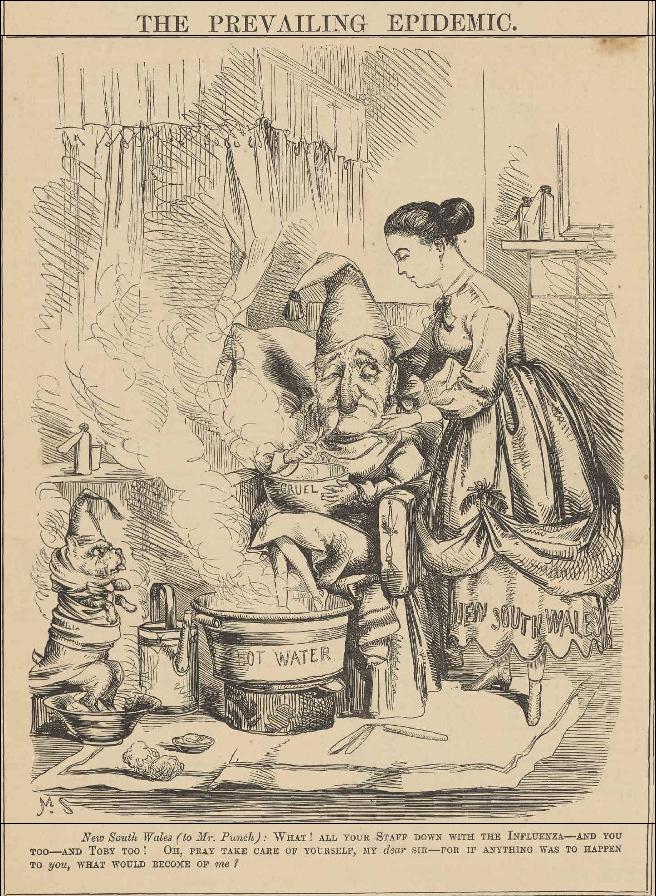

Sydney Punch, 1868

Sydney Punch, 1868

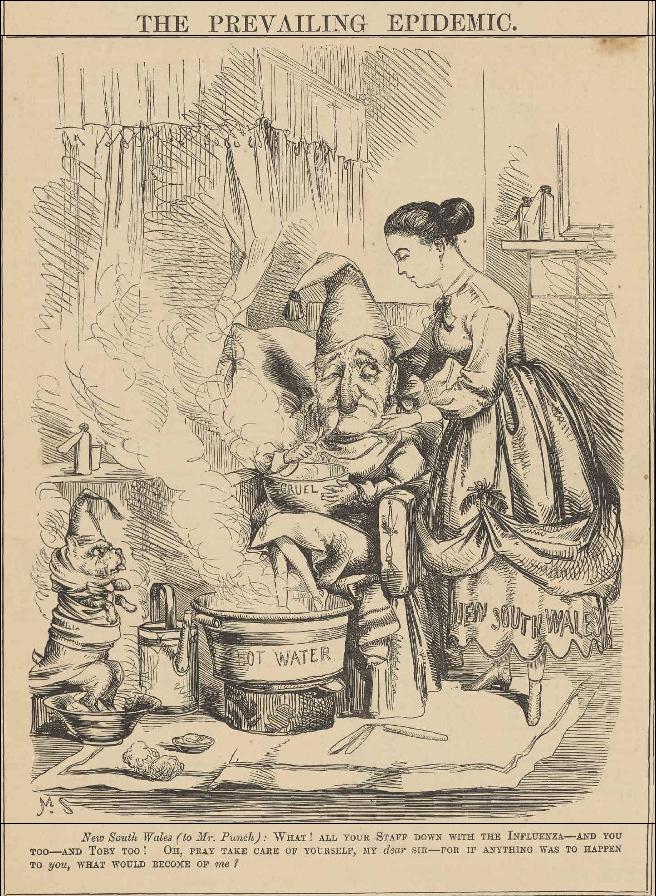

Ringmaster Fitz: “Now then, Dummy, jump through the hoops.”

