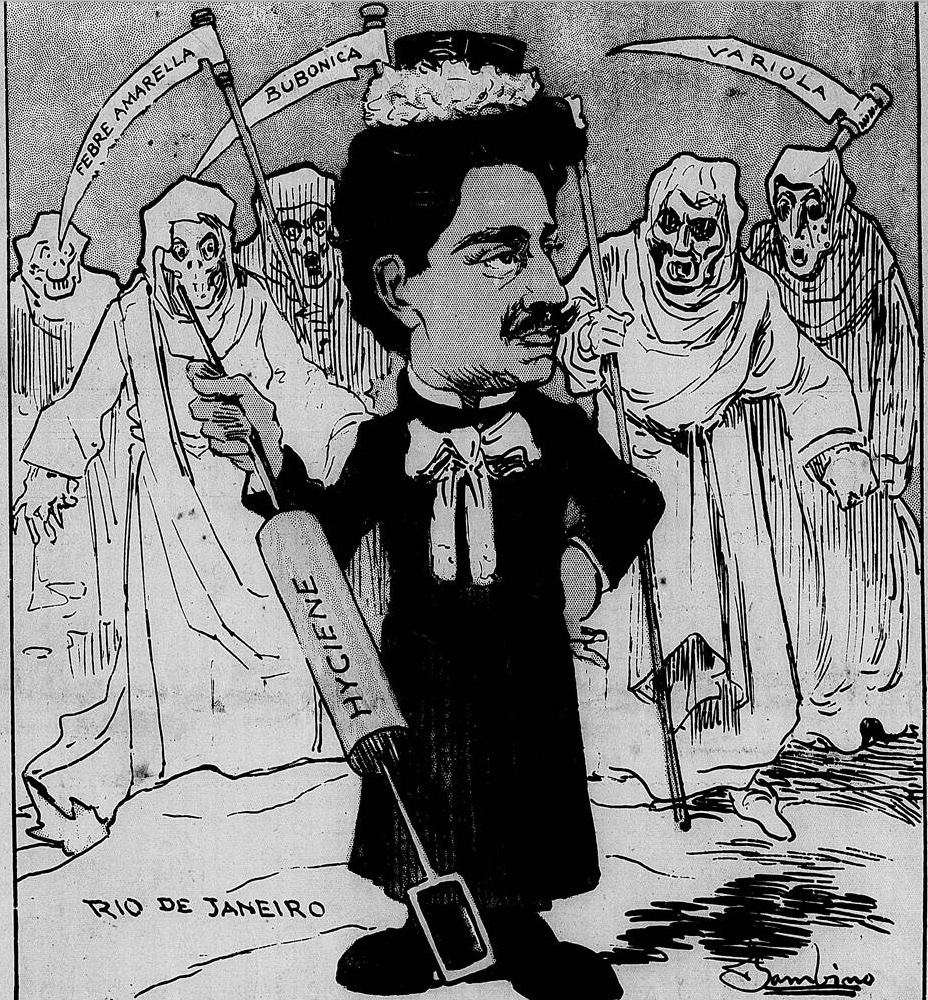

“I’m spreading rumors that plague and anthrax are raging in the vicinity of our dacha.”

“What in the world for?”

“It’s very simple: I’ll be spared the onslaught of dacha guests!”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1907)

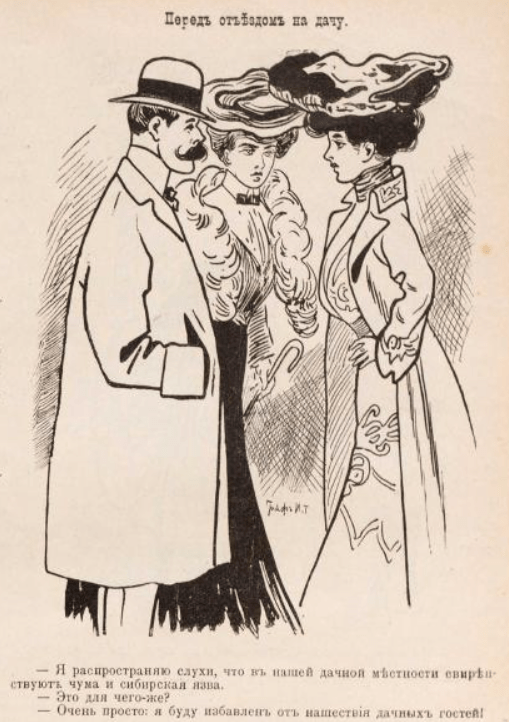

“I’m spreading rumors that plague and anthrax are raging in the vicinity of our dacha.”

