Young Europe: “Hopefully there are nicer toys in the new boxes than in the old ones [war, influenza, Bolsheviks].”

(Nebelspalter, Zurich, 1919)

Young Europe: “Hopefully there are nicer toys in the new boxes than in the old ones [war, influenza, Bolsheviks].”

(Nebelspalter, Zurich, 1919)

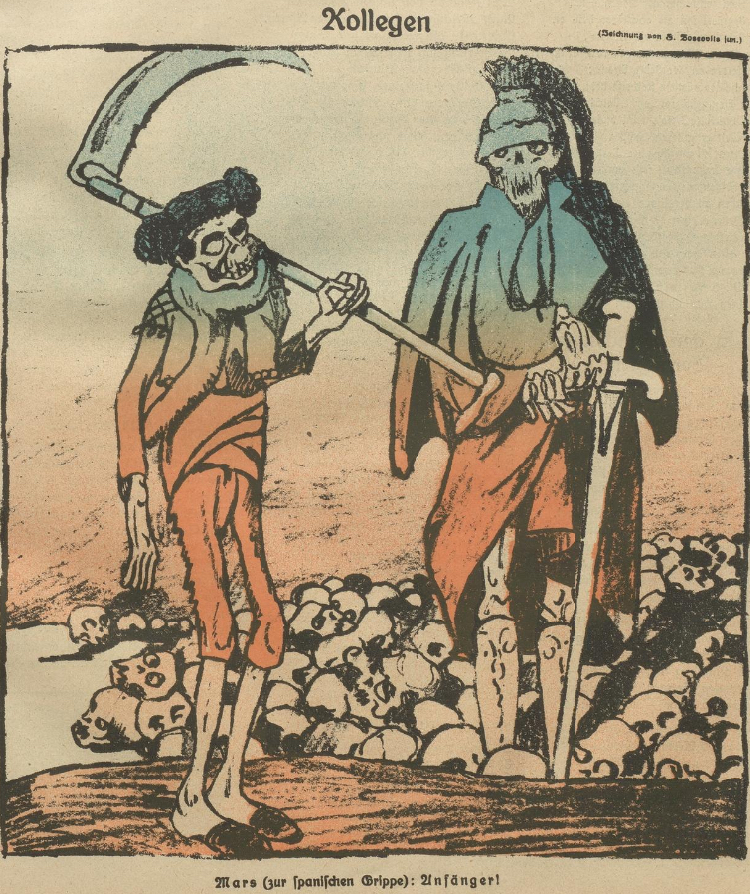

Mars (to the Spanish flu): “Beginner!”

(Nebelspalter, Zurich, 1918)

