(Punch, London, 1918)

(Punch, London, 1918)

…against the further spread of cholera. (“Denial sprays” are being applied against cholera.)

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1910)

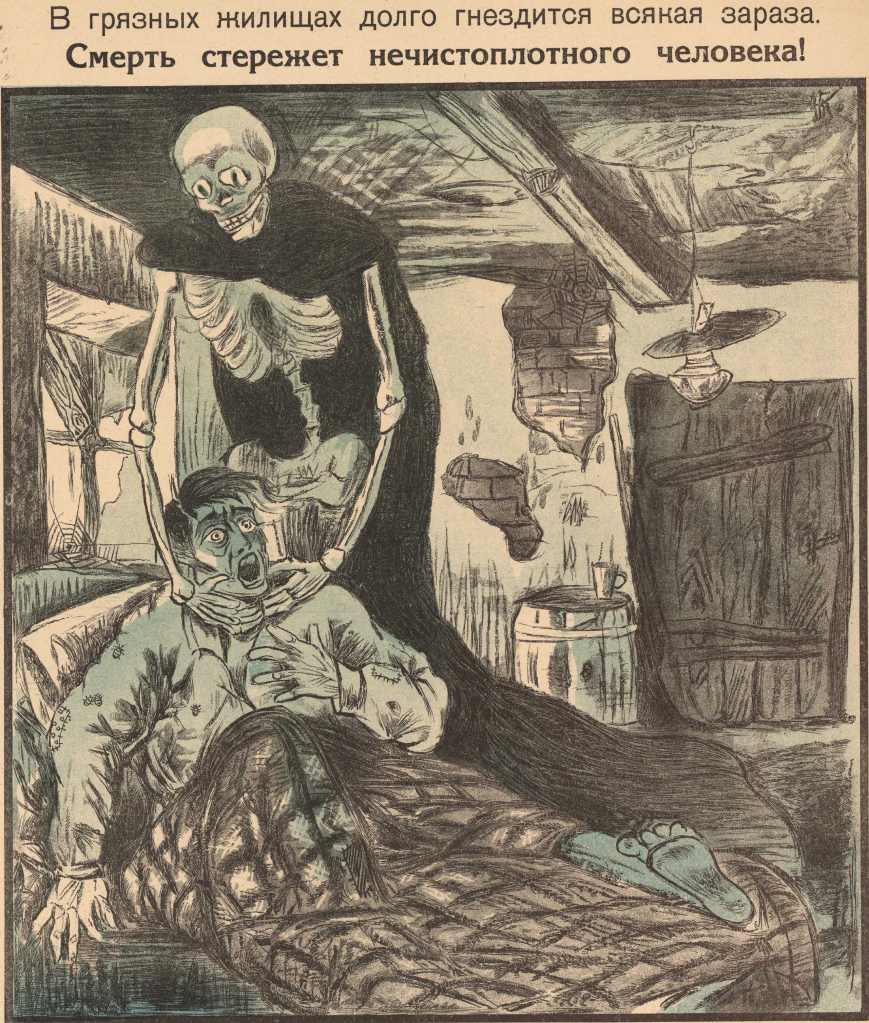

“In filthy residences any contagion can take root for a long time.” “Filth and uncleanliness are one of most important causes of our illnesses.” Detail from an educational poster by the Ukrainian People’s Commissariat of Health, 1920. (Russian State Library)

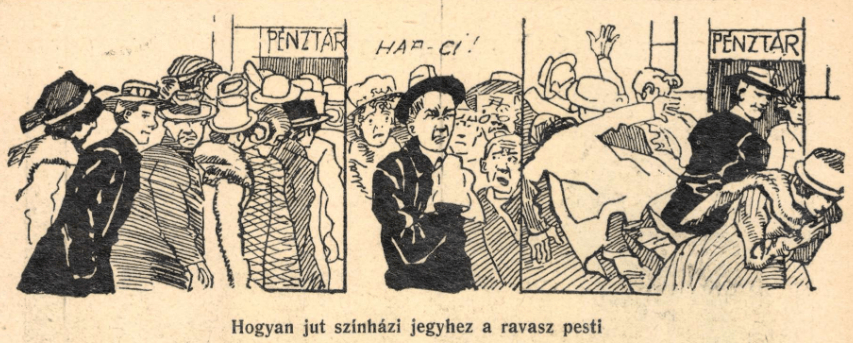

“How a cunning Pest resident gets his hands on a theater ticket.” (Man sneezes at the ticket office and the crowd scatters. This was at the height of the influenza epidemic.)