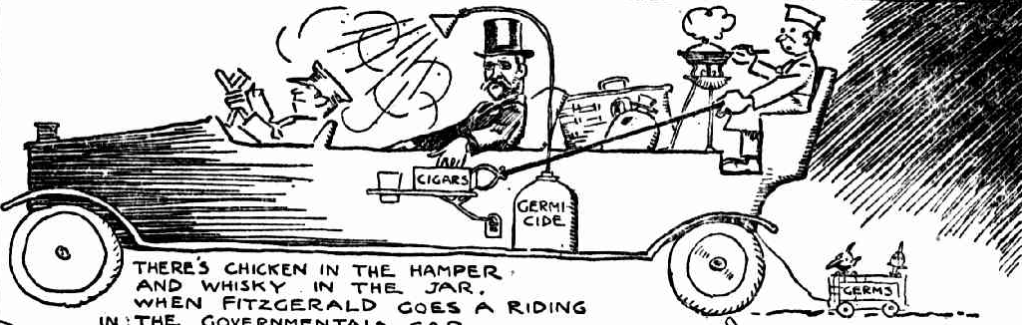

(Smith’s Weekly, Sydney, 1919)

John Daniel Fitzgerald, minister of public health in New South Wales during the global flu pandemic, is mocked here for his aggressive response to the crisis. Elsewhere Smith’s Weekly referred to him as “lord of the masks and master of the microbes.” See also this image depicting him making his disinfected rounds in a government vehicle:

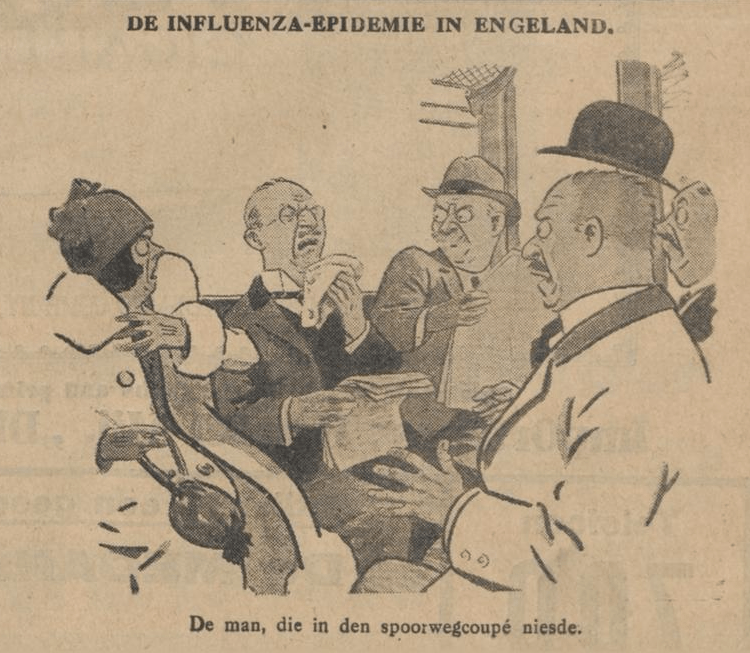

The man who sneezed in the railway compartment.

(De Sumatra post, 1925) (Compare these Hungarian and Czech variants.)

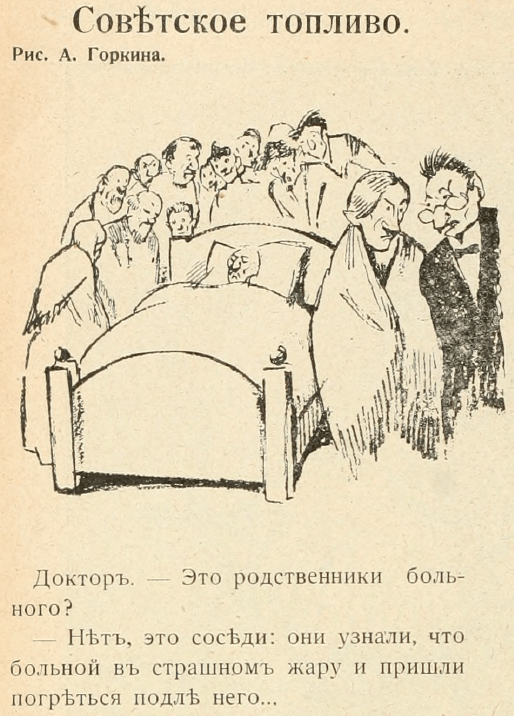

Doctor: “Are those relatives of the patient?”

