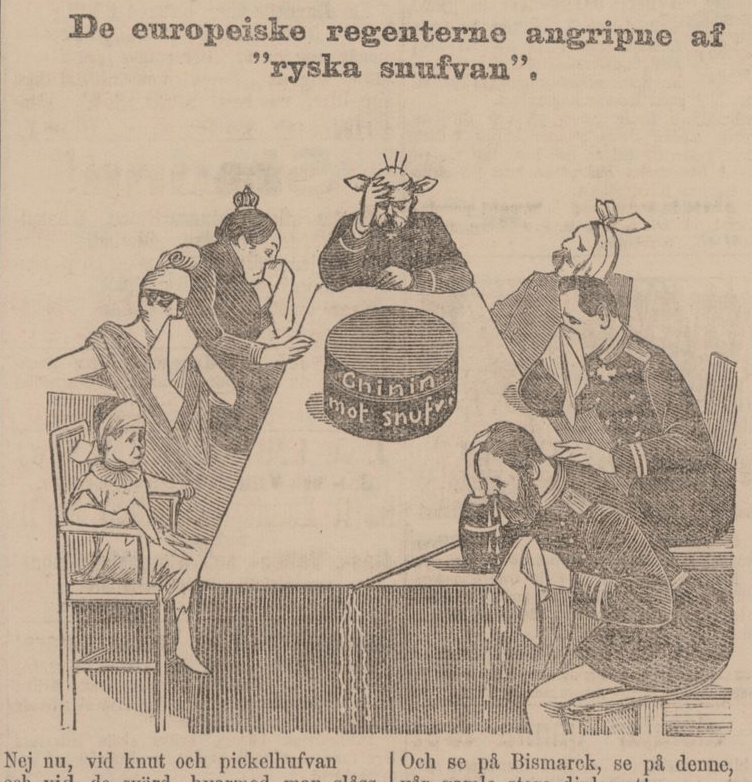

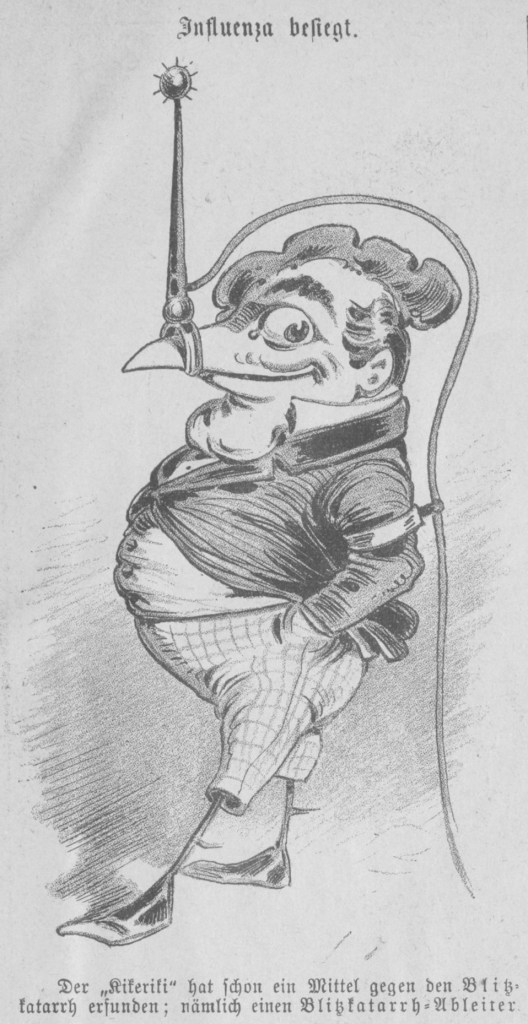

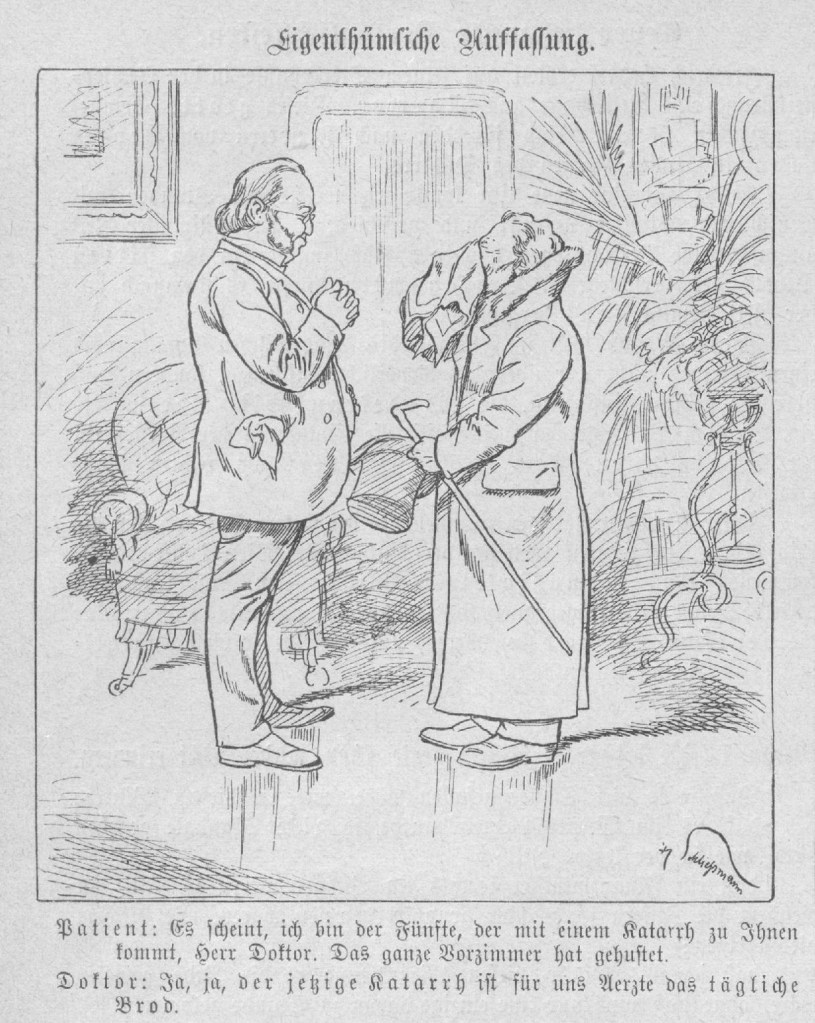

(Box labeled “Quinine against runny nose”)

Not now, by the Russian knout and the Prussian Pickelhaube