“What in the world for?”

“It’s very simple: I’ll be spared the onslaught of dacha guests!”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1907)

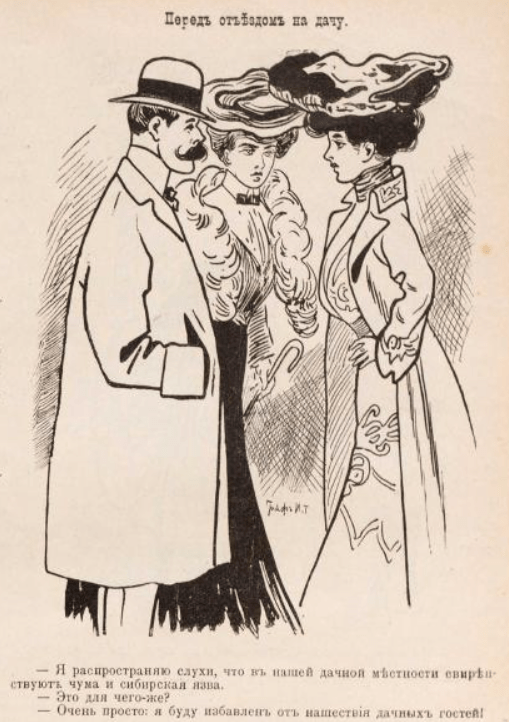

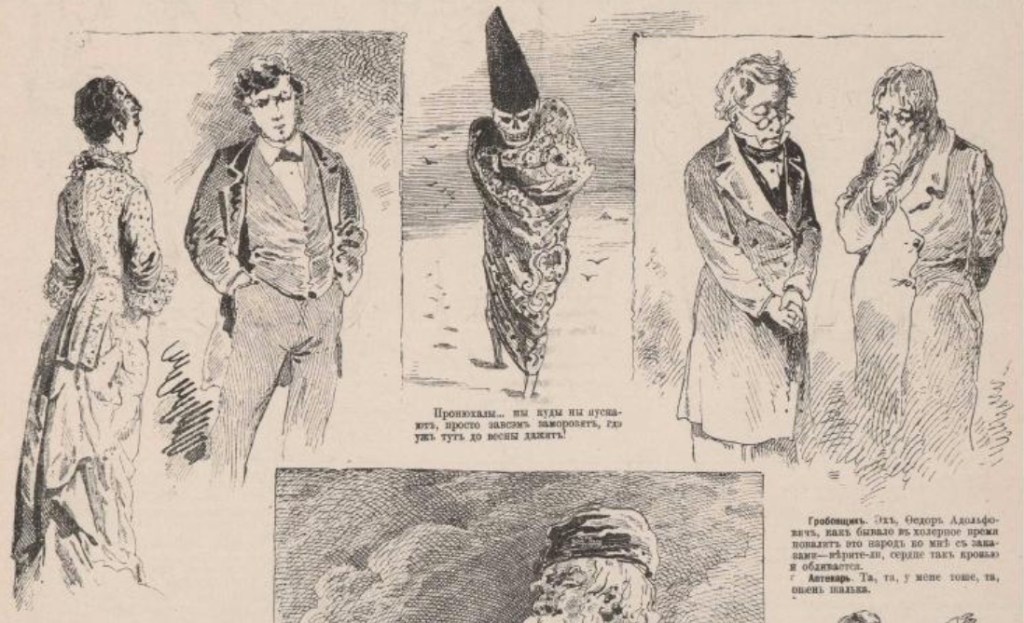

(Strekoza, St. Petersburg, 1879)

(Some very unpleasant metaphors on display here.)

(Auction; bank offices)

This kind of plague is widely dispersed in Europe; there are not yet any remedies against it.

Left: “Oh! I’m terribly afraid of plague!”

“We ought to send you to some kind of Vetlianka [in the Astrakhan region, where the plague outbreak originated in 1878] like I have at home, it would be cleaner than the Astrakhan one…”

“How’s that?”

“It’s very simple: a wife is cholera, a mother-in-law is worse than plague! You’ll get along fine there.”