“No, those are neighbors: they found out that the patient has a terrible fever and came to warm up around him.”

(Bich, Paris, 1920) (Compare a similar German cartoon from 1847 in Fliegende Blätter)

Der neue Tag in Vienna printed a cartoon with a similar theme in 1919, apparently reprinted from a French source:

Title: “You have to know how to help yourself”

“Just stick close to Grandpa. He has the fever. Perhaps you’ll get warm near him.”

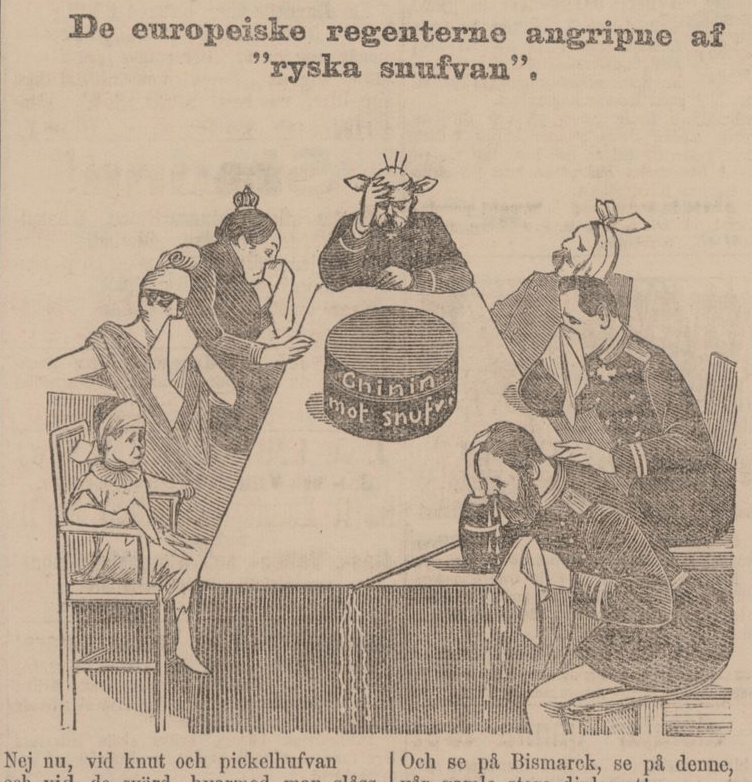

(Box labeled “Quinine against runny nose”)

Not now, by the Russian knout and the Prussian Pickelhaube

and by the swords with which they fight,

we suffer from the Russian snuff

and we in grace cheat ourselves.

All of Europe’s sovereigns

have got a sense of the snuff;

but thrones shall not fall

just for this sudden catarrh…

Then England’s proud mistress

does not go free of the flu,

may Spain’s little king reconsider,

that she also rules over him.

And look at Bismarck, look at him,

he was a grand old diplomat!

He cannot outsmart her,

she grabbed him neatly.

There, in the high courtrooms,

living doctors fall asleep easily;

but behold, she is still awake,

and you do not know her right.

It has been said that she passes so gently:

she pinches, but lightly and softly.

Well, it’s tiny! She cruelly martyrs royal purple.

Yes, the kingdom, it is sick.

