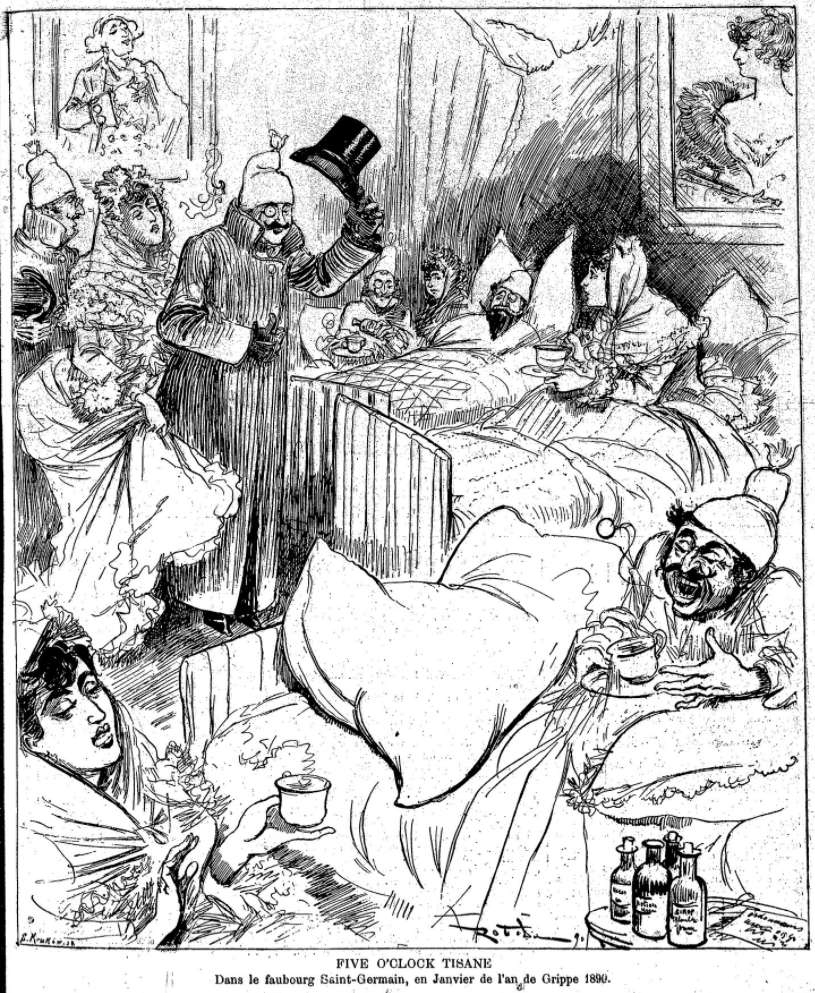

in the faubourg Saint-Germain, in January in the year of the Flu 1890

(La Caricature, Paris, 1890)

in the faubourg Saint-Germain, in January in the year of the Flu 1890

(La Caricature, Paris, 1890)

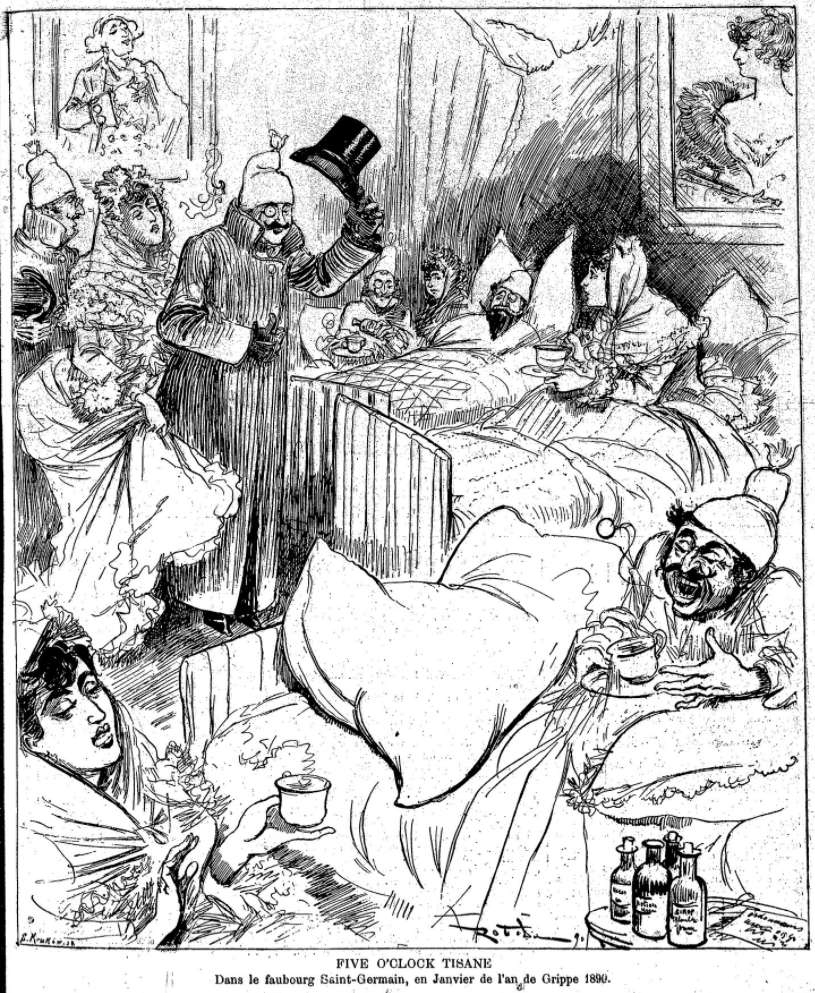

The orders they gave us are these: try to arrest the epidemic and lock it up in the clink.

(Charivari, Lisbon, 1890) (Shaky on the idiom; correction welcome.)

With the assistance of a bicycle during the influenza Doctor X managed the 112 visits that he had to make daily to his patients.

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1890)