(Borsszem Jankó, Budapest, 1918)

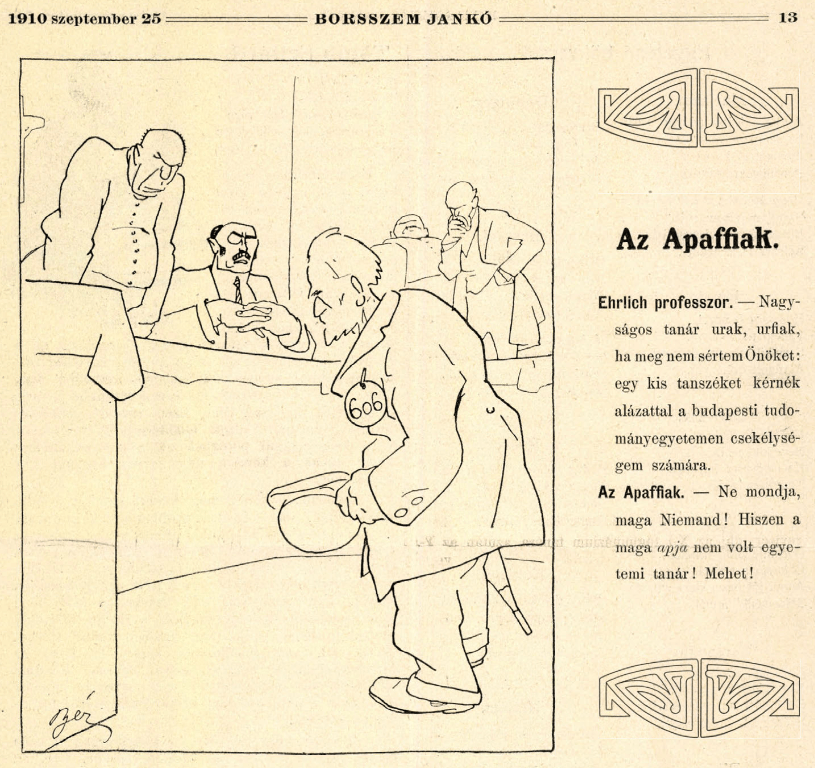

This is a bit obscure, but it was published at the height of bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich’s fame in 1910, when he was offering a cure for syphilis (“606”), and it seems to poke fun at the insularity of the academic appointment process. (It cannot have been coincidental that Ehrlich was Jewish. Though a disproportionately high percentage of physicians in Hungary were Jewish, access to university teaching positions remained limited.)

Professor Ehrlich: “Honorable colleagues & sons, if I do not offend you: I would respectfully like to request a small academic chair at the University of Budapest for your humble servant.”

Sons: “You don’t say, Mr. Nobody! After all, your father was not a university professor! You may go!”

(Borsszem Jankó, Budapest, 1910)

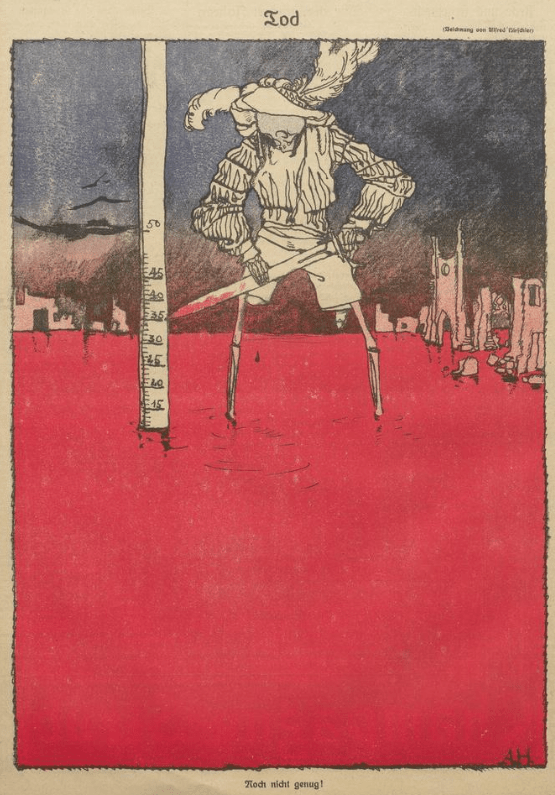

“Not enough yet!” (From the Spanish attire we may assume that Death was hoping for influenza to contribute its part.)