(Fäderneslandet, Stockholm, 1889)

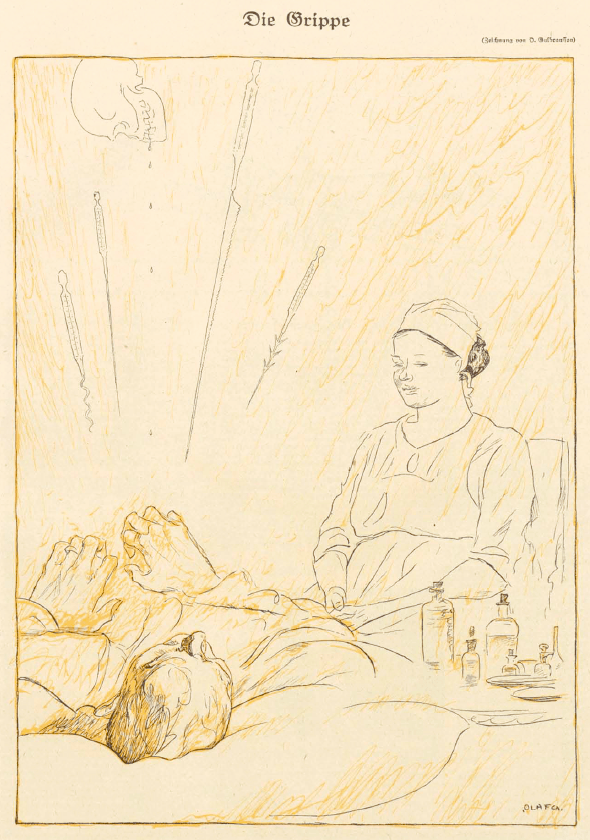

Simplicissimus no. 44 (Munich, 1922)

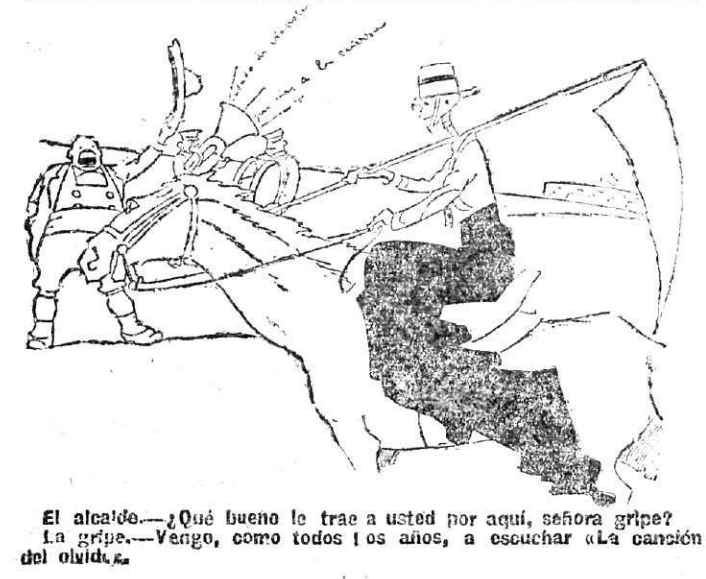

Mayor. “What good brings you here, madame flu?”

The flu. “I come, like I do every year, to listen to The Song of Forgetting.”

(El Mentidero, Madrid, 1919)

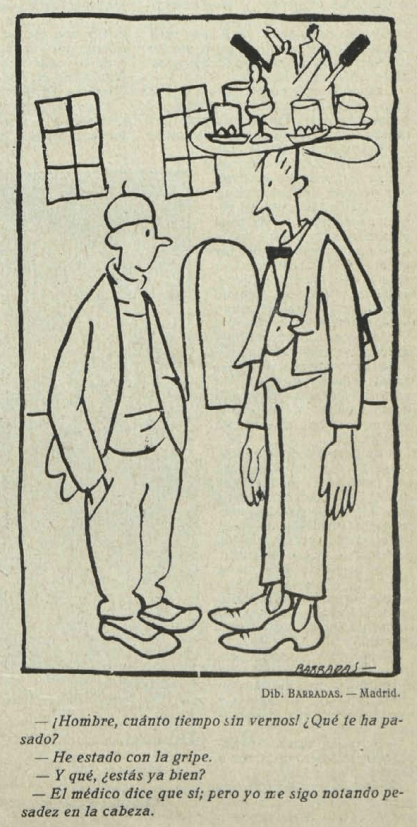

“Man, how long has it been since we saw each other! What’s been happening with you?”