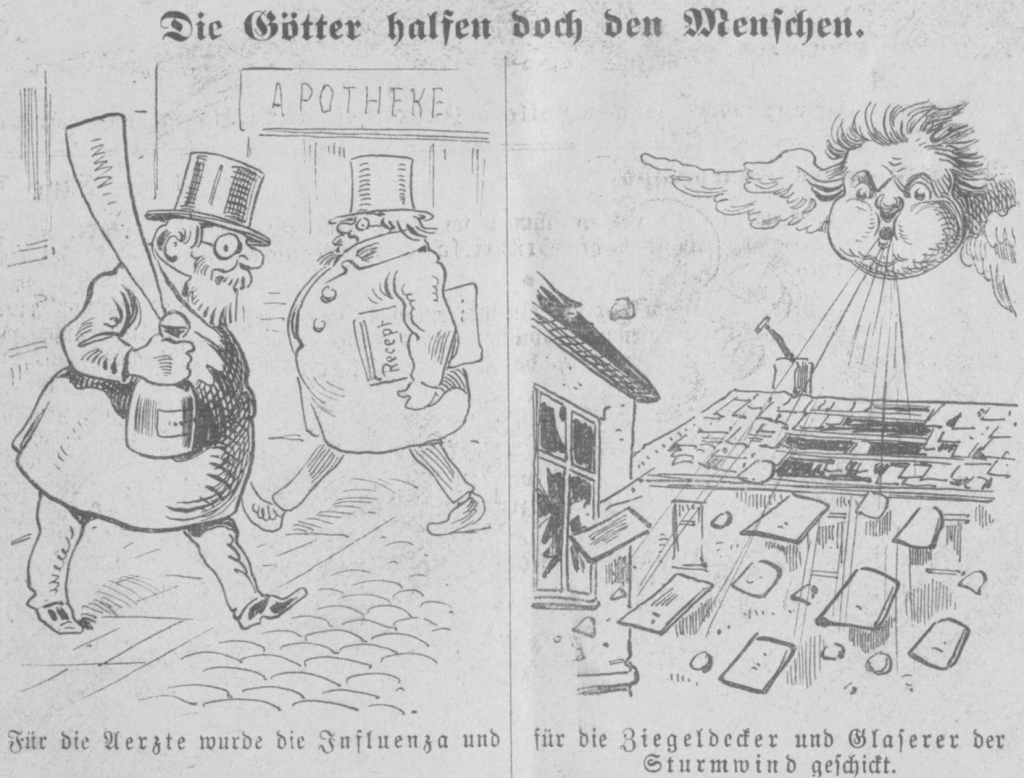

Influenza was sent for the doctors, and stormy winds were sent for the roofers and glazers.

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1890)

(After only schools and not government offices were closed for the sake of influenza.)

“O blessed, o blessed to be a child still!”

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1890)

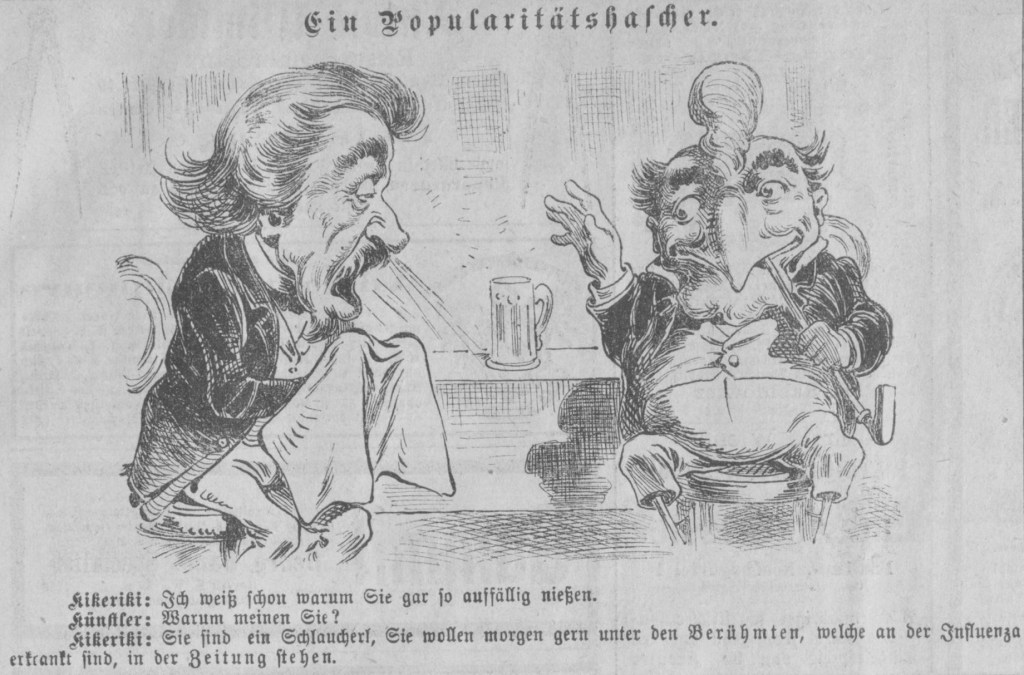

Kikeriki: “I know just why you’re sneezing so conspicuously.”

Artist: “What do you mean?”

Kikeriki: “You’re one of these clever types who would like to find themselves in the newspaper tomorrow among the famous people who are ill with influenza.”

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1890)

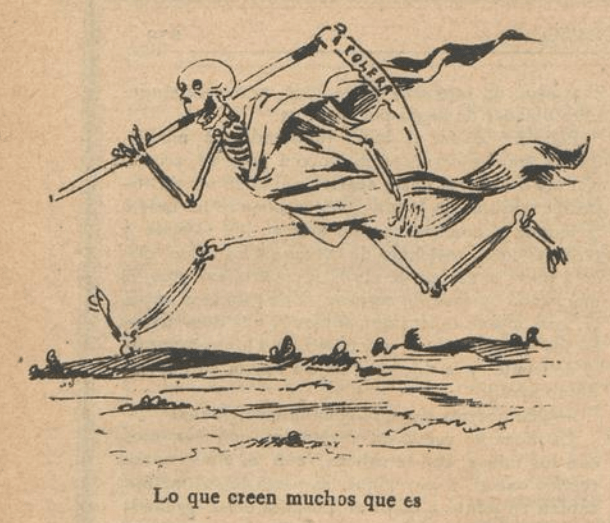

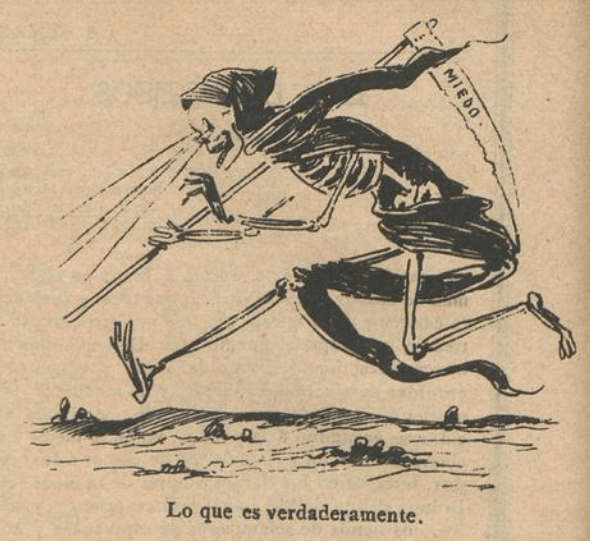

A multi-panel narrative by Mecachis (the pen name of Eduardo S. Hermua) in La Semana Cómico, Barcelona, 1890.

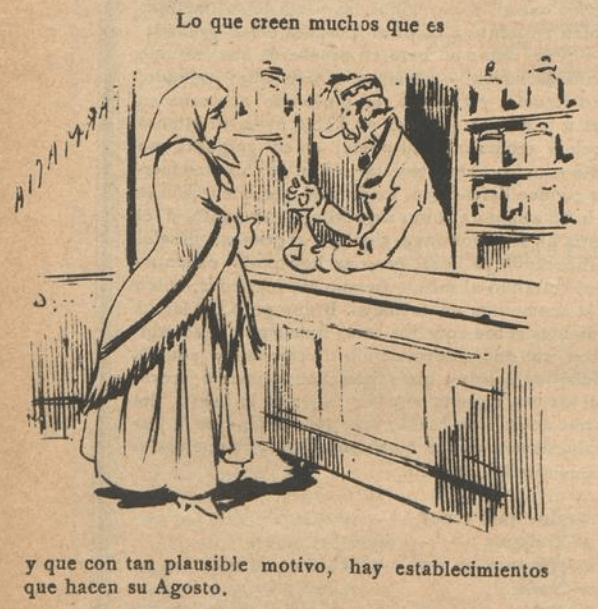

What many believe it to be

What it is in actuality.