and by the swords with which they fight,

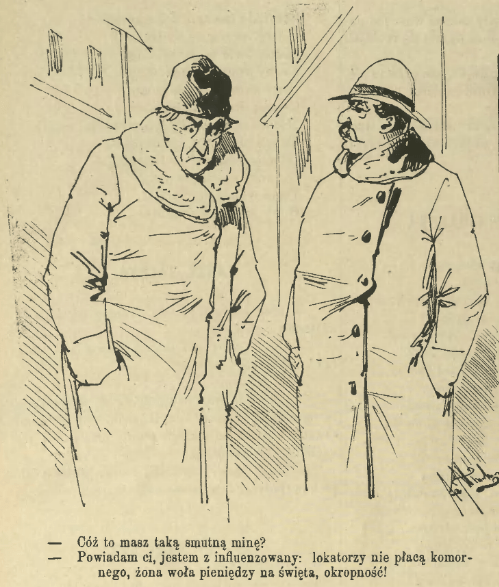

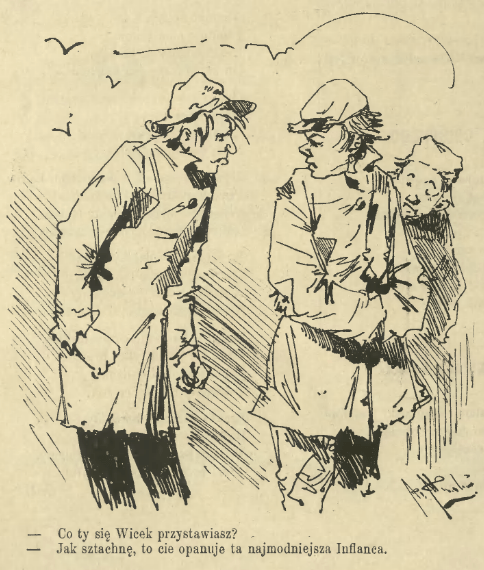

we suffer from the Russian snuff

and we in grace cheat ourselves.

