kroner?]

our nose has become terribly long.

Whose fault it is, we all know,

it is cholera, at the knees of the gods!

Oh, may it go to Gehenna

and be put there in quarantine!

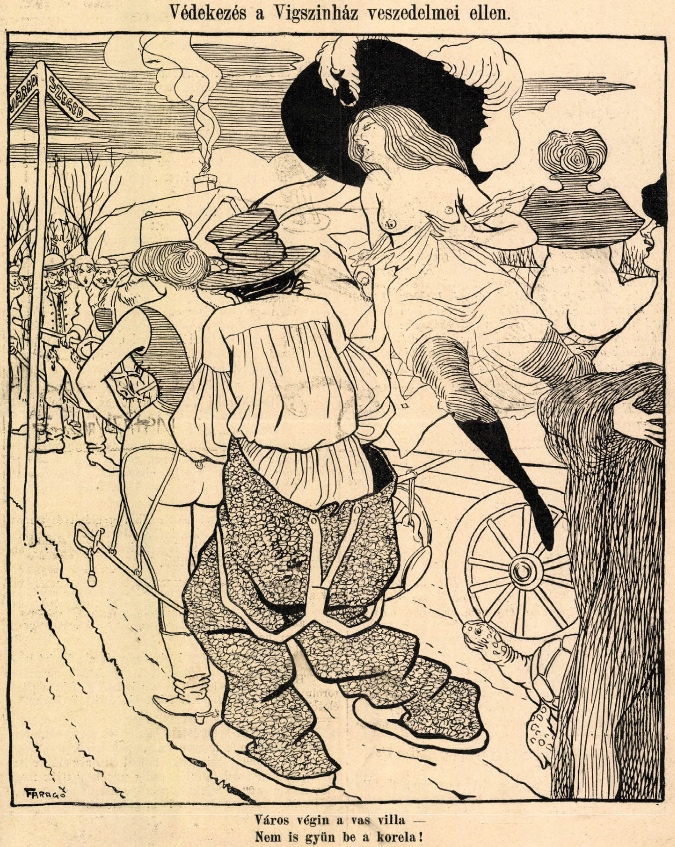

(The Vigszinház or Comedy Theater was generally the most popular in Budapest.)

The pitchfork at the city outskirts —

Even chorela doesn’t come in!

(The orthography signals something other than high diction. Note the phonetic metathesis of “cholera.” Contemporaries would have understood the reference to a folksong lamenting that cholera didn’t affect lords or priests, only the poor peasants.)

(Borsszem Jankó, Budapest, 1900)

“Pardner, did you hear that there is chorela [cholera] among the people of Újpest? Even real chorela!”

“Surely it would be better if their money was real and their chorela fake.”

(Újpest, or New Pest, was a recently-incorporated town on the north side of Budapest proper, and a higher proportion of its residents were Jewish, though not from the bourgeois elite.)

(Kakas Márton, Budapest, 1911)