Of course, between what is said and what is feared, there are people who find cases even in the soup;

so that, as a consequence, certain sites are extremely crowded

and that with such plausible motive, there are establishments that make their August [profit].

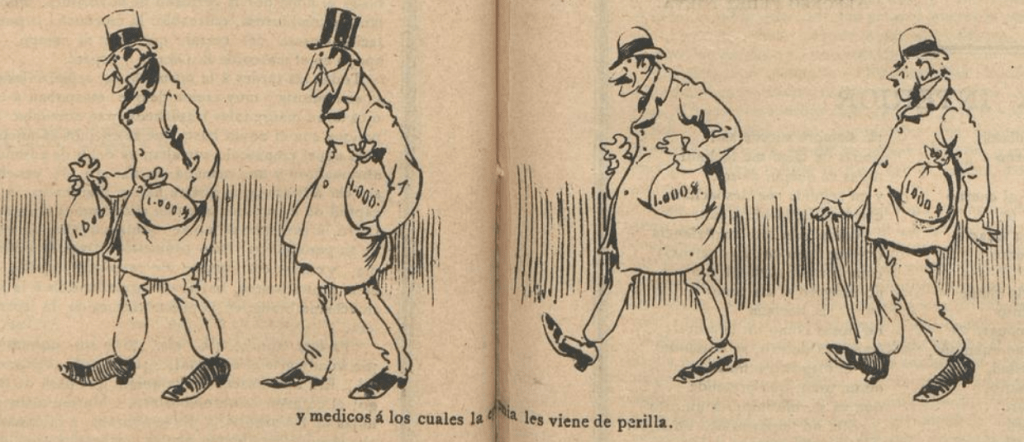

and doctors whom the epidemic thoroughly suits.

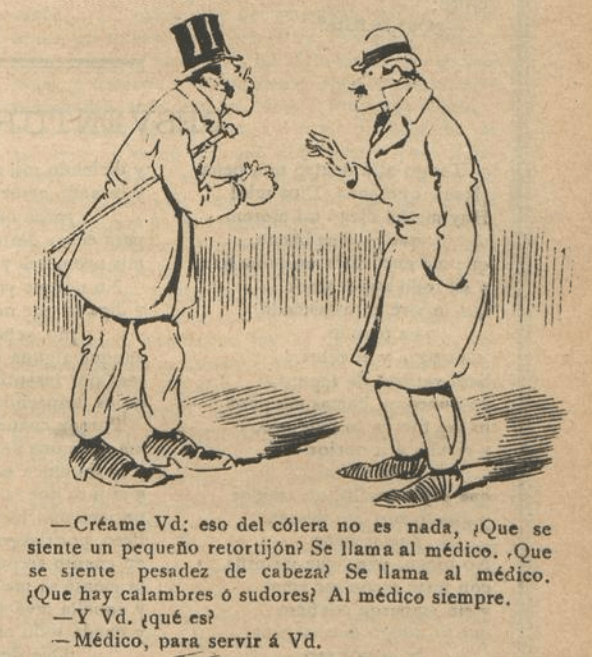

“Believe me: this cholera is nothing. Do you feel a little wooziness? Call the doctor. Headache? Call the doctor. Cramps or sweats? Always to the doctor.”

“And what are you?”

“A doctor, to serve you.”

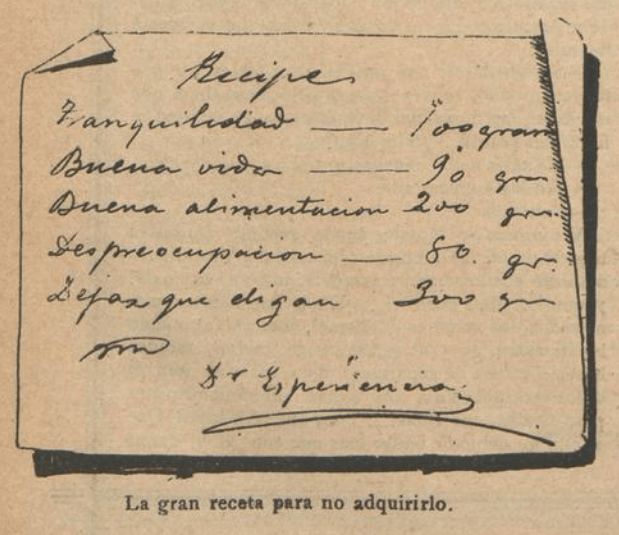

The big prescription you can’t get [rest, the good life, good nutrition, etc.].

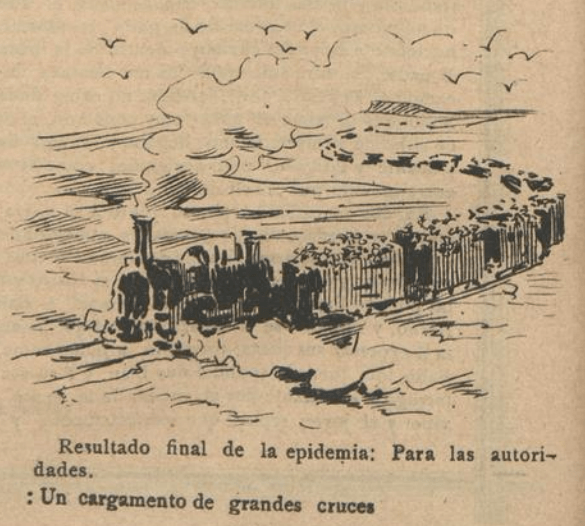

Final result of the epidemic: For the authorities: A shipment of large crosses

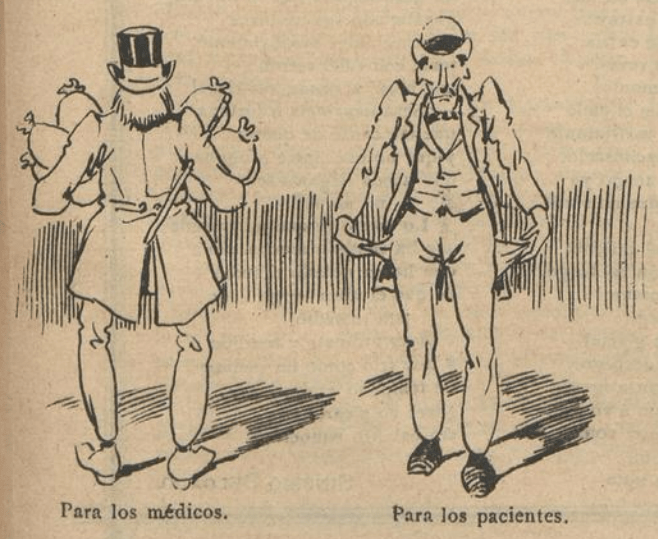

For the doctors. For the patients.