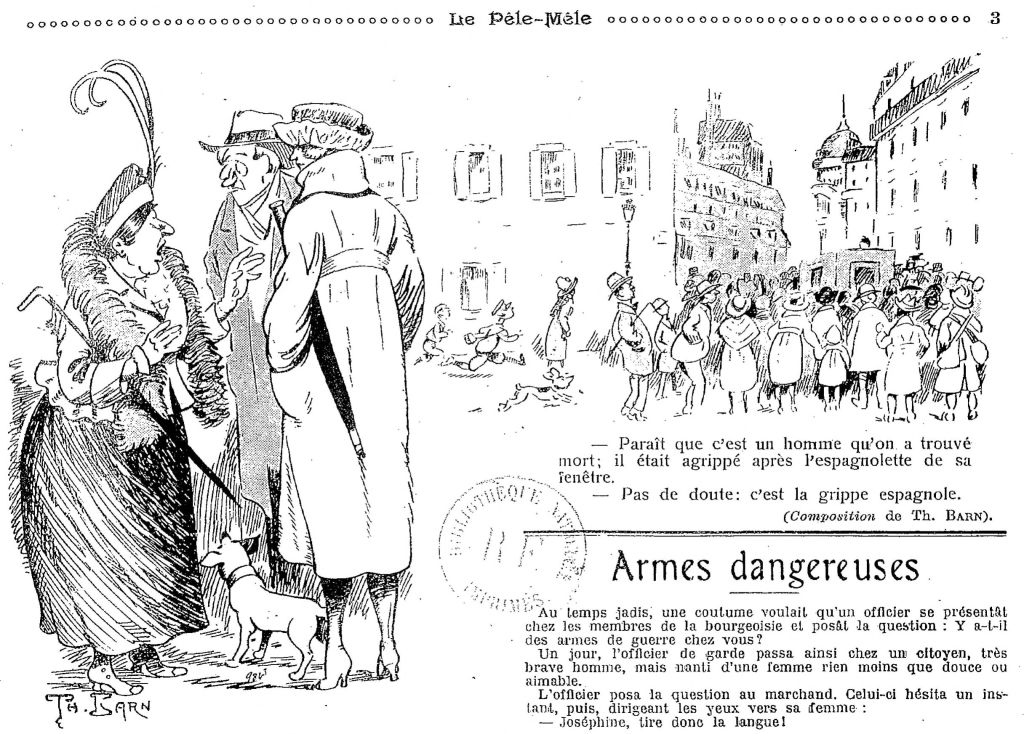

There was no immunity from tortuous puns during the great influenza pandemic.

“It seems a man was found dead; he was clutching at the espagnolette (window fastening) of his window.”

“No doubt about it: it was the Spanish flu.”

(Le Pêle-mêle, Paris, 1919)

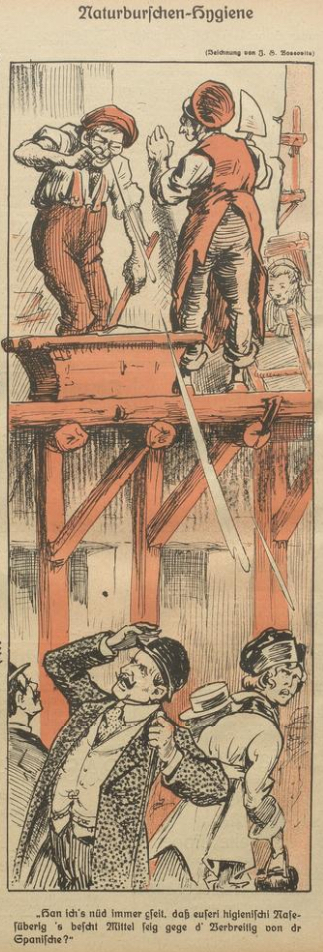

As always in matters of hygiene, delicate questions of class are lurking in the foreground. I can’t pretend to translate Schweizerdeutsch properly, but the basic sentiment of the fellow clearing his nose seems to be that he’s always said that their hygienic nose-clearing is the best means against the spread of Spanish flu. Clearly the good bourgeois passers-by feel differently.

(Nebelspalter, Zurich, 1918)