(Nebelspalter, Zurich, 1918)

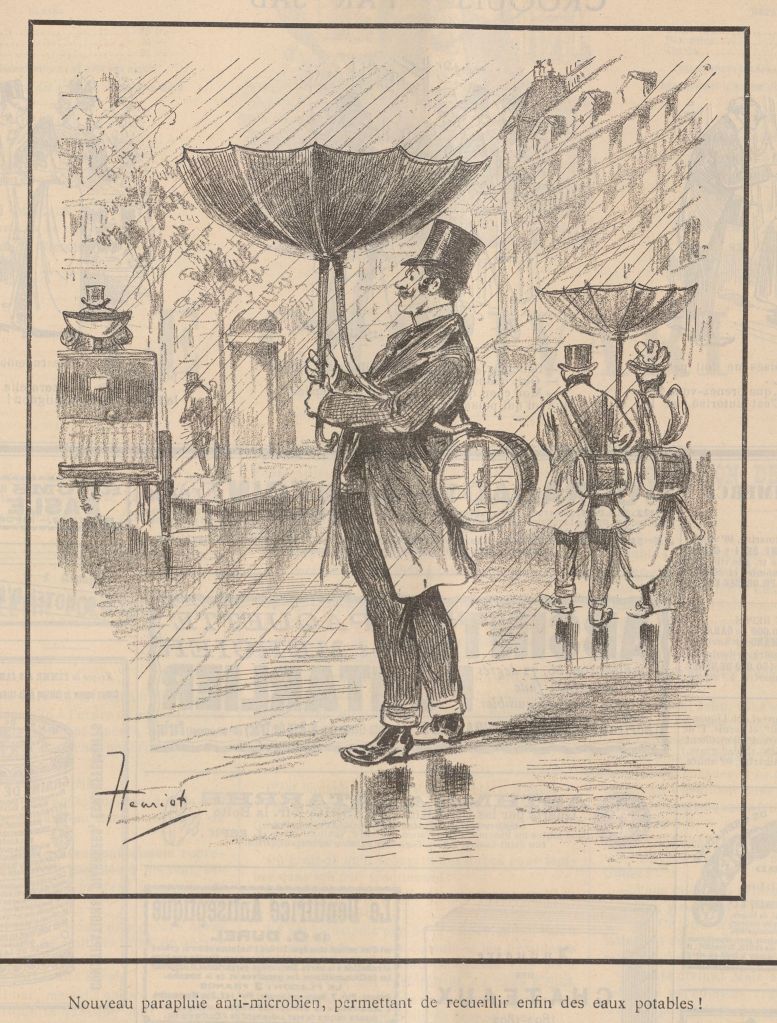

New antimicrobial umbrella that finally lets you collect potable water!

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1892)