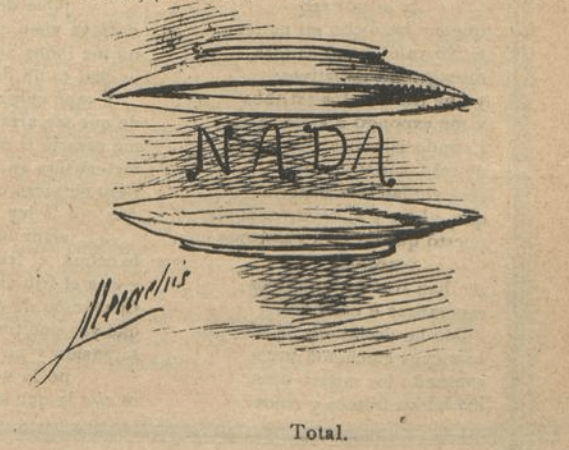

In sum: Nothing left

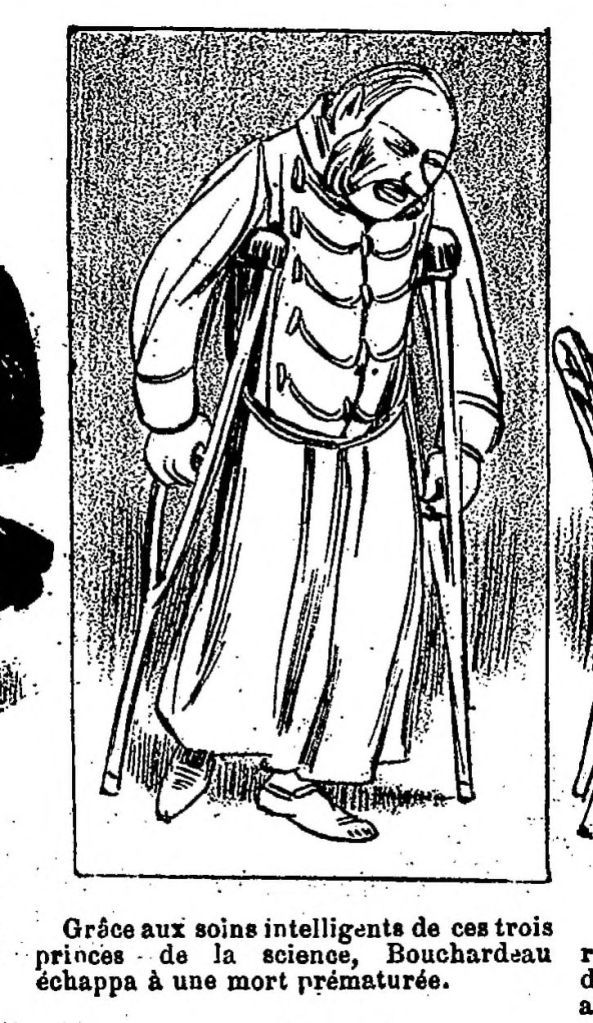

From La Caricature (1890):

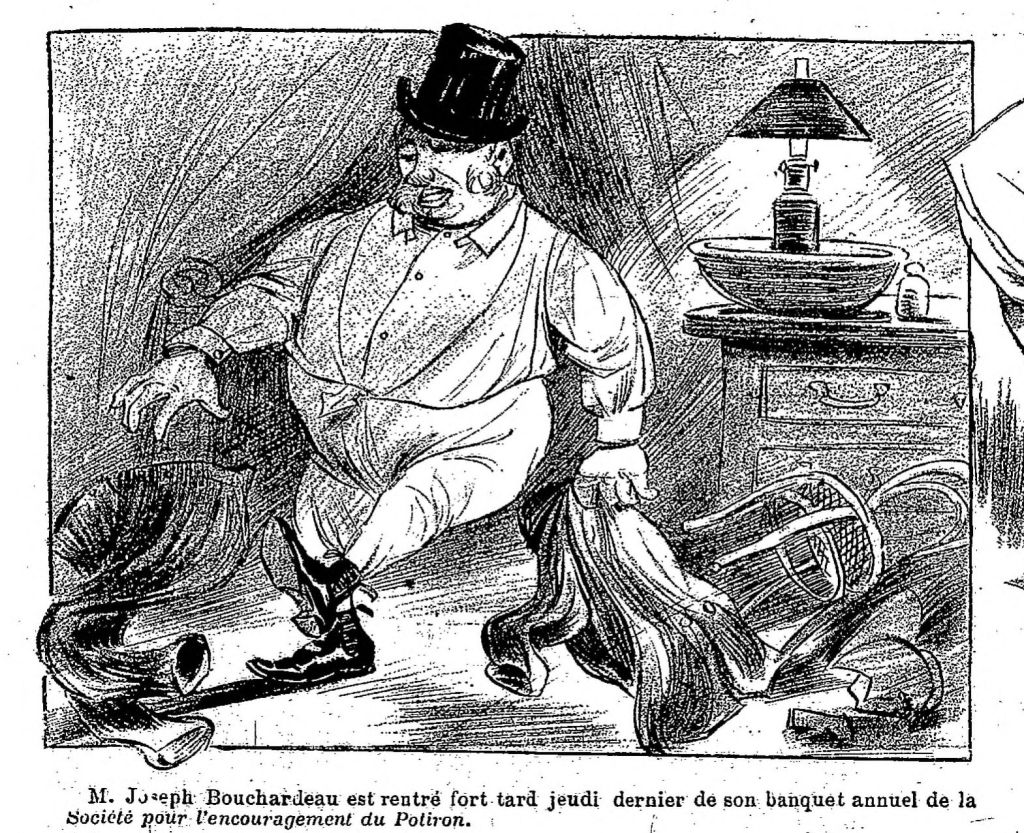

Mr. Joseph Bouchardeau returned very late last Thursday from his annual banquet at the Society for the Encouragement of the Pumpkin.