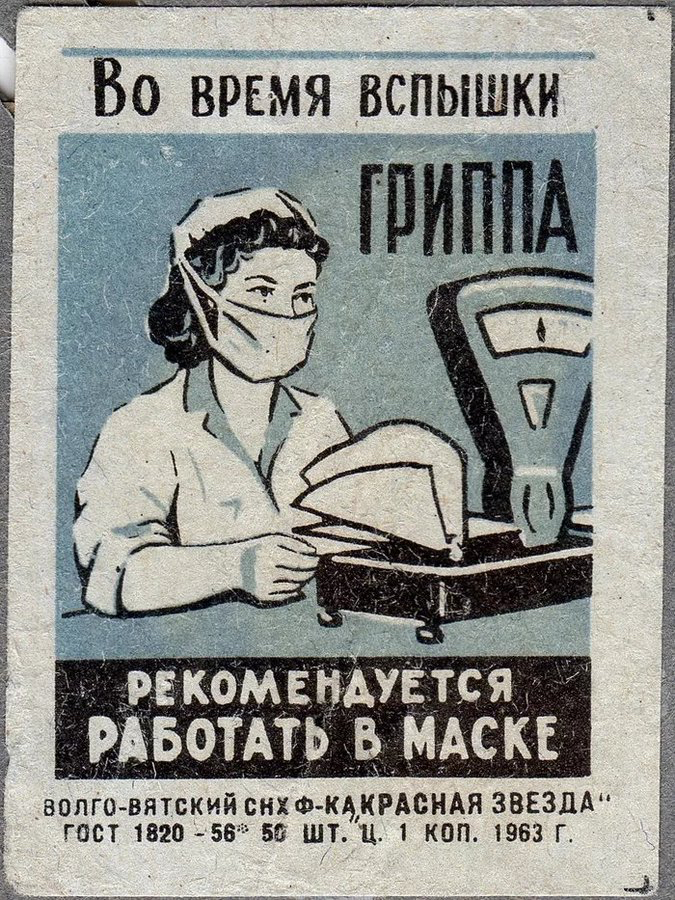

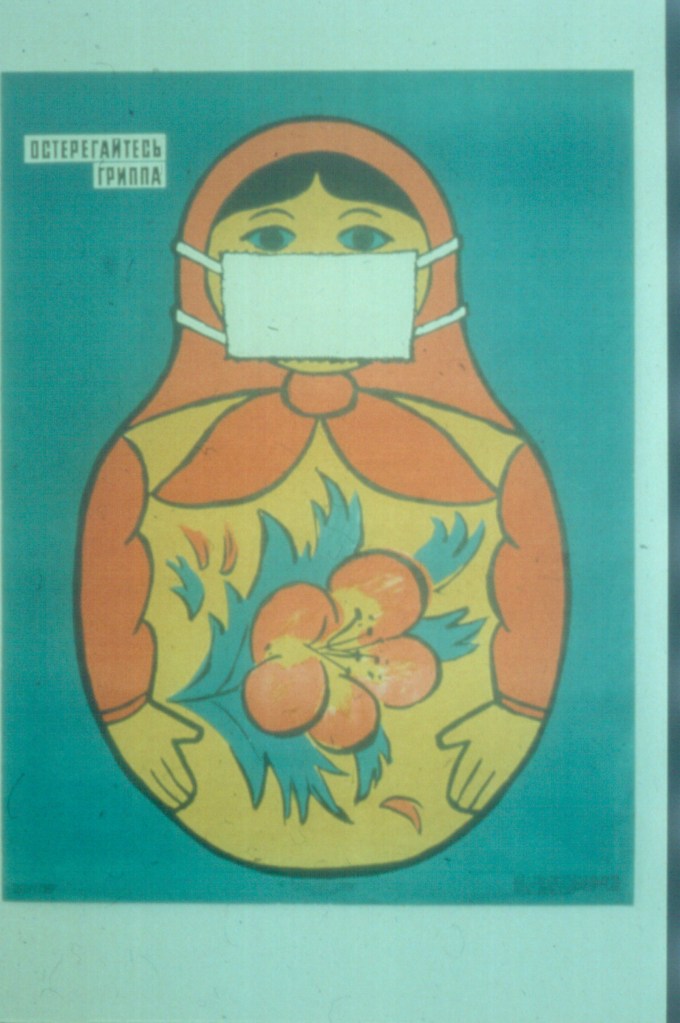

During flu outbreaks working in masks is recommended. (Soviet Union, 1963)

(State Museum of St. Petersburg History, with thanks to Svetlana Lazutina)