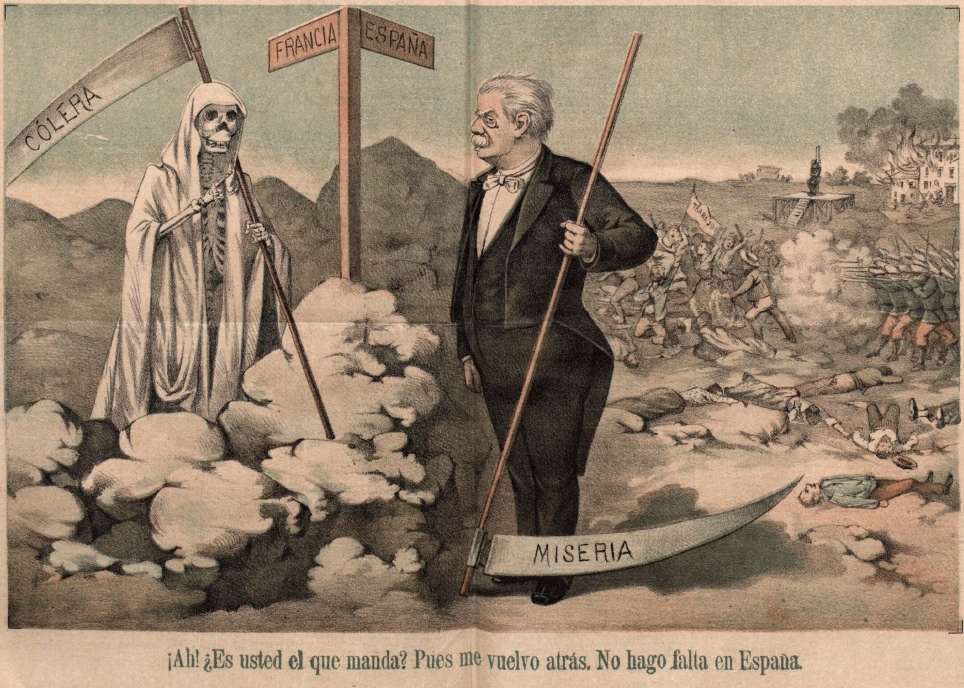

Cholera at the French-Spanish border, to Spanish prime minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo: “Ah! Are you the boss? Well, I’ll head back. I’m not needed in Spain.”

In January Andalusian anarchist workers associations had tried to take control of Jerez de la Frontera, an action that was violently suppressed by the government. The following month four anarchist workers were executed, but not before a small bomb was set off in the Plaza Real in Barcelona. Just weeks before this image was published, greengrocers in Madrid launched a “mutiny,” a popular revolt in the face of new municipal taxes. The Conservative Cánovas, then serving his fifth turn as prime minister, strongly resisted expanding suffrage to the working class. (See a previous issue for another excellent image; El Motin was unsurprisingly deeply hostile to monarchist politicians.) He also pursued a hard line against Cuban independence. He was eventually assassinated by an Italian anarchist in 1897.

(El Motin, Madrid, 1892)

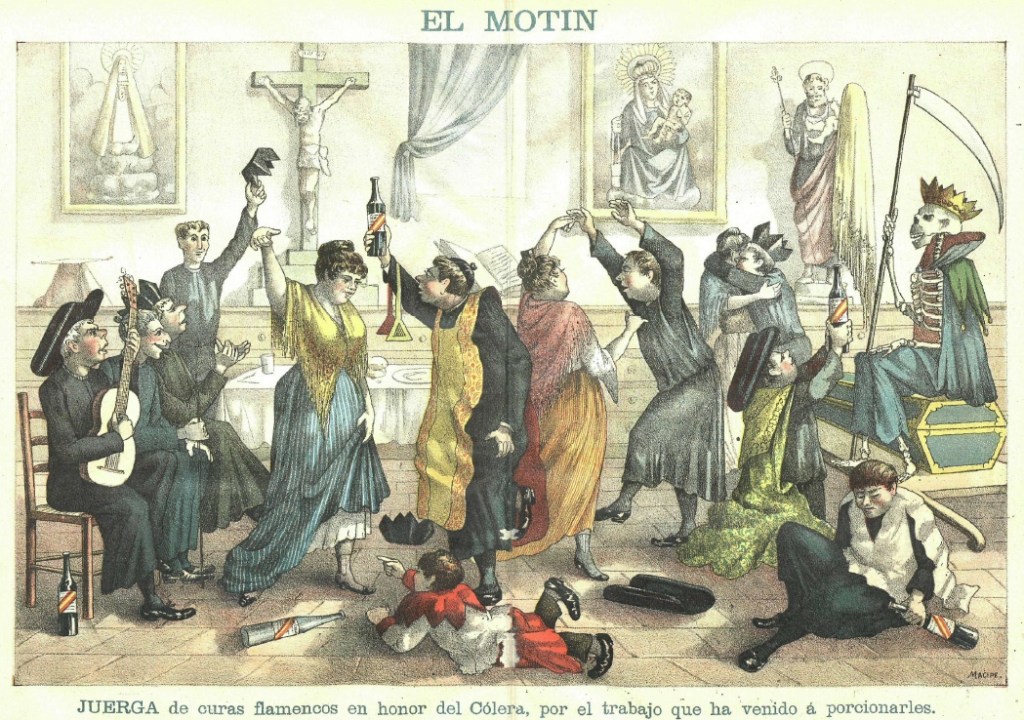

Flamenco priests binge in honor of Cholera, for the work that has come to their provisioning [?].