“I’ve been down with the flu.”

“So are you okay?”

“The doctor says yes, but I still feel heaviness in my head.”

(Buen humor, Madrid, 1923)

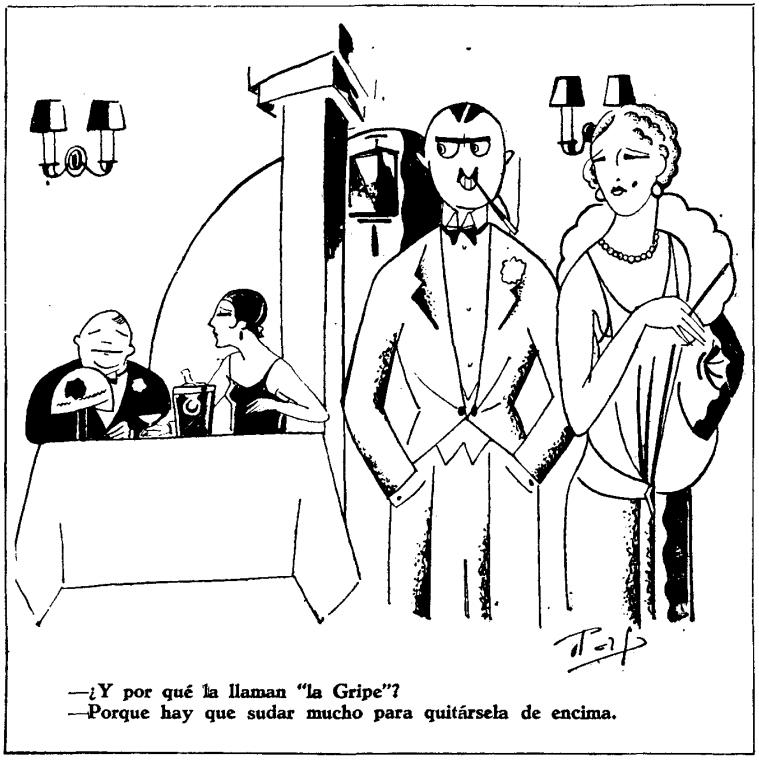

“And why do they call her “the Flu”?”

“Because you have to sweat a lot to get rid of her.”

(Gutiérrez, Madrid, 1931)