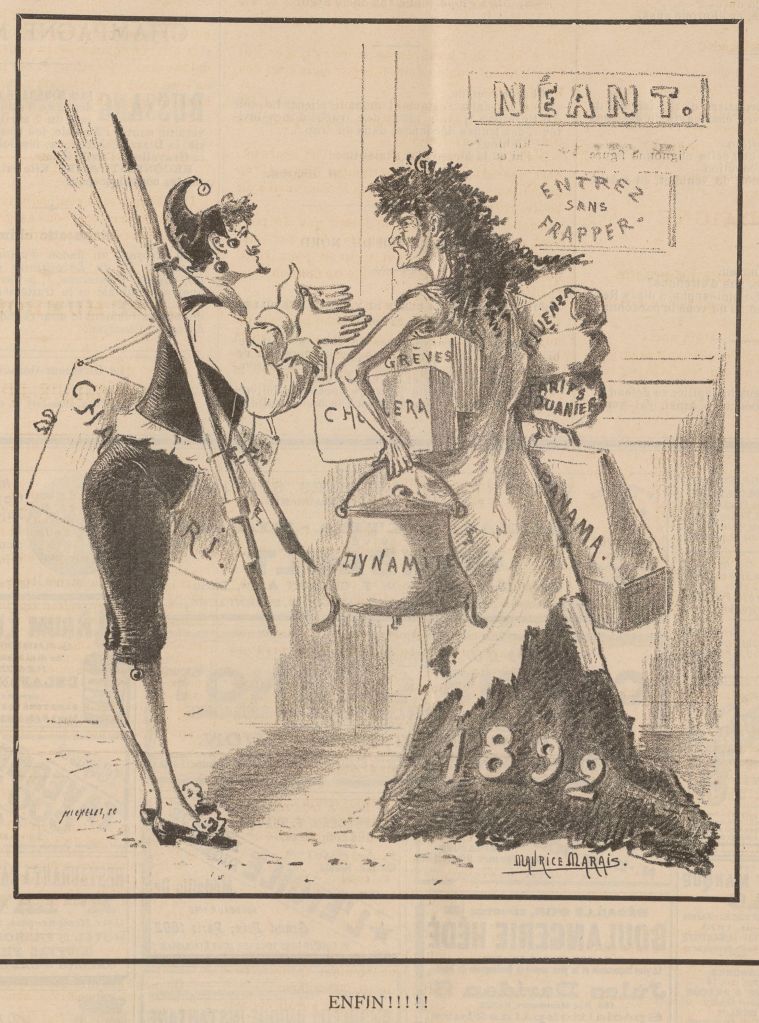

The year 1892 finally exits the store carrying her acquisitions: dynamite, cholera, strikes, influenza, tariffs, and the Panama Canal scandal.

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1892)

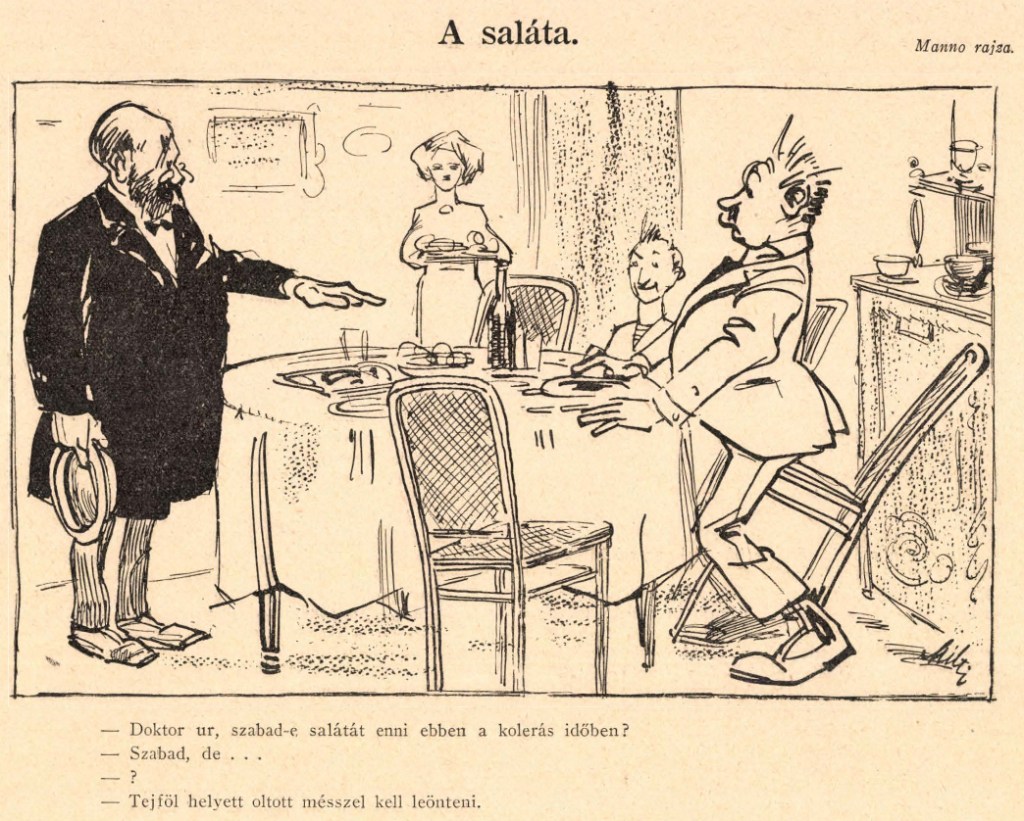

“Doctor, is it OK to eat salad in a time of cholera?”