Center: “They sniffed us out… they don’t let us anywhere, just completely freeze us, where to live until spring!”

Right: Undertaker: “Eh, Fedor Adolfovich, just like when there was cholera, people are overwhelming me with orders, believe me, my heart is just overflowing.”

Pharmacist [of German heritage]: “Ja, ja, same with me, ja, ist a pity.”

Left: (Fresh groceries, imported goods) “We’ve just gotten in fresh, low-salt Astrakhan caviar and sweet Astrakhan grapes, now being sold at extremely low prices!”

Center: “It’s happened! Freeze the guests — now they’re freezing… Maybe now we can handle it.”

Right: “How are you not afraid of buying old things? Who knows how long until they spoil!”

“In a new frock coat you will sooner get sick [“get the plague”] dropping not ten, but forty-five rubles.”

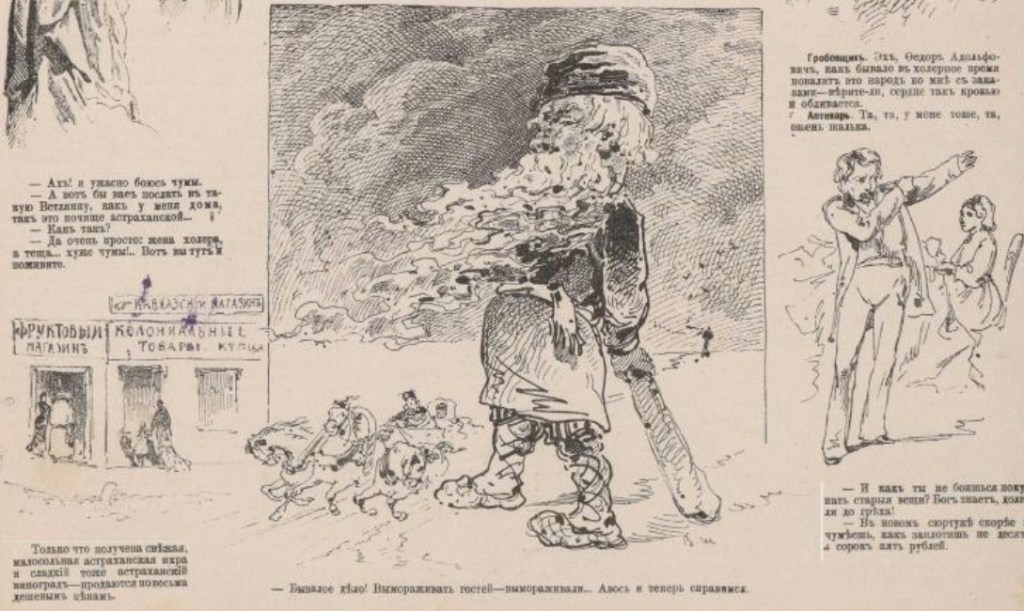

Son: “Papa, what’s plague? Is it pestering us?”

Father: “It’s your mama.”

Mother: “Will you leave me alone, you obnoxious brute?!”

Father: “Leave alone! There’s the first instance of the unobtrusiveness of the plague.”

(Strekoza, St. Petersburg, 1879)

(Notwithstanding the flatfooted sexism of this cartoon, there was a recurrence of actual plague in Russia at this time.)

“What’s going on, did your husband get the plague?”

“Yes, he just got back from Serpukhov.”

“Oh, I forgot that the plague there is in the cattle.”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1885)