(El Motin, Madrid, 1885)

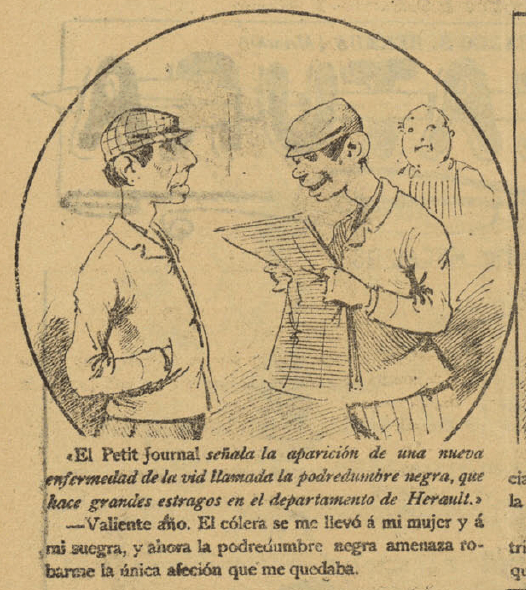

“The Petit Journal reports the appearance of a new vine disease called black rot, which is ravaging the department of Herault.”

“Brave year. The cholera took my wife and my mother-in-law, and now the black rot threatens to rob me of the only affection that remained.”

(La Caricatura, Madrid, 1885)

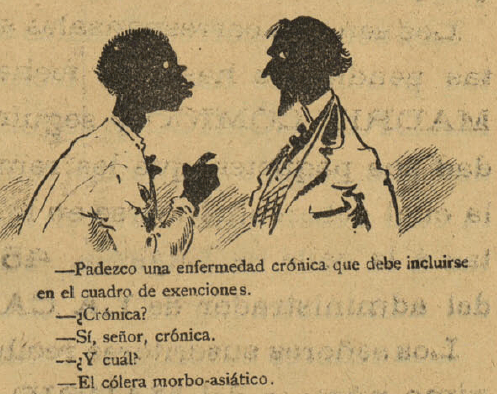

“I have a chronic illness that should be included in the exemption chart.”

“Chronic?”

“Yes, sir, chronic.”

“And what?”

“Cholera morbo-asiatico.”

(Another Mecachis cartoon from La Caricatura, Madrid, 1885)

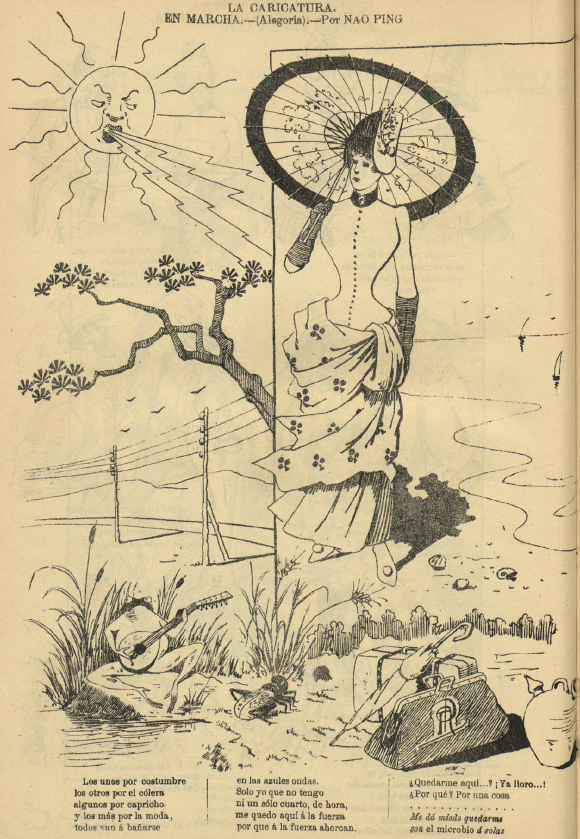

Some out of habit

others because of the cholera

some on a whim

and most for fashion,

everyone is going to bathe

in the blue waves.

Only I who do not have

not a single quarter of an hour,

I stay here by force

because they hang by force.

Stay here…? I’m already crying…!

Why? For one thing

…………………….

I’m afraid to be

alone with the microbe

(La Caricatura, Madrid, 1885) (Sadly I cannot say anything about Nao Ping. This one is rich with possibility.)