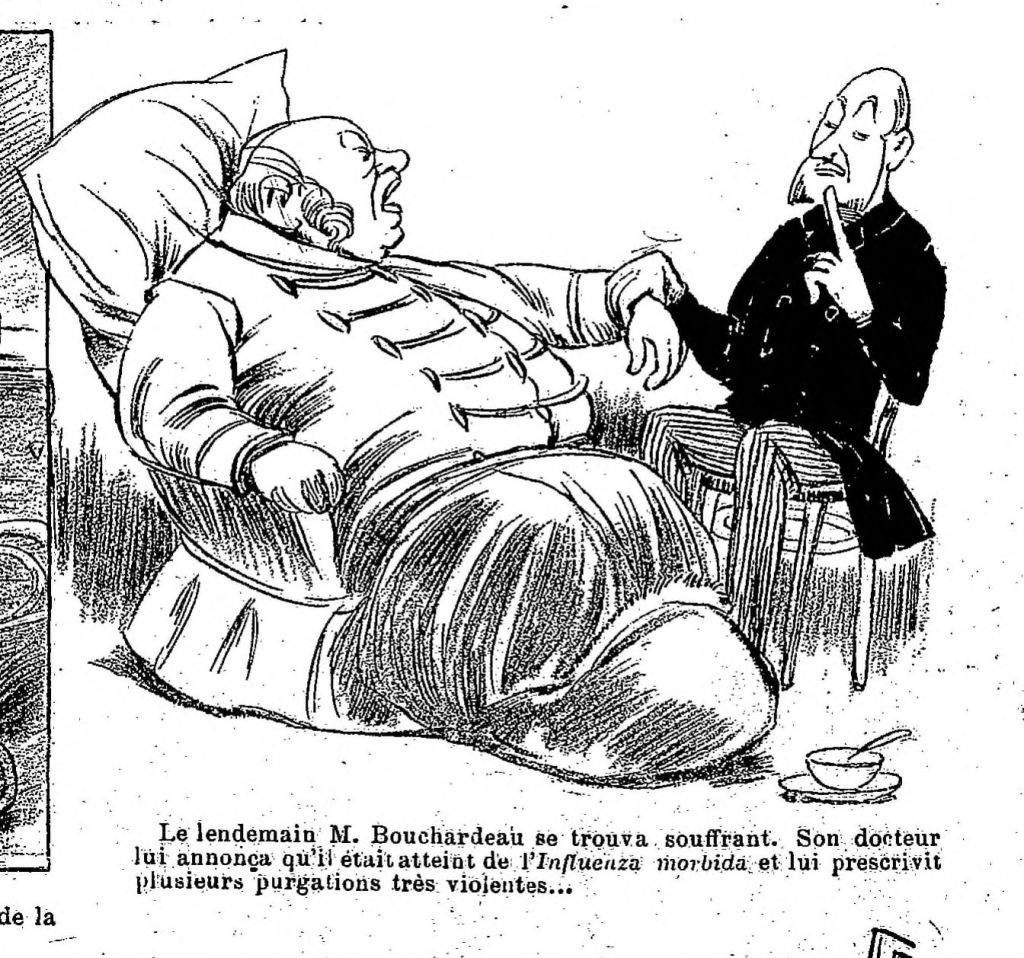

The next day Mr. Bouchardeau found himself ill. His doctor told him that he had morbid influenza and prescribed several very violent purgations…

These gave him the opportunity to get plenty of exercise, but the influenza persisted.

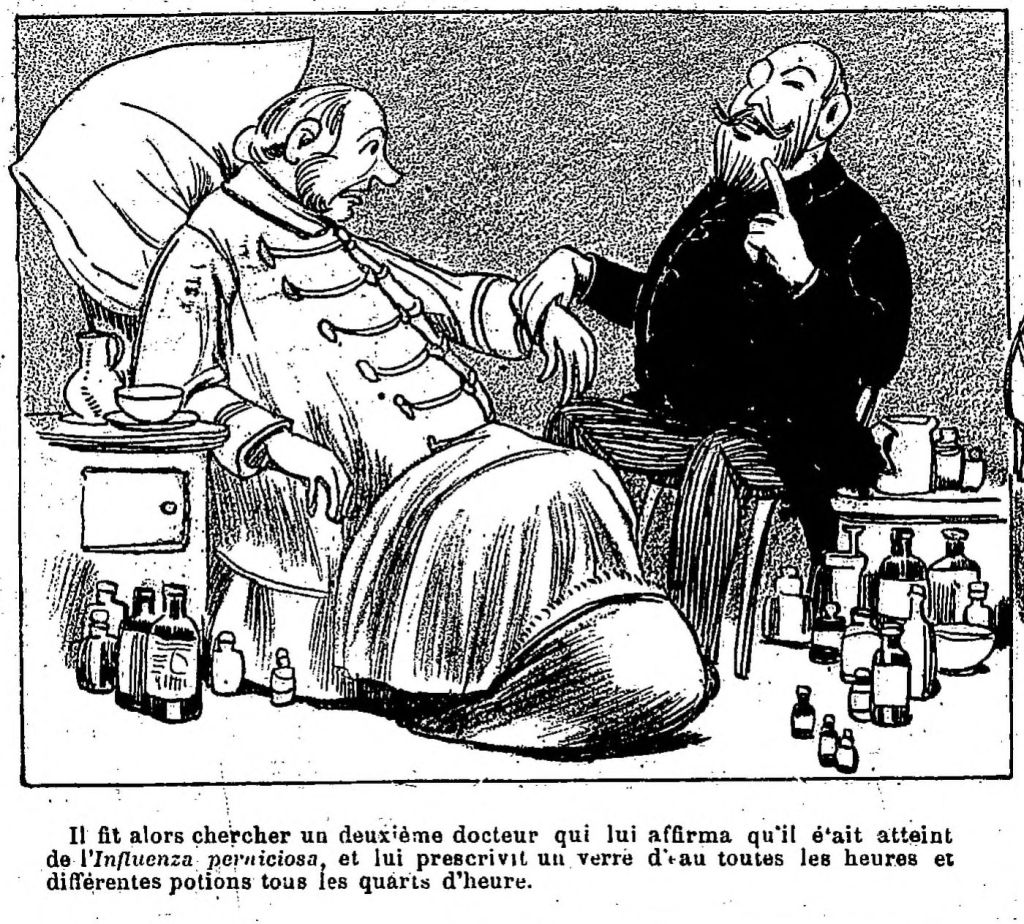

He then sent for a second doctor who told him that he had pernicious influenza and prescribed him a glass of water every hour and different potions every quarter of an hour.

Mr. Bouchardeau noted with sadness that he was visibly declining and that the pernicious influenza persisted anyway.

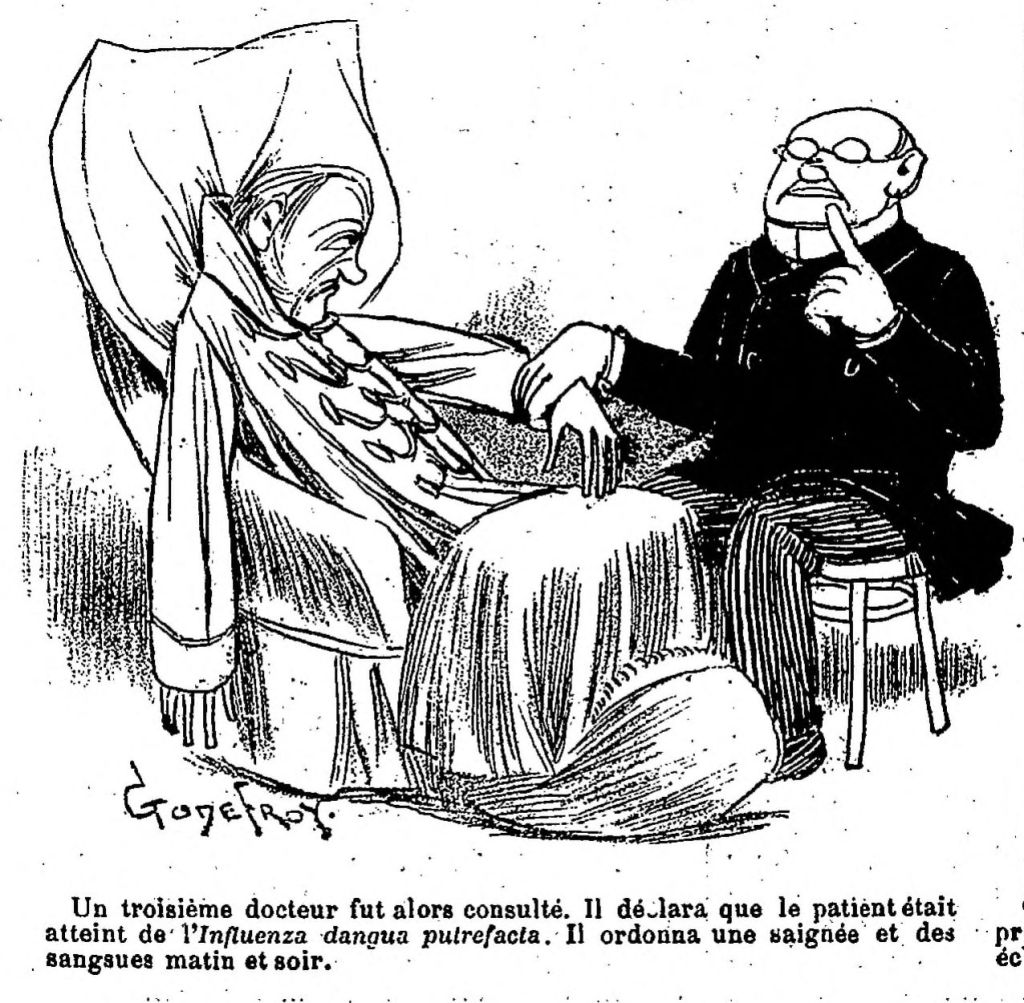

A third doctor was then consulted. He declared that the patient had influenza dangua putrefacta. He ordered bleeding and leeches morning and evening.