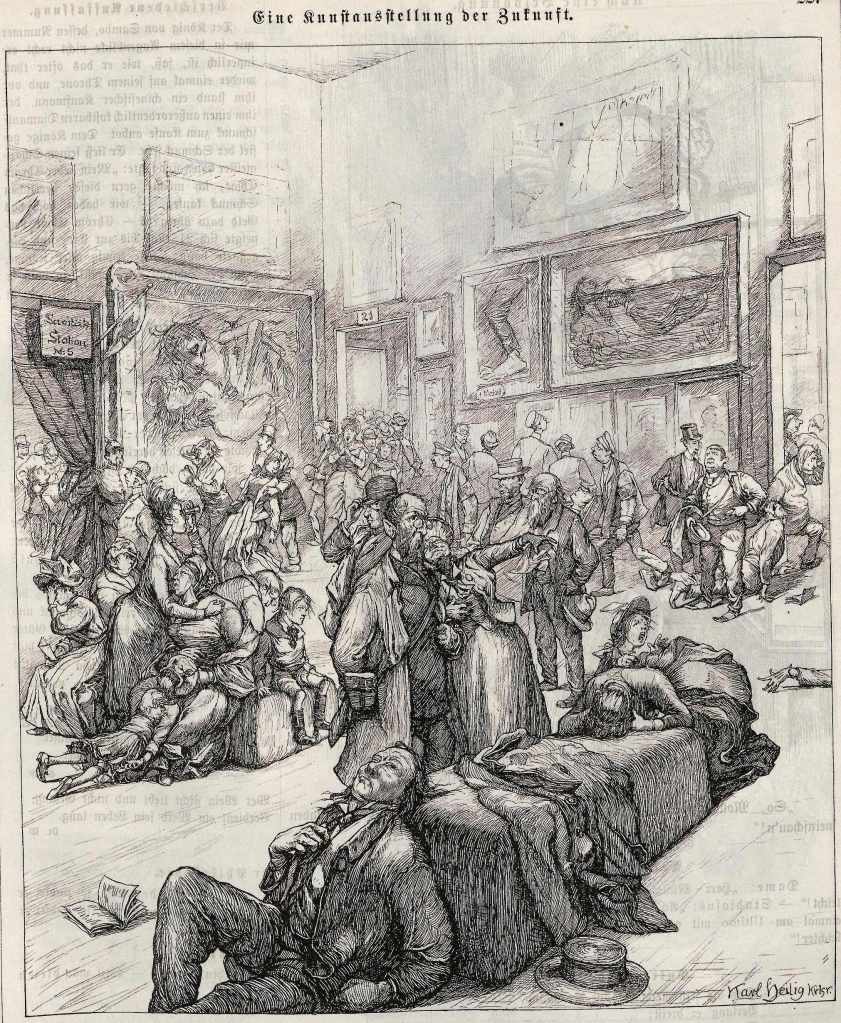

(With a flu epidemic underway late in 1889, this image signaled the duress not only in the grim artworks on the walls and the ailing visitors sprawled around the exhibition space. On the left one can see a sign for “Hygiene Station No. 5,” a deft reminder of our present dilemmas.)

(Fliegende Blätter, Munich, 1889)

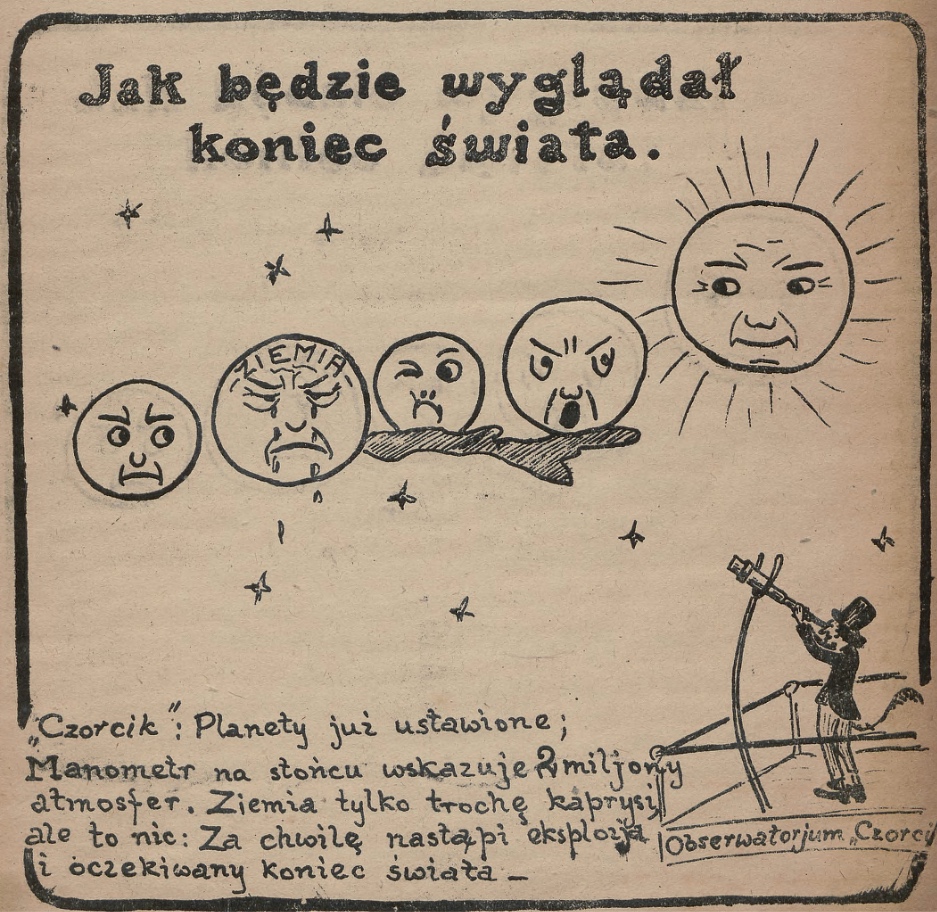

(A sniffly planet earth, as seen from the “Little Devil” Observatory during the second wave of the great flu pandemic.)