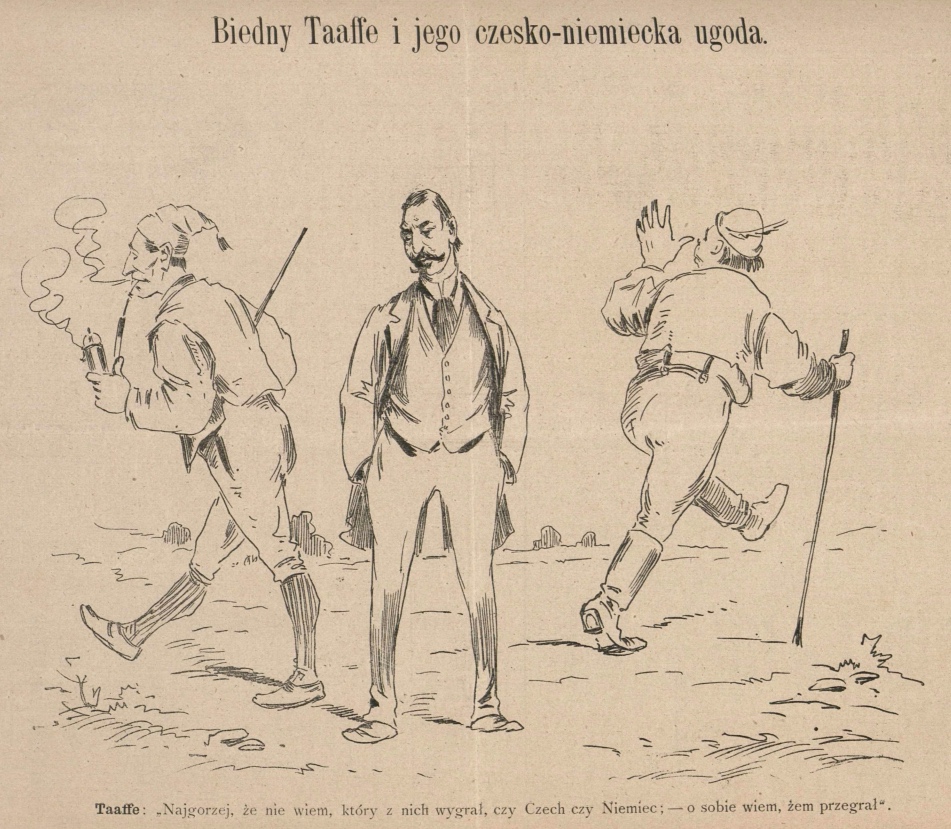

All of Europe’s sovereigns

have got a sense of the snuff;

but thrones shall not fall

just for this sudden catarrh…

Then England’s proud mistress

does not go free of the flu,

may Spain’s little king reconsider,

that she also rules over him.

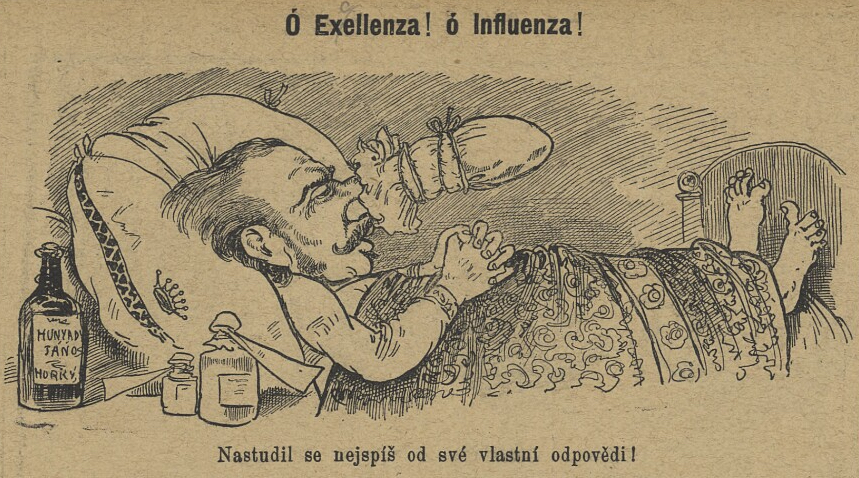

And look at Bismarck, look at him,

he was a grand old diplomat!

He cannot outsmart her,

she grabbed him neatly.