Thanks to the intelligent care of these three princes of science, Bouchardeau escaped a premature death.

So it was with a feeling of deep gratitude that he paid the bills of doctors, pharmacists, herbalists, etc., who had contributed to his salvation. However, he reflected that the annual pumpkin dinner was costing him a bit dearly, and he resolved to abstain from it henceforth.

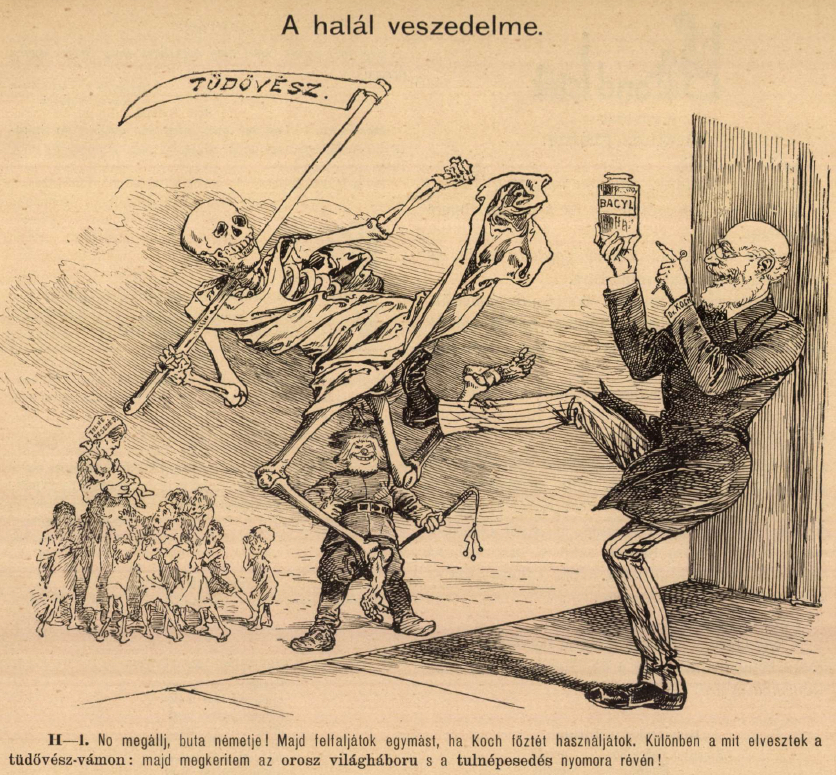

Death: “Well, stop it, silly German! You’re about to devour each other if you use Robert Koch’s concoction. Anyway, whatever I lost in my tuberculosis tariff, I will get hold of through the misery of the Russian world war and overpopulation!” (A reference to the Russian repudiation of alliances with Germany and Austro-Hungary in favor of France, its failed politics in the Balkans, and renewed tensions with imperial Britain in Central Asia.)

(Bolond Istók, Budapest, 1890)

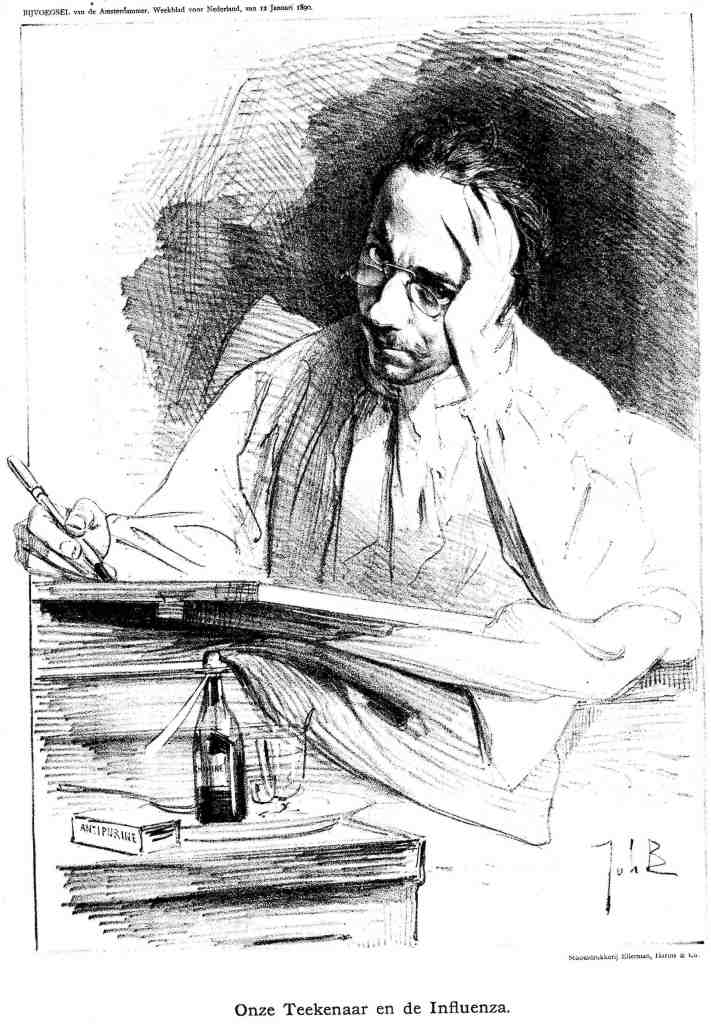

This spare image is fascinating, appearing when an influenza epidemic had prevailed for more than two months in the city of Amsterdam, at a dramatic cost of nearly one in thirty residents every week. The artist, his own medicaments at hand, seems to be contemplating, not so much his own clinical predicament, but how to represent the crisis in visual terms. The self-portrait might represent his interim solution to a dilemma he is not sure how to address satirically. (The irregular Bijvoegsel supplement was most often humorous in content.)

(De Amsterdammer, Amsterdam, 1890)