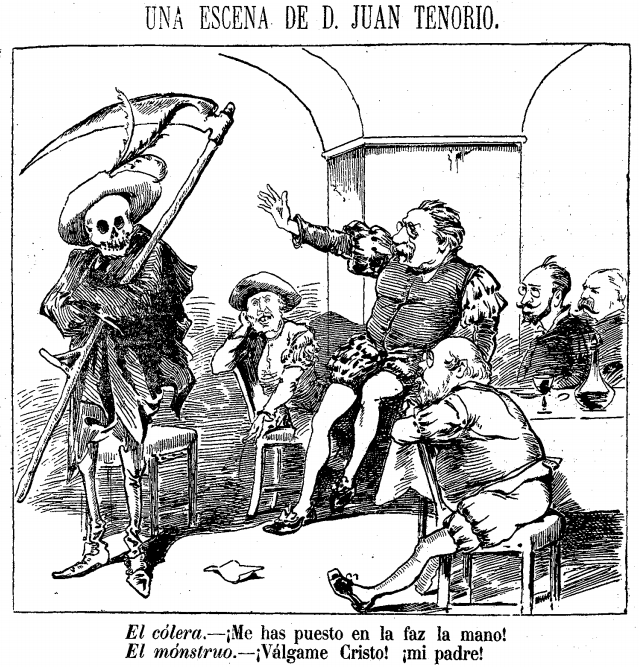

Don Juan Tenorio (the Seducer) was a 1844 play by José Zorrilla that retold the Don Juan legend for modern Spanish audiences. The object of satire here is prime minister Antonio Cánovas del Costillo, sometimes referred to as “the monster” for his curious combination of intellectual hauteur and political brutality.

Cholera: “You have slapped me in the face!” [i.e., “I demand satisfaction!”]

The monster: “Christ almighty! My father!”

(El Busilis, Barcelona, 1884)

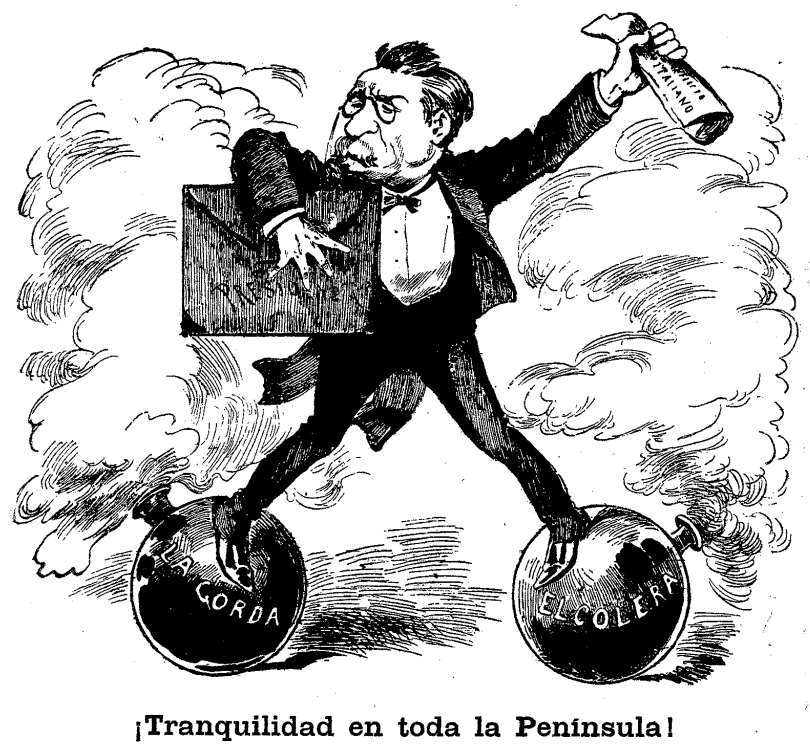

Without the lifesaver of morbid cholera, the ministry would have already drowned, because it was up to its neck in water.

(El Busilis, Madrid, 1884)

(El Busilis, Barcelona, 1884)

(This is not a freestanding cartoon, but one of several small illustrations that accompany an essay by this title. A rather rough translation of a bit of the surrounding text follows. I’m including this item because it is the earliest available Spanish example I have located so far.)

The recent carnival in Madrid has been bountiful in amorous intrigues, very weighty puns, and acts of honor.

As if revolutions, wars, typhus, influenza, morbid cholera, national pneumonia, and doctors who take death as their lackey were not enough, there are men who have such little esteem for their lives, that I must get away from all that chaff pretending to be skewered like veal on a spit. This would be dreadful if, fortunately, there were not charitable souls in the world who would try to convert the fiery impetus of the Matachines [carnivalesque dance troupes] into healthy prudence… [A metaphor or Aesopian tag for revolutionary factions, which did not win the day in 1848? I am out of my depth here.]

(La Linterna mágica, Madrid, 1849)