“Yes, but…”

“What?”

“Instead of pouring sour cream on it, you should use slaked lime.”

(Kakas Márton, Budapest, 1910) (Arcanum)

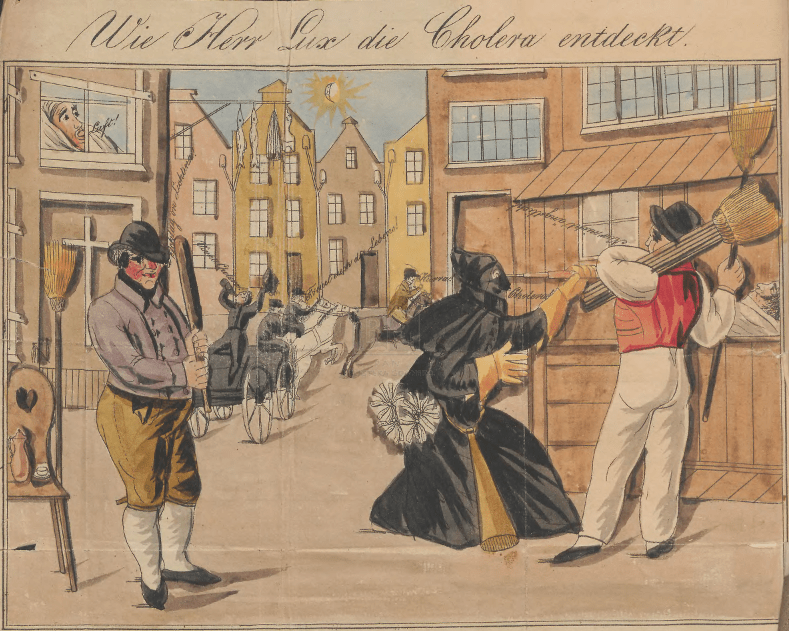

Frontispiece from a booklet published during the 1831 cholera epidemic. The man in the window (upper left) cries “Air!” The man on the street below him wants to beat something that has “light” as the root, but I can’t make out the final letters. (A Dutchism?) The woman in black enjoying her alcohol is crying “Long live cholera!” The men on horses are calling on everyone to enjoy life. The man in the red vest is saying “No need for concern,” while the well-protected Mr. Lux in black hood and gown has identified cholera with his telescope. Despite the didactic title, this is actually a booklet of light verse addressed to cholera: “And should you head off track to us, then you will soon know: We’ll remain strong, but you are weak!”

Wilhelm Schumacher, Most comprehensible and reliable instructions on the dangerous, plague-like disease cholera morbus. Provided with a recipe that teaches the safest means of protection against cholera, and surpasses and makes superfluous all the books that have already appeared and may still appear. According to the main medical results of experiences carefully compiled in India , Persia, Russia and Poland (Danzig, n.d. [1831]).

Kikeriki: “Look, look, now the cholera patients won’t be purged at all!”

(Doctor heading towards cholera ward with syringe labeled “denial shots.”)

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1911)