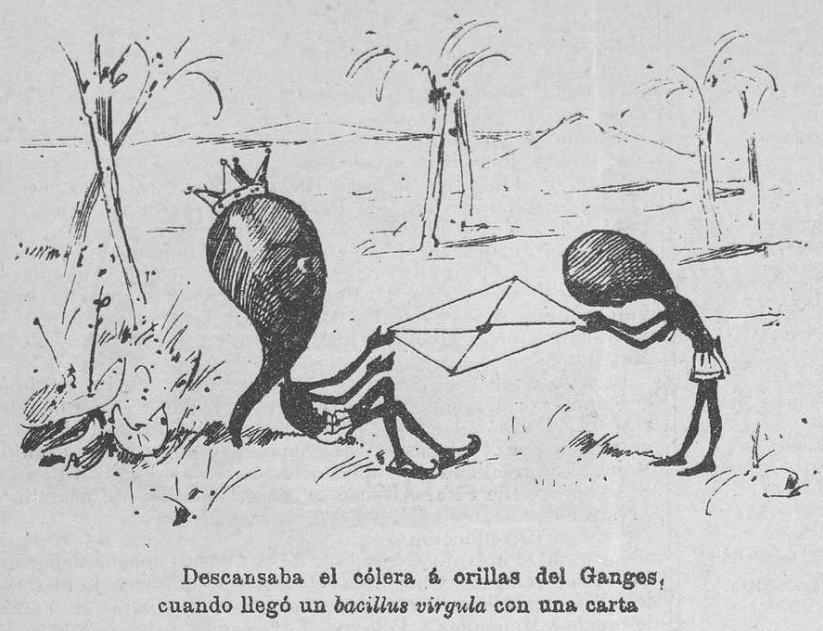

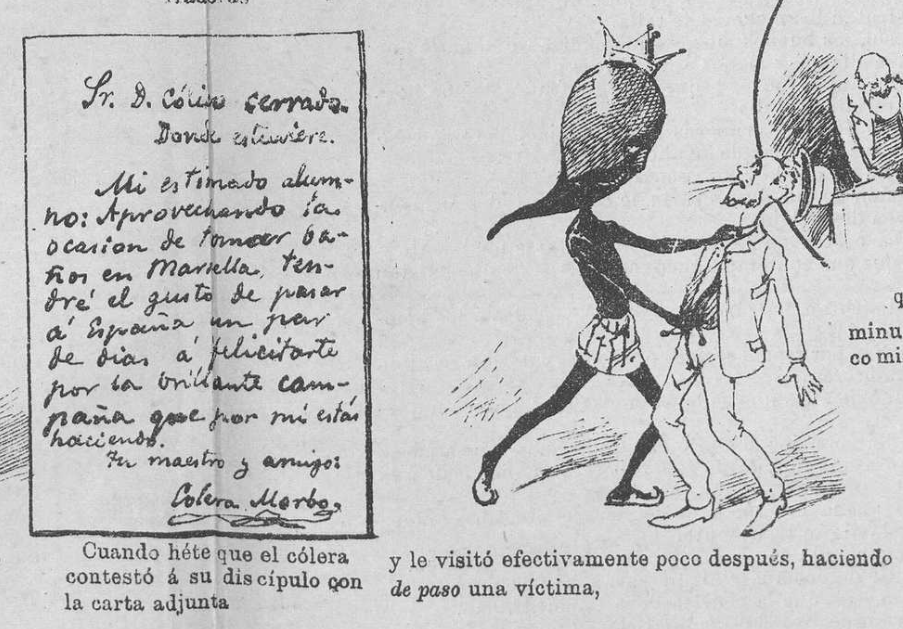

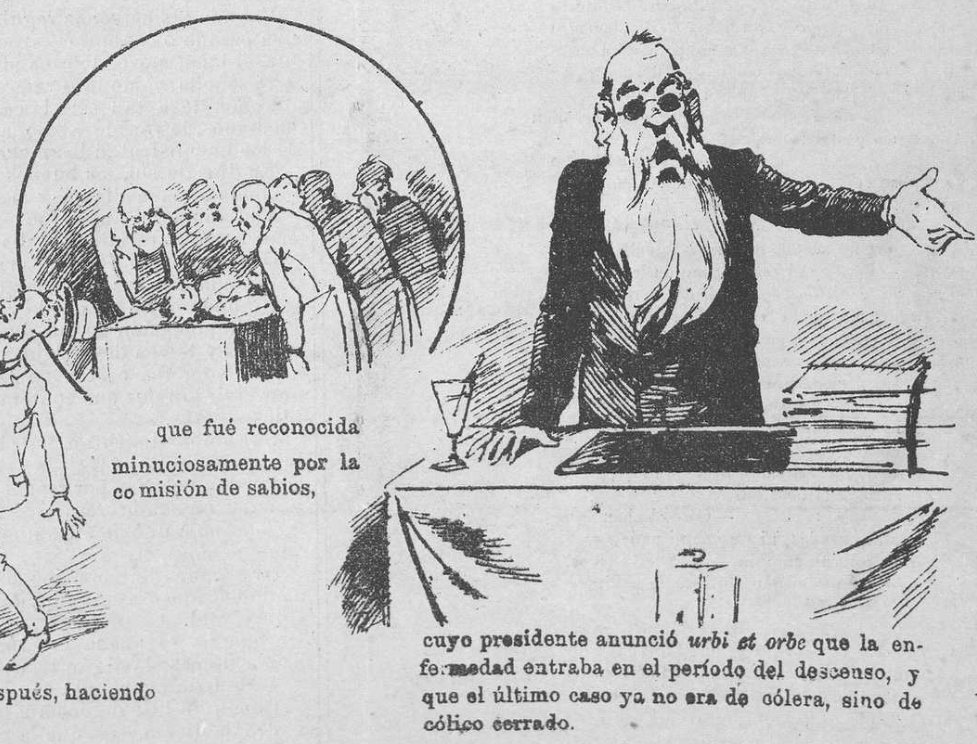

A multi-panel narrative from Madrid cómico (1890):

The cholera was resting on the banks of the Ganges when a virgula bacillus arrived with a letter that said the following:

The governor, who was not secreted away, dictated severe provisions

and appointed a numerous and distinguished commission of wise men,

which, before setting off, wrote an enlightening report on the necessary precautions in such cases.

Already within the commission’s domain, the consequences of the disease were attentively and carefully observed, and it was declared that there is no doubt that it was the true morbid cholera of the worst kind.

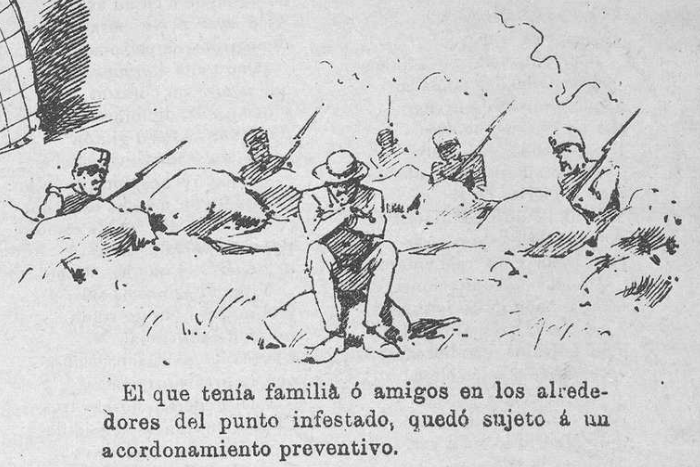

Anyone who had family or friends around the infected site was subject to a preventive cordon.

The official news was increasingly terrifying

And people were entertained with always healthy fumigations and fires.