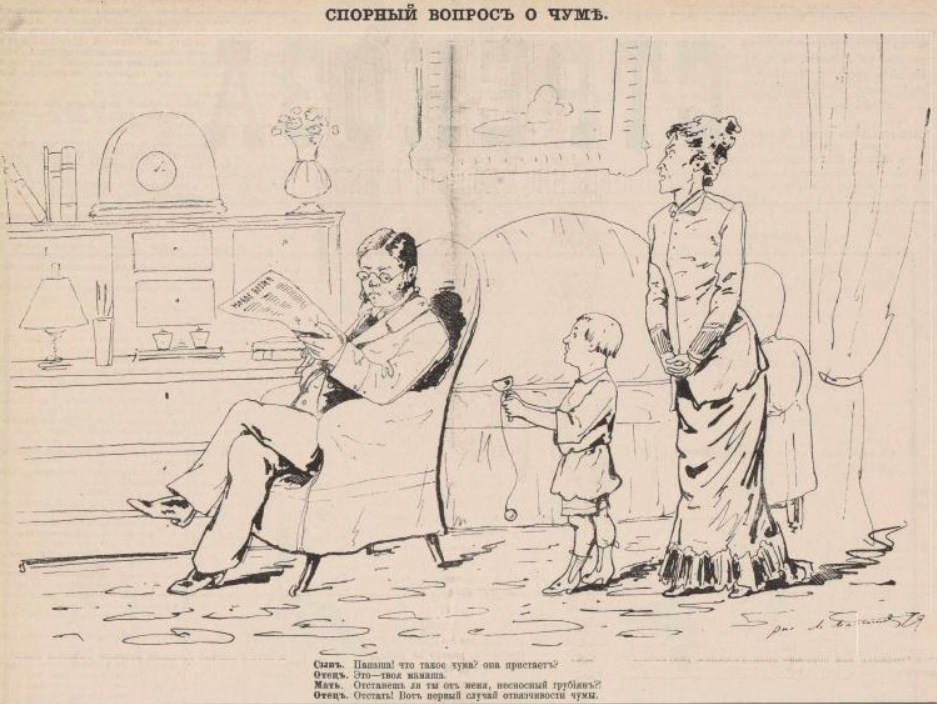

“Your article isn’t suitable. If you had written something about plague, then it would be another matter.”

“But how can I write that? I haven’t been in those locales.”

“Then what’s your imagination for?”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1879)

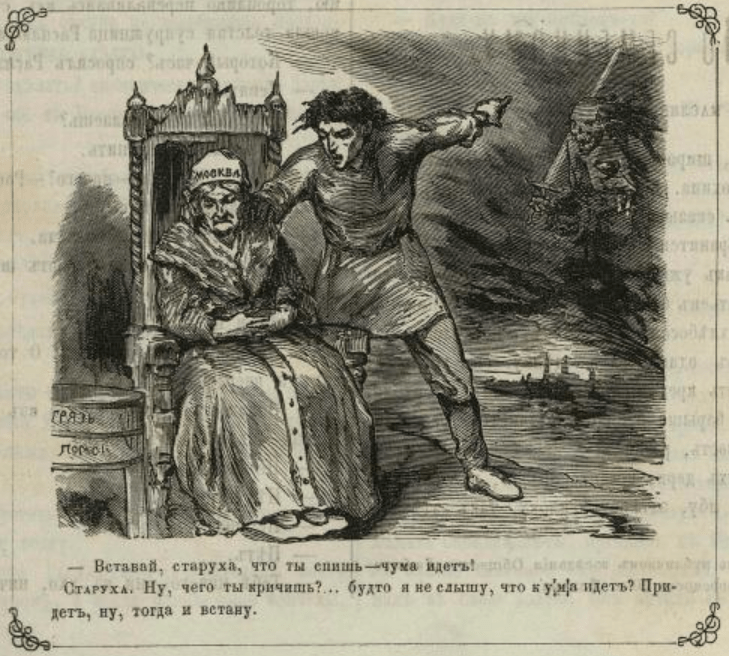

“Get up, old lady [Moscow], why are you sleeping? The plague is coming!”

Old lady: “Why are you shouting? As if I don’t hear the plague coming? When it arrives, I’ll get up.”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1879)