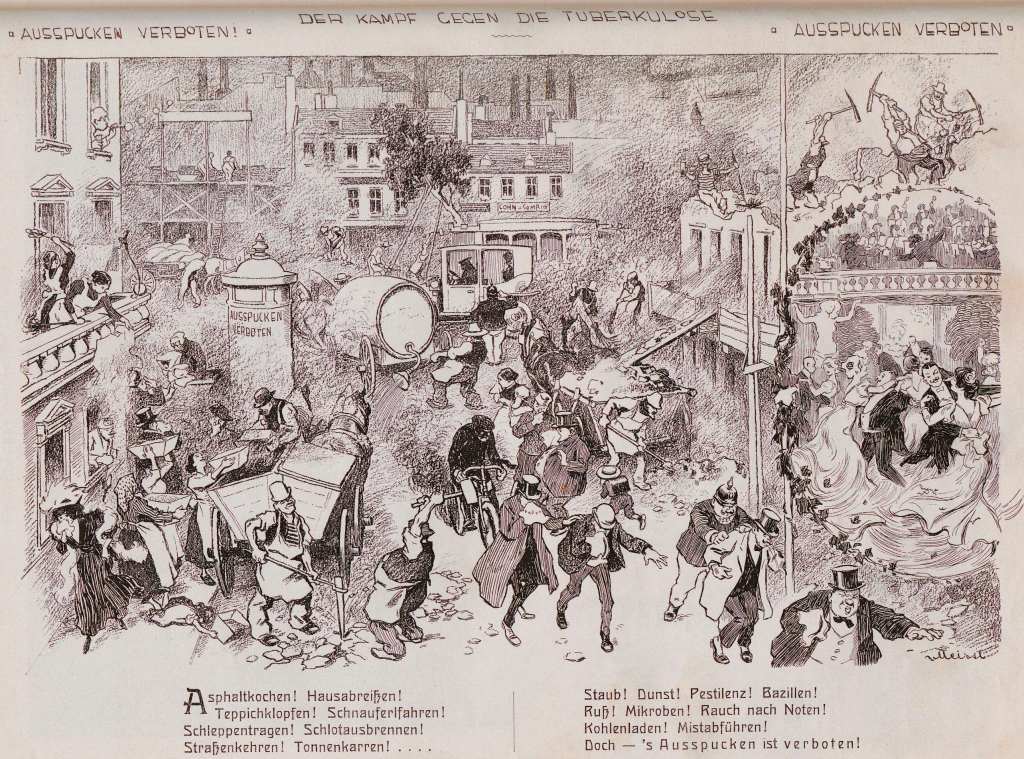

Spitting is not permitted!

Cooking asphalt! Demolishing houses!

Beating carpets! Driving a car!

Dragging a train! Chimney cleaning!

Street sweeping! Barrel carting!

Dust! Fumes! Pestilence! Bacteria!

Rust! Microbes! Smoking at the break!

Loading coal! Carting away manure!

But — spitting is not permitted!

(Fliegende Blätter, Munich, 1908)

Professor: “… It is not rare for diseases to exist in the human body which go entirely unmarked for years at a time.”

(after the lecture)

“Why are you so quiet today, dear Flora?”

“Oh, dear Mama, I will die soon, I just know it, I have consumption!”

“But why would you get such a strange idea, you’ve never complained about any pains!”

Flora (crying): “That’s just it, I don’t feel anything at all!”

(Fliegende Blätter, Munich, 1873)

(Nebelspalter, Zurich, 1918)