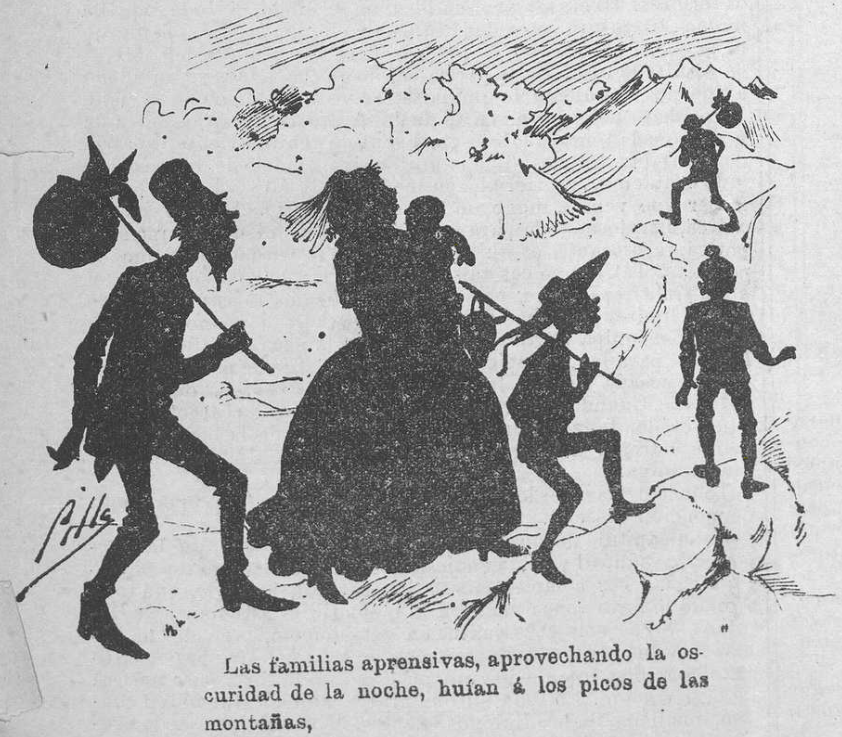

Apprehensive families, taking advantage of the darkness of the night, fled to the mountain peaks,

and clinics for travelers were established everywhere.

When the cholera answered his disciple with the attached letter and visited him shortly afterwards, making him a victim in passing,

it was meticulously recognized by the commission of wise men, whose president announced urbi et orbi that the disease was entering the period of decline, and that the last case was no longer cholera, but colic.

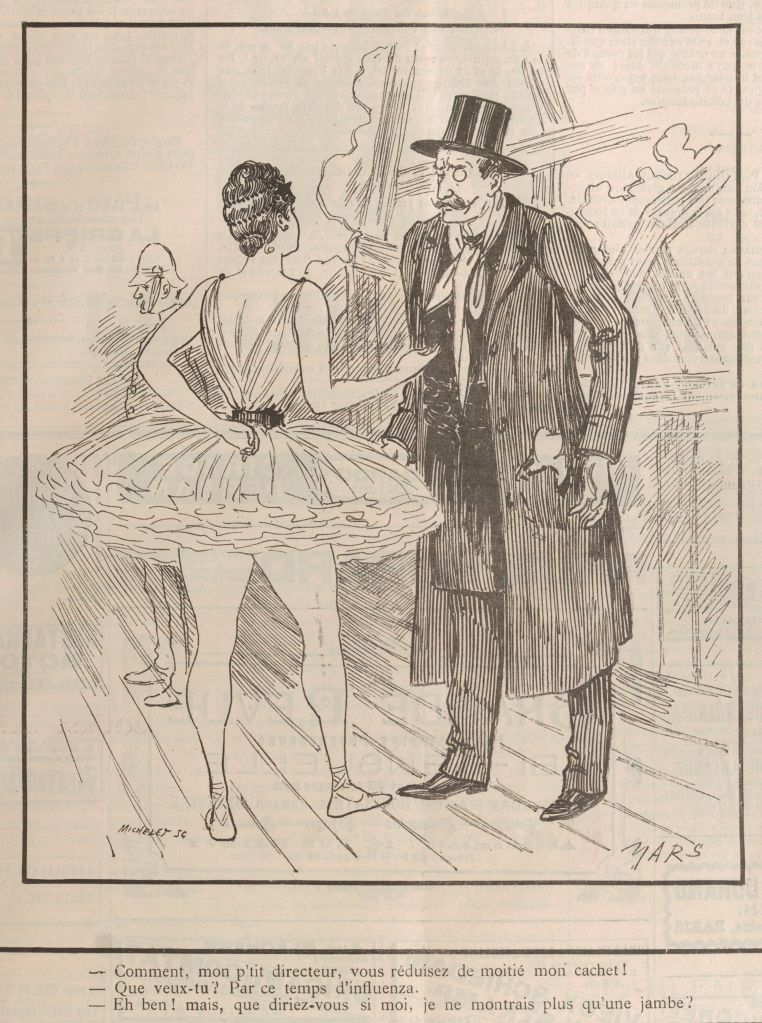

“My dear little director, how is it that you have cut my fee in half!”

“What do you want? It’s this time of influenza.”

“Well! But what would you say if I only showed one leg?”

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1890)

“You complain of headache, madame, and you also have some fever. It seems to be a mild case of influenza, a sort of influenza-straggler…”

“You will prove wrong, finest doctor, examine better. I take care to join in a fashion only when it is completely new.”

(Die Bombe, Vienna, 1890)

The quaestor replacing the legendary glass of water with assorted herbal teas.

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1890)

From Humoristické listy, Prague, 1890.

“Hey you, ‘borrow’ a magazine somewhere.”

“You wanna entertain yourself with politics?”

“Hah! I would just like to know if they also shut down criminals now like they do schools. Then there would be something more to do.”

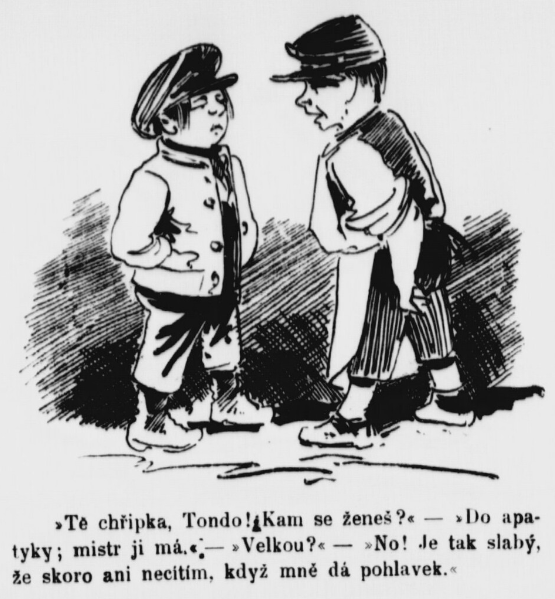

“You’ve got the flu, Tony! Where are you going?”

“To the pharmacy; the master has it, too.”

“Is that so great?”

“No! He’s so weak that I can’t even feel him slapping me.”

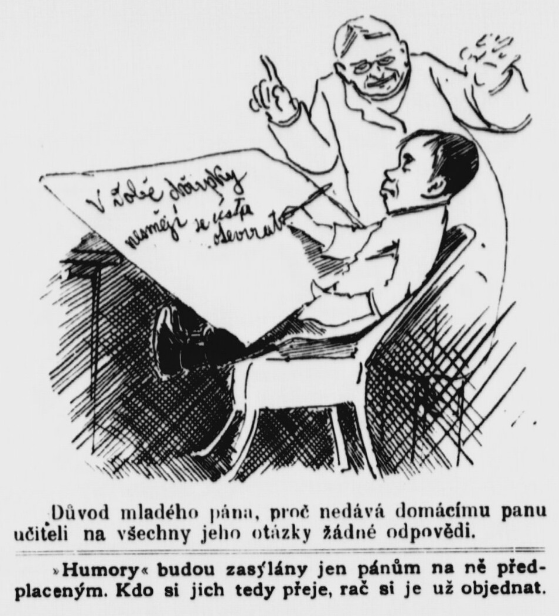

(Child writing on school desktop: “During the flu mouths must not be opened”)

The young man’s reason for not giving the teacher any answers to all his questions.