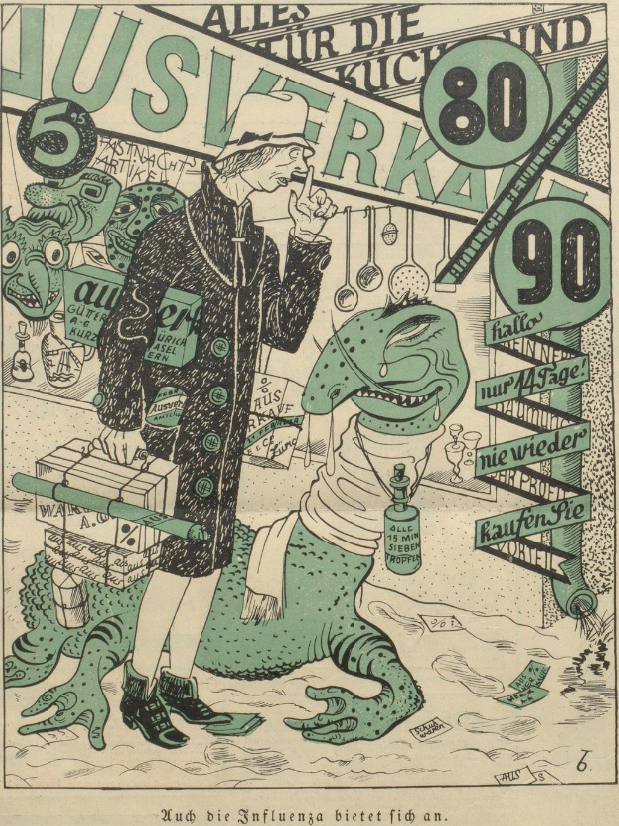

“Influenza is also on offer.” Shopping with the Swiss satirical magazine Nebelspalter, 1929.

Russian matryoshka doll with face mask, 1974.

(deutsche fotothek)