The planets are already aligned; the solar pressure gauge shows 2 million atmospheres. The earth is just a little capricious, but that’s nothing: In a moment there will be an explosion and the expected end of the world.

(Czorcik, Piotrków Trybunalski, 1919)

“Please, just hold out your hand!”

(Ulk, Berlin, 1929)

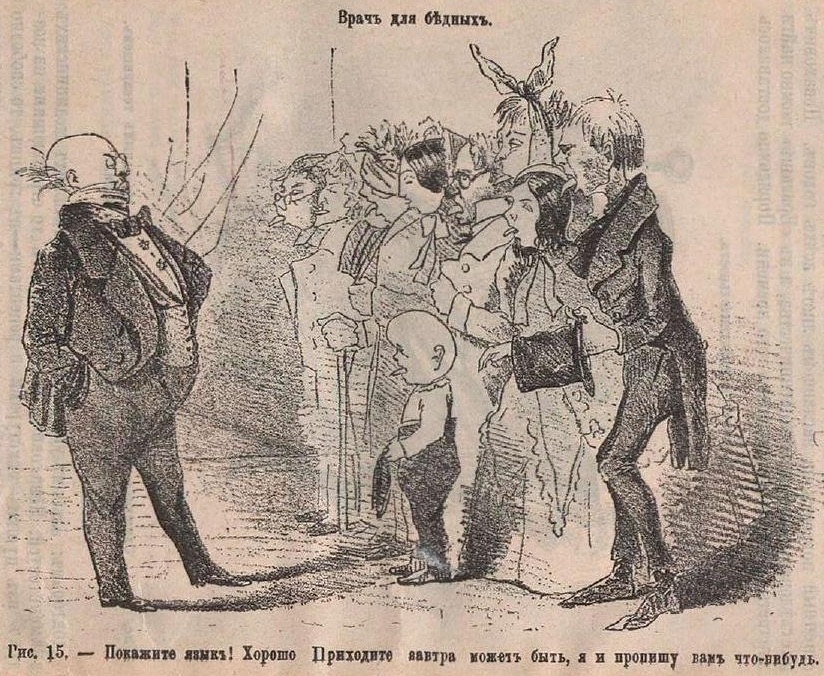

“Stick out your tongue! Fine. Come tomorrow, perhaps I’ll prescribe something for you.”

(Both influenza and cholera were present in St. Petersburg when this was published in one of Russia’s first illustrated satirical journals.)

Mikhail Nevakhovich in Yeralash, c. 1848.

(Reprinted in Aleksandr Shvyrov’s Illustrated History of Caricature, 1903)

With the assistance of a bicycle during the influenza Doctor X managed the 112 visits that he had to make daily to his patients.

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1890)