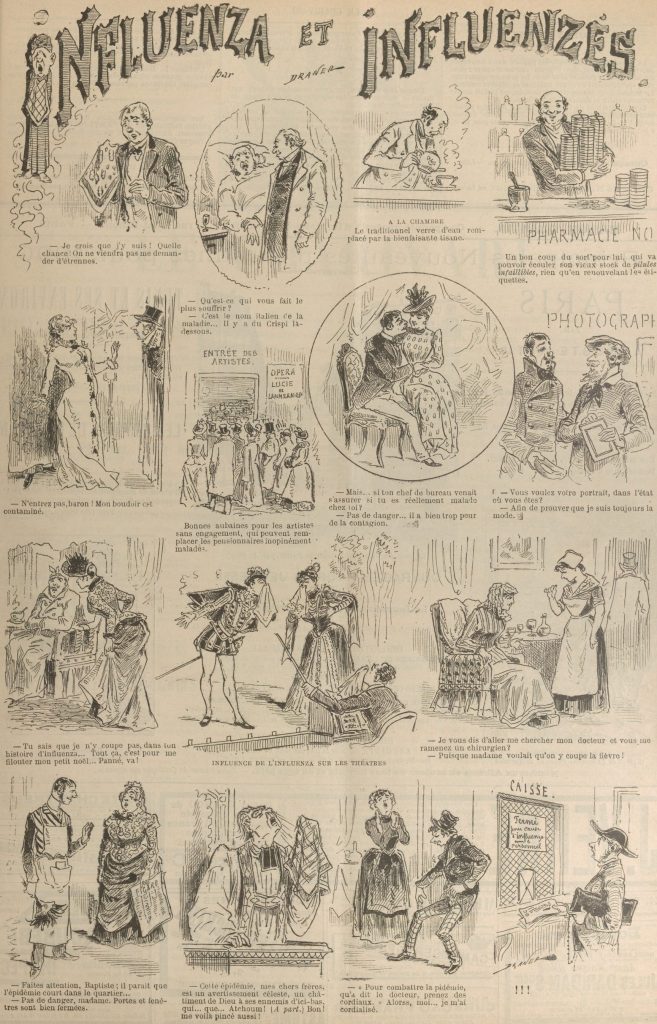

There, in the high courtrooms,

living doctors fall asleep easily;

but behold, she is still awake,

and you do not know her right.

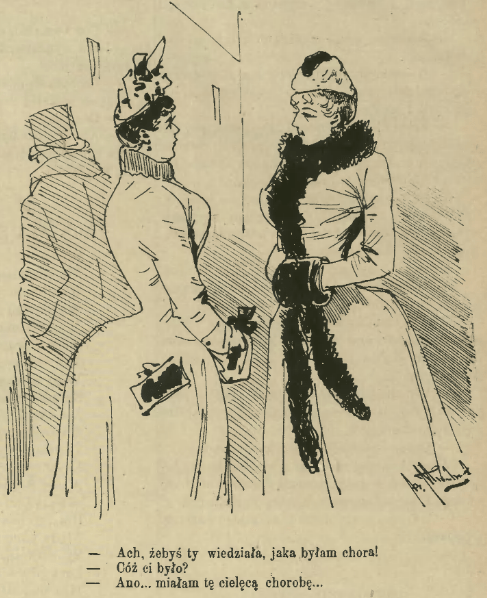

It has been said that she passes so gently:

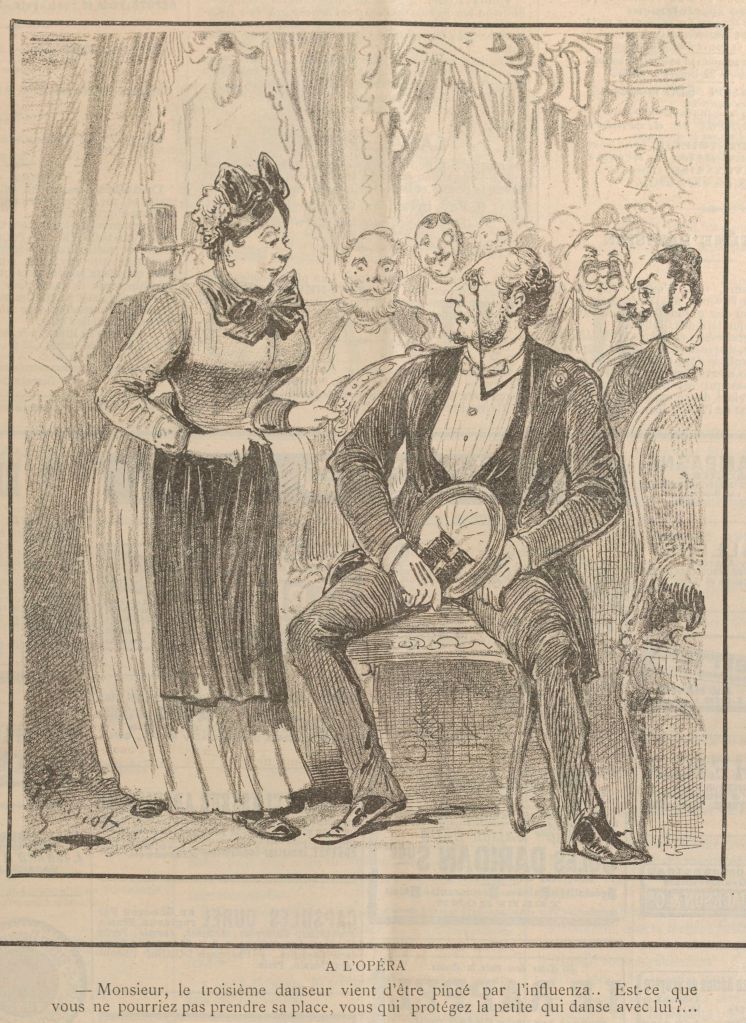

she pinches, but lightly and softly.

Well, it’s tiny! She cruelly martyrs royal purple.

Yes, the kingdom, it is sick.

(Fäderneslandet, Stockholm, 1889)