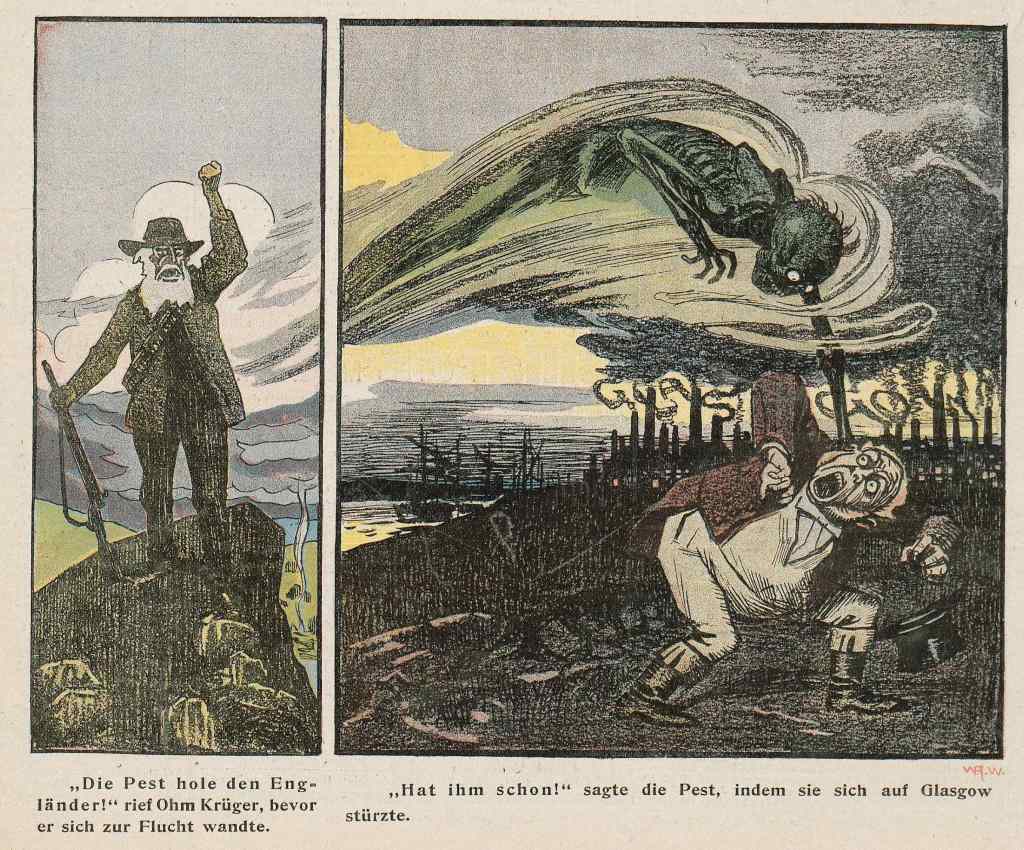

“The plague take all the Englanders!” cried Uncle Krüger before fleeing.

“I already have!” said the plague, pouncing on Glasgow.

(Lustige Blätter, Berlin, 1900)

(Paul Kruger was the president of the South African Republic during the Boer War against the British. Glasgow was suffering from a small outbreak of plague at the time.)