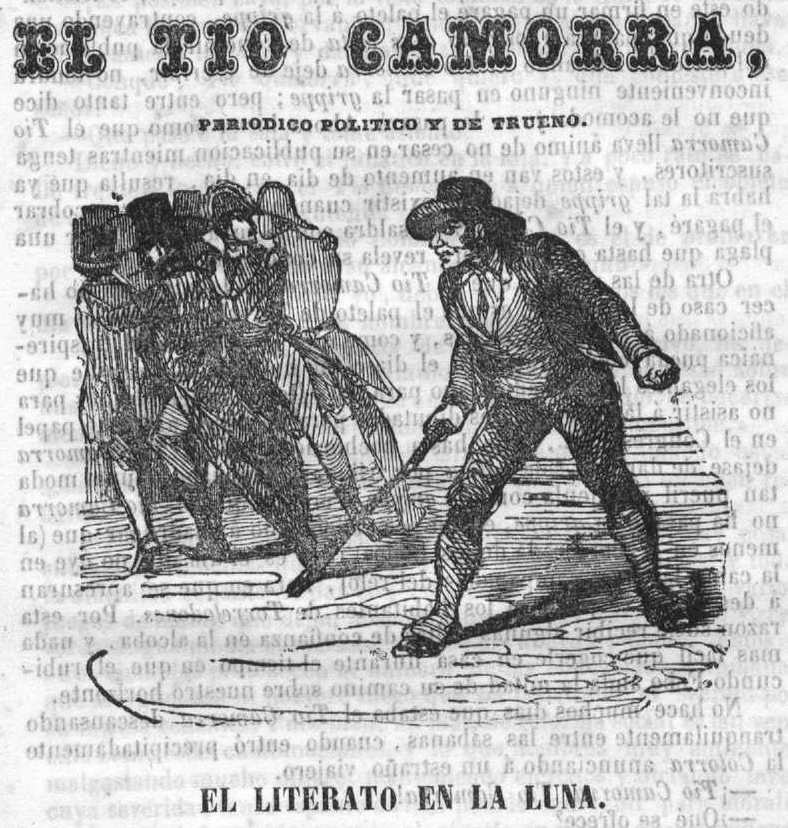

Juan Martinez Villergas launched the Spanish satirical magazine El Tío Camorra (Uncle Trouble) in September 1847, and this plate is featured on the front cover of all the early issues of this short-lived venture, which was closed in July 1848. I lack the expertise to comment on his agendas, but I was struck by the opening passage from the 26 January 1848 issue, several weeks before the revolutionary disturbances that broke out elsewhere in Europe.

“Uncle Trouble has not wanted to catch the flu until now, and has had more than one reason for it. The first and foremost of all is that Uncle Trouble has a great commitment contracted with the Spanish public, and he does not want his beatings to suffer interruption [see image], I do not say for something so mean and petty as having the flu, but for all typhus and cholera around the world. So, then, although the prevailing disease has penetrated the home of the citizen of Torrelodones [i.e., JMV’s alter ego] and resolutely attacked Don Juan de la Pilindrica [his worldly mentor] and the Parrot [another prop in his dialogues], and for other instances that the flu has undertaken to meet with Uncle Trouble, this one has categorically refused to receive it, as he is willing to reject any epidemics that arise while the yokel [meaning Uncle Trouble] pursues the noble and holy mission of enlightening the people and unmasking the public villains. And in order for the flu to desist from its reckless endeavor, it was necessary to reach a compromise in the most prudent way possible, which consisted of the yokel signing a promissory note to the flu, contracting a debt that will be paid within eight days after the publication is completed. When Uncle Trouble stops writing, there will be no problem for anyone to get the flu; but meanwhile he says that it does not suit him and he will not get it. Having said that, as Uncle Trouble has the courage to not stop publishing as long as he has subscribers, and these are increasing from day to day, it turns out that the flu will no longer exist when he wants to come to collect the bill, and Uncle Trouble will get away with not getting a plague that even in name [“la grippe”] reveals his French condition.

Another reason that Uncle Trouble has had for ignoring the flu is that the Torrelodones yokel is not very fond of following fashions, and because the trans-Pyrenean disease can be considered in the day as a bad fashion that the elegant types have used to put on airs, the employees not to go to the office, the deputies not to play a sad role in Congress, etc., it would be even embarrassing for Uncle Trouble to stop giving a single beating for paying homage to a fashion as childish and ridiculous as the flu. But although Uncle Trouble has not had the flu, he is so little fond of getting up early that (at least in the cold season) rare is the day that he does not hear the twelve chimes of the clock in bed, time in which the other inhabitants of Torrelodones hurry to empty the cooking pot. For this reason, he usually receives some trustworthy visitors in the bedroom, and nothing is easier than to catch him at home during the time when the ruddy Phoebus walks halfway over our horizon.”

(El Tio Camorra, Madrid, 1848)