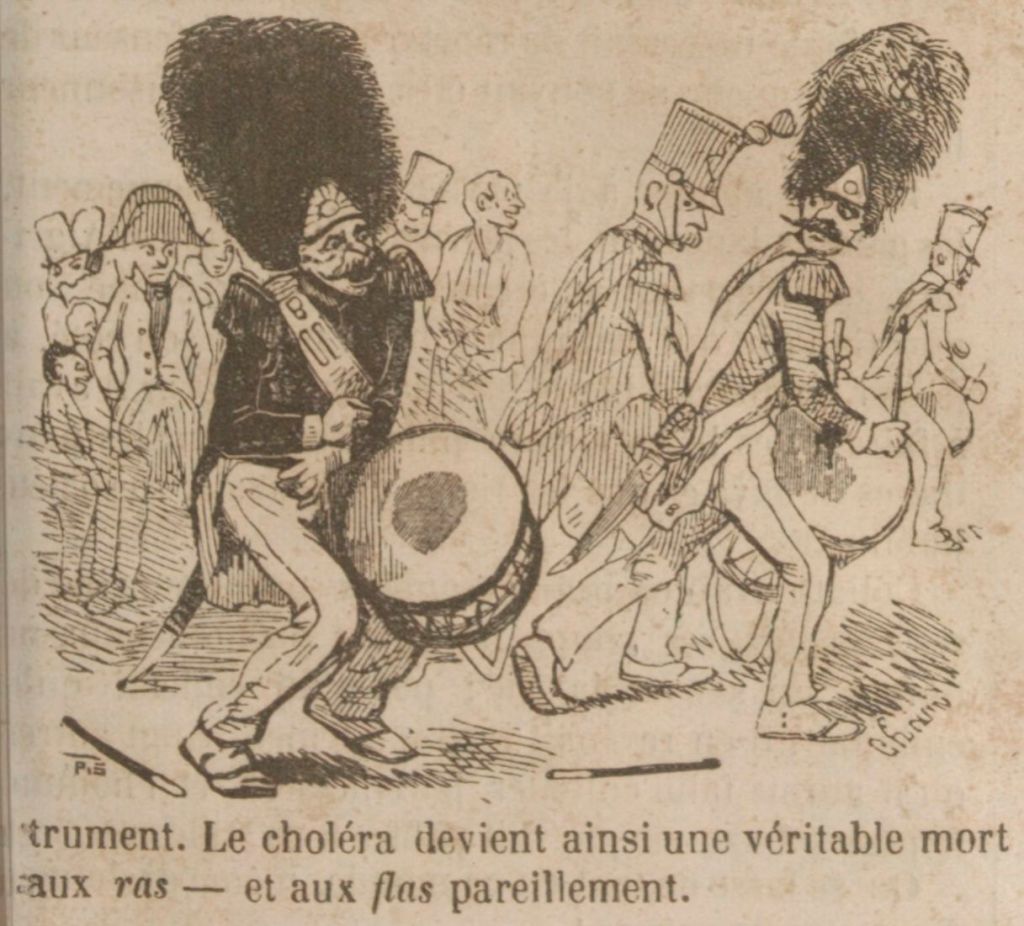

I’m overreaching here, but I find this connection oddly amusing. First: Eugène Sue began publishing the serial novel The Wandering Jew in 1844, and it enjoyed great popularity in Paris. Although it made reference to the legendary figure who taunted Jesus on the way to crucifixion, the central thrust of the novel, set in 1831, was rather more anti-clerical. The intrigues of a Jesuit named Rodin figure strongly, while epidemic cholera drives goodly portions of the plot. Eventually Rodin himself is seized with the cholera, and Sue narrates a scene of carts filled with coffins clattering down city streets at night, invoking “the joyous strains of the grave diggers; public-houses had sprung up in the neighborhood of the churchyards, and the drivers of the dead, when they had “set down their customers,” as they jocosely expressed themselves, enriched with their unusual gratuities, feasted and made merry like lords; dawn often found them with a glass in their hands, and a jest on their lips; and, strange to say, among these funeral satellites, who breathed the very atmosphere of the disease, the mortality was scarcely perceptible.” The “dregs of the Paris mob” would gather near the main hospital and mock the vain ministrations of the physicians. As things become unruly, drums are heard in the distance, signaling a call to arms to quash sedition in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. When the drummers emerge from under an archway, an older one collapses, himself the sudden victim of cholera. There are shouts that he has been poisoned, having drunk from a fountain en route, and the expiring drummer is carried away to cries of “Make way for the corpse!” Not long thereafter, “The cholera masquerade” is proclaimed, “one of those episodes combining buffoonery with terror, which marked the period when the pestilence was on the increase…”

Second: the echo of satire. The French satirical magazine Le Charivari appears to have run its own version of “The wandering Jew” in 1845, where we find this scene featuring Rondin (not Rodin) from a chapter entitled “The cholera”: “The colics of Rondin were only the prelude to other, much more general colics, the cholera is definitely in Paris, as well as the death-eaters who earn mad money, who dance a polka of jubilation. The more Parisians rub their stomachs, the more they rub their hands! But what do you want, for these officials the Chemin du Père-Lachaise [along the largest cemetery in Paris] is the road to fortune!

Cholera has become so universal that it no longer respects anything and it even attacks the drums of the National Guard, which ordinarily still fears so much for its skin!

More than one drummer, while striking the beat, cannot finish the tune he has started on his instrument. Cholera has thus become a veritable death on the rim – and likewise on the flam.”

But in this version, when a “society of tramps” organizes the cholera masquerade, they are joined in their rowdy refrains by the Parisian medical faculty.

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1845)

OK, that was a long walk.