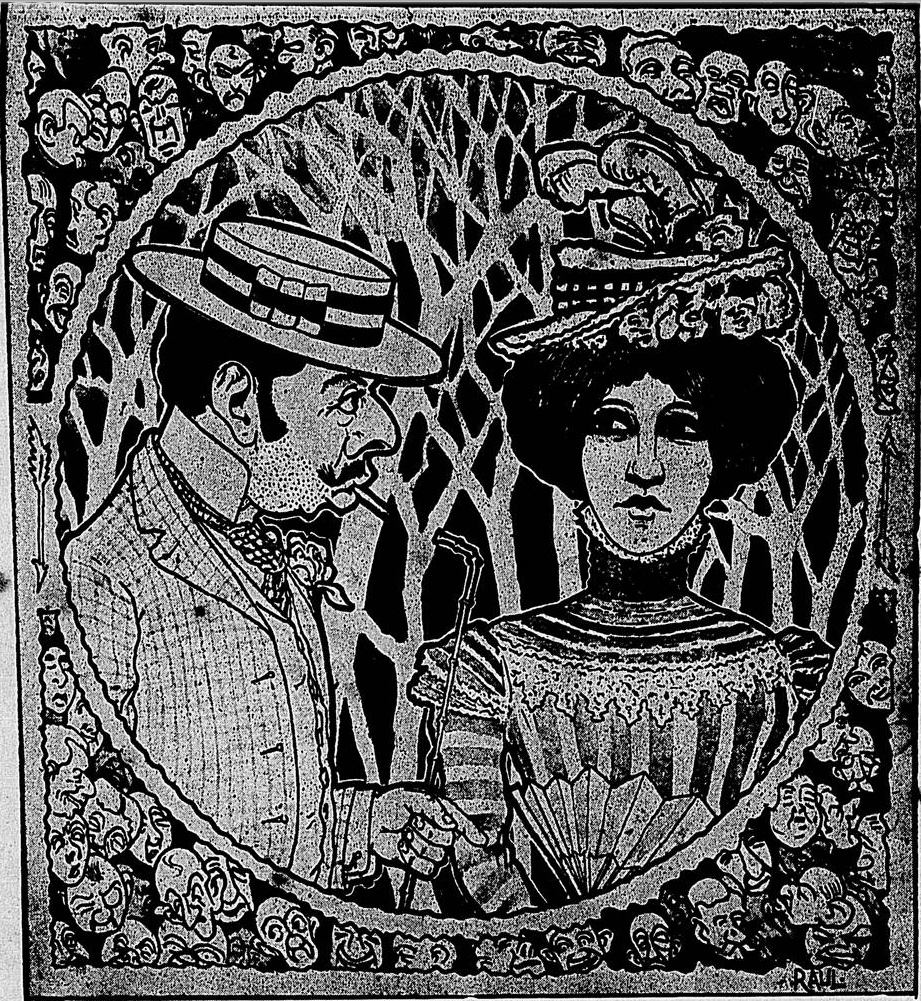

“It is frightening, my dear; it seems that the plague is approaching us.”

“Your mother is coming to see us?”

(Le Monde comique, Paris, 1879)

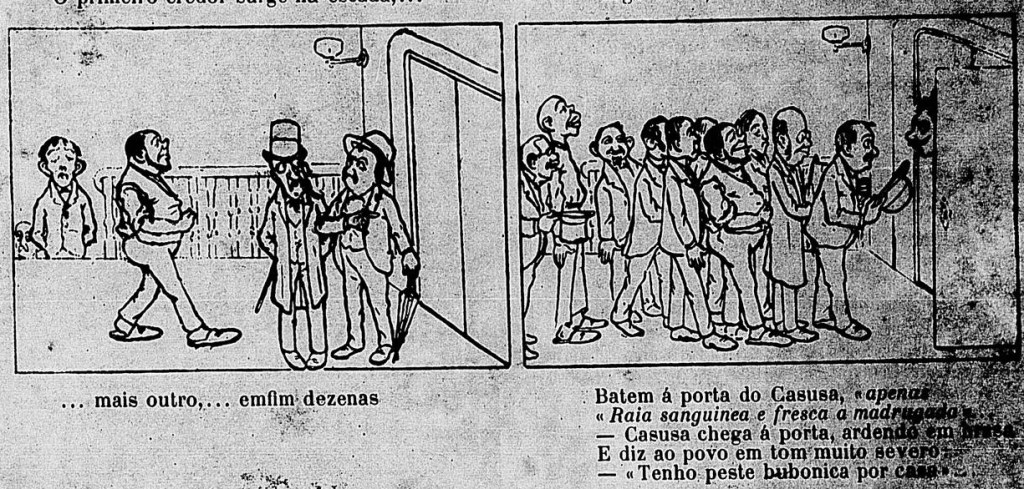

(La Revista da semana, Rio de Janeiro, 1900) (While I can’t capture the idiom, the point of the cartoon is clear. There are similar flu-related cartoons in Czech and Hungarian versions.)

The first creditor appears on the stairs,…

Another comes up, and another…

…yet another,… finally dozens

They knock on Casusa’s door, “a bloody fresh band at dawn.”

Casusa arrives at the door, burning in [illegible]. And he says to the people in a very stern tone, “I have bubonic plague around the house.”

“Plague?! Jesus! We’ve got to leave now!!”