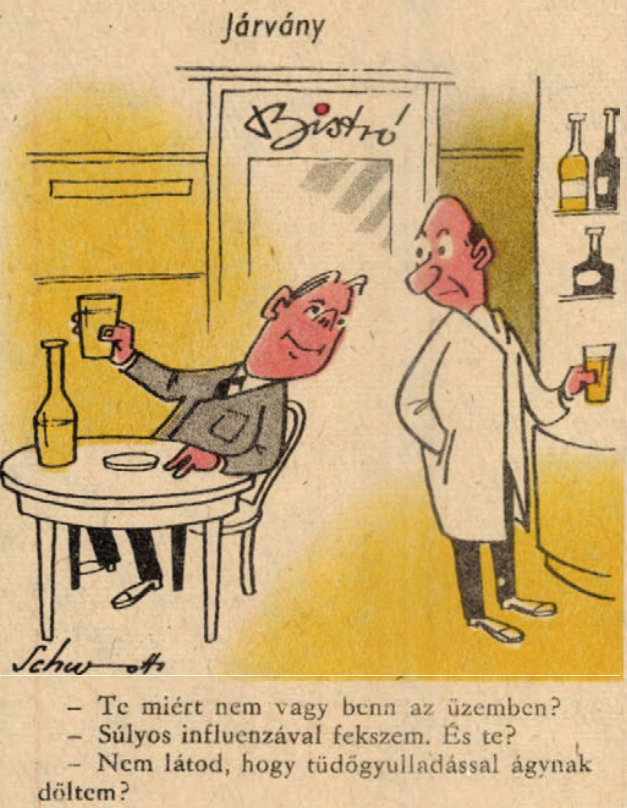

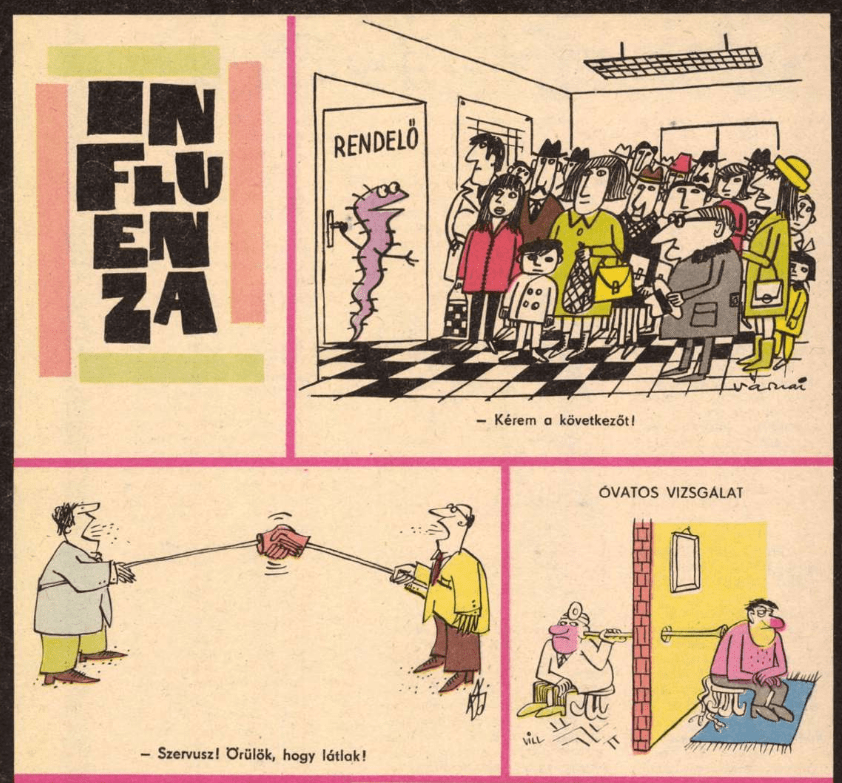

“Why aren’t you in the plant?”

“I’m down with severe flu. And you?”

“Can’t you see I was bedridden with pneumonia?”

(Ludas Matyi, 1966)

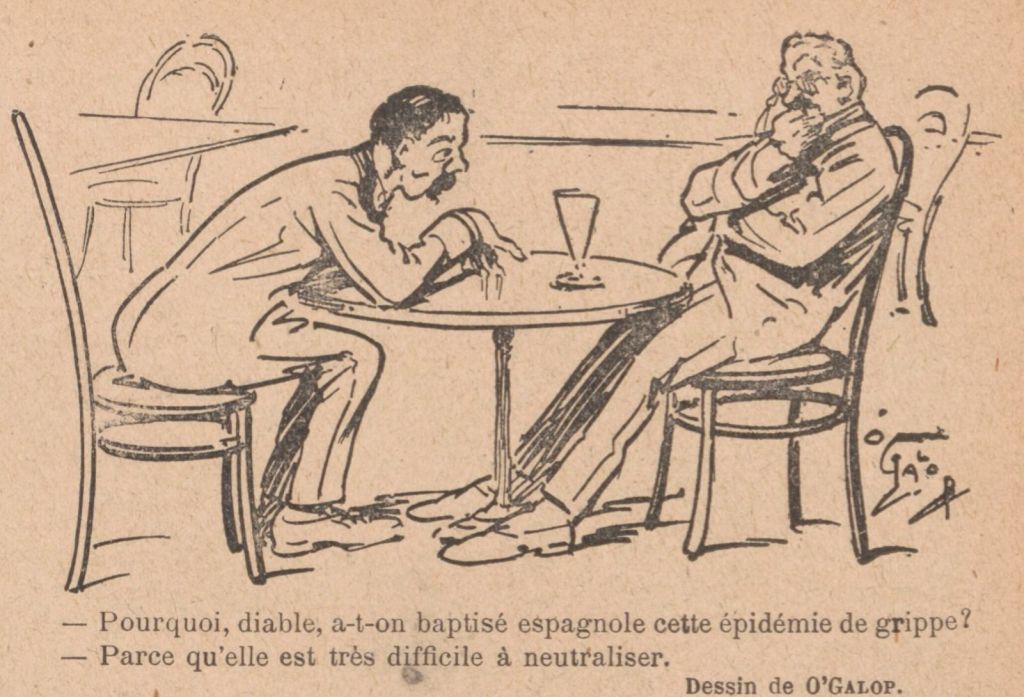

“Why the hell has this flu epidemic been dubbed Spanish?”

“Because it is very difficult to neutralize.”

(Le Rire, Paris, 1918)

“Say Bunny, did you have the Spanish thing?”

“Not that. But I did have a Bulgarian.”

(Borsszem Jankó, Budapest, 1920)