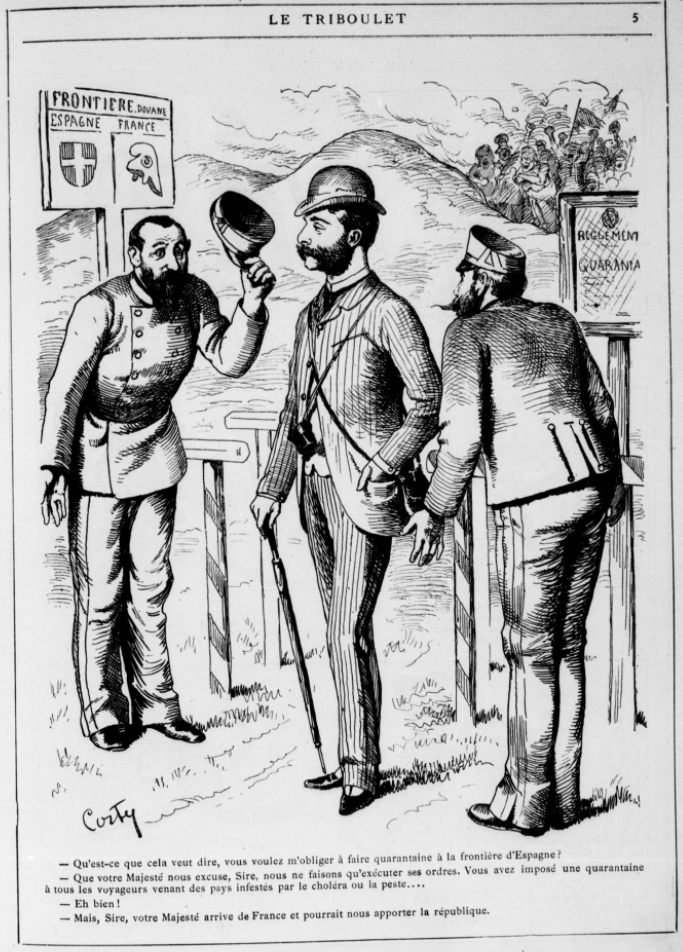

“What do you mean, you want to force me to quarantine at the Spanish border?”

“Your majesty will pardon us, Sire, we are only carrying out your orders. You have imposed a quarantine on all travelers coming from countries infested by cholera or plague…”

“Well!”

“But, Sire, your Majesty is coming from France and could bring us the republic.”

(Le Triboulet, Paris, 1883)

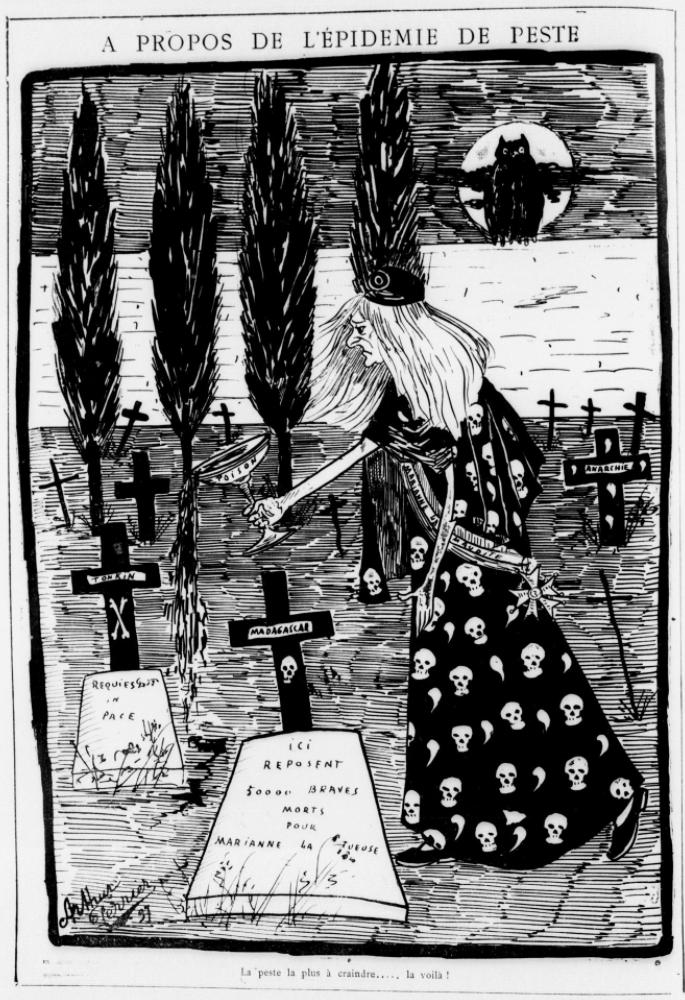

“The plague to fear the most… here it is!”

(The woman’s sash reads “Marianne the cursed,” and given the tombstones, this seems like a gesture toward the costs of French colonialism. In 1897 there was news of an outbreak of plague in India, sparking fears that it would make an appearance in Europe. The tenth international sanitary conference was held in Venice that same year, devoted to discussion of bubonic plague.)

(Le Triboulet, Paris, 1897)

“Improved six-barreled flea-thrower with a refuting double-barreled trailer.”

Ballistic cannisters labeled “plague,” “typhus,” “cholera.”

(American Secretary of State Dean Acheson and UN Secretary-General Trygve Lie are doing the refuting.)

(Krokodil, Moscow, 1952)

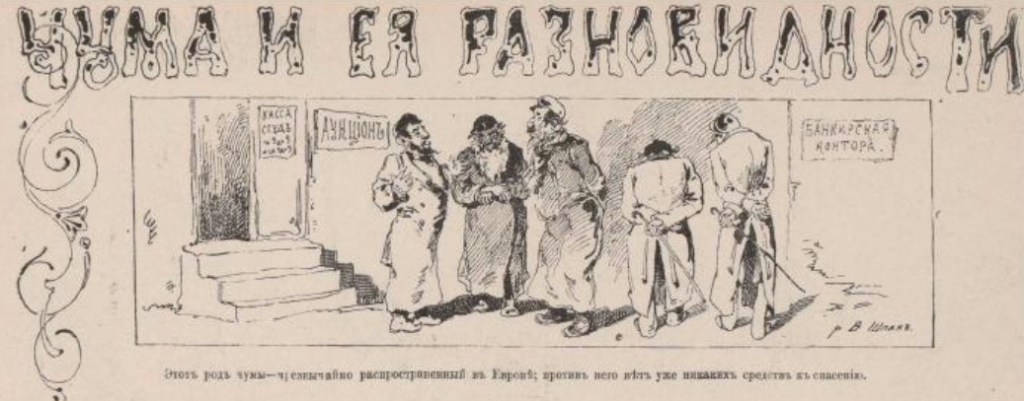

“This year we have over 60 doctors in medicine…”

“Oh my! We will have bubonic plague for a long time.”

(Revista da Semana, Rio de Janeiro, 1900)

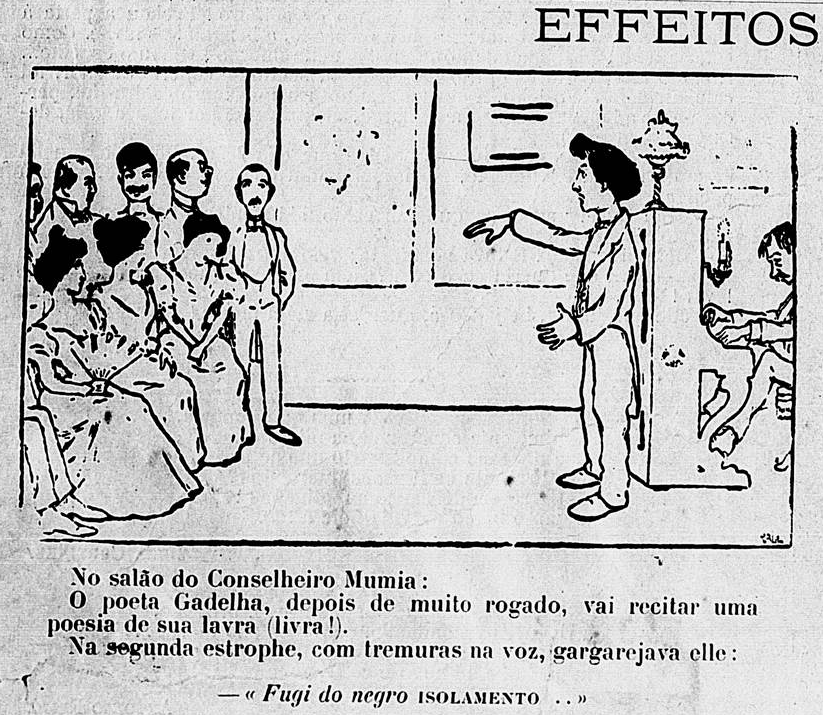

At the salon of Counselor Mumia:

The poet Gadelha, after many requests, will recite a poem of his own (free!).

In the second stanza, with tremors in her voice, she would gargle at him:

“I escaped the black ISOLATION.”

“Isolation?!” (General stampede)

(Revista da Semana, Rio de Janeiro, 1900)

Yellow fever, plague, and smallpox stand arrayed in chorus against public health in the person of Oswaldo Cruz, the biologist and government official most closely identified with Brazil’s efforts to introduce obligatory vaccination.

(choir in the background) “If it weren’t for you getting in the way of our sinister steps, what a good harvest we would have made during the visit of the American fleet!”

(Revista da Semana, Rio de Janeiro, 1908) (Compare Oswaldo Cruz’s iconic status in O Malho.)