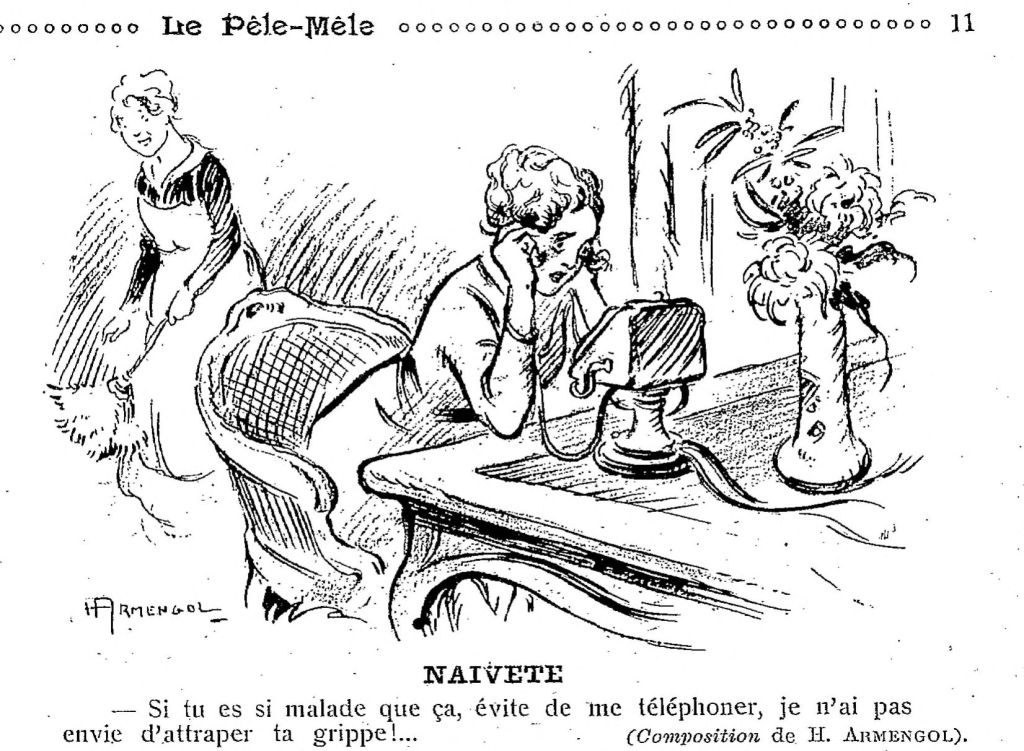

“If you’re that sick, don’t call me, I don’t want to catch your flu! …”

(Le Pêle-mêle, France, 1919) (For the 5G conspiracy theorists.)

This advertisement from 1927 for Formamint lozenges nicely captures some present dilemmas. The Berlin bacteriologist Max Piorkowski developed these anti-bacterial pills before World War I, when they were already widely marketed. During the 1918 influenza pandemic, when very little was known about the properties of viruses, the overwhelming cause of death was secondary infection stemming from bacterial pneumonia. Formamint was then sold for its antiseptic properties as an aid to avoiding contagion risks. The active ingredient was formaldehyde (now thought to be a carcinogen at higher exposures), bound with sugar and citric acid for convenient oral administration. Notice how the advertisement conflates the site of risk—a crowded movie theater—with the site of the didactic commercial insight. “The risk of contagion grows if many people gather, such as in theaters, cinemas, concert halls, on trains and trams, in schools, public assemblies and associations.” The screen depicts three different slide cross-sections of “influenza bacteria” (sic). The first slide, full of bacteria, did not have the benefit of Formamint. The second slide shows the reduction in bacteria by ingesting three lozenges, while the third slide, free of bacteria, comes courtesy of five lozenges. The obvious implication: take a lozenge to assuage your public health anxiety. If someone asks, “What have you got to lose?“, exercise caution before taking magic pills. (Austrian National Library)

(Compare also this earlier advertisement in English. It would seem that it had a strong market among war veterans.) On the more complex reasons for imputing the disease to Bacillus influenzae during the war, see Michael Bresalier, “Fighting flu: Military pathology, vaccines, and the conflicted identity of the 1918-19 pandemic in Britain,” J. Hist. Med. 68 (2013).

Flu sufferers in masks.

(Kronen Zeitung, Vienna, 1919)

Mr. Kankkus: “Pekka told me that cognac is also the best medicine for Spanish disease. I am happy to believe that, because now I have no fear of Spanish disease.

By the way, I think the whole thing about Spanish disease is just nonsense.”

Mrs. Kankkus: “I wonder if my husband could die of Spanish disease?”

Doctor: “No … but delirium tremens.” (Tuulispää, Finland, 1920)