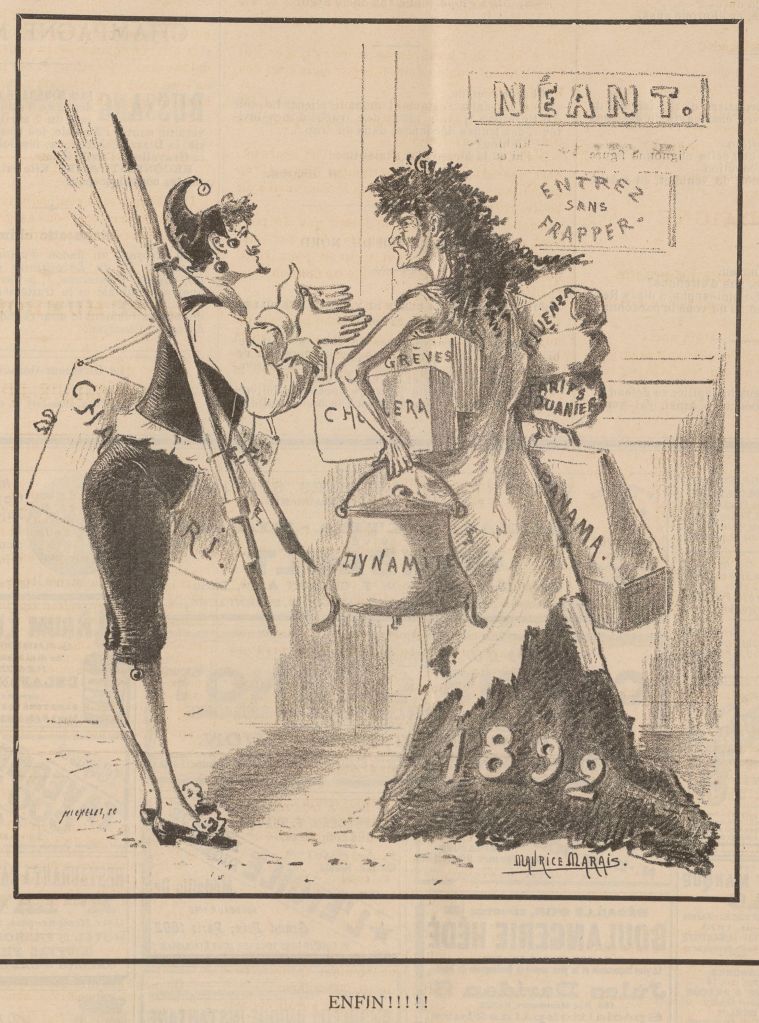

The year 1892 finally exits the store carrying her acquisitions: dynamite, cholera, strikes, influenza, tariffs, and the Panama Canal scandal.

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1892)

The year 1892 finally exits the store carrying her acquisitions: dynamite, cholera, strikes, influenza, tariffs, and the Panama Canal scandal.

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1892)

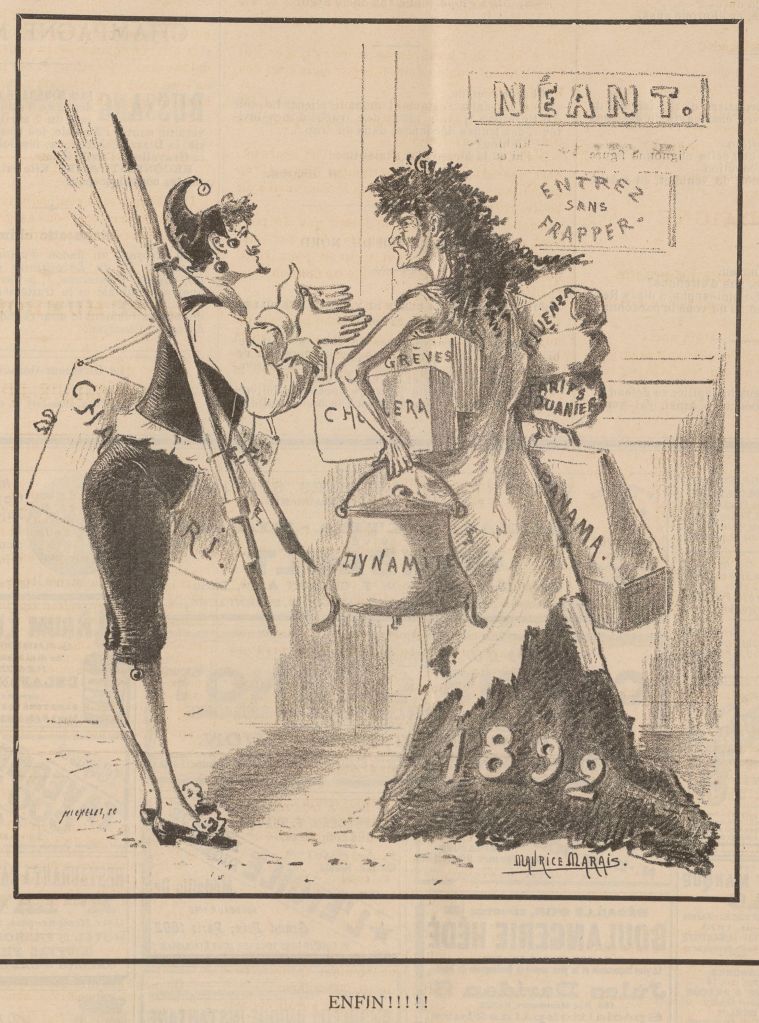

The police force their way despite resistance from residents into a building suspected of cholera, in order to undertake disinfection of the flats. According to the accompanying story, the building was in one of the most densely populated sections of Budapest, with more than 600 residents. In the entryway thirty-two policemen were met with a shower of vegetables, pickles, refuse, manure, and stones. Once inside, some were scalded with cooking water by infuriated women. The editors faulted the city fathers for not instructing the populace about the nature of cholera and the precautionary measures in a timely fashion.

(Das interessante Blatt, Vienna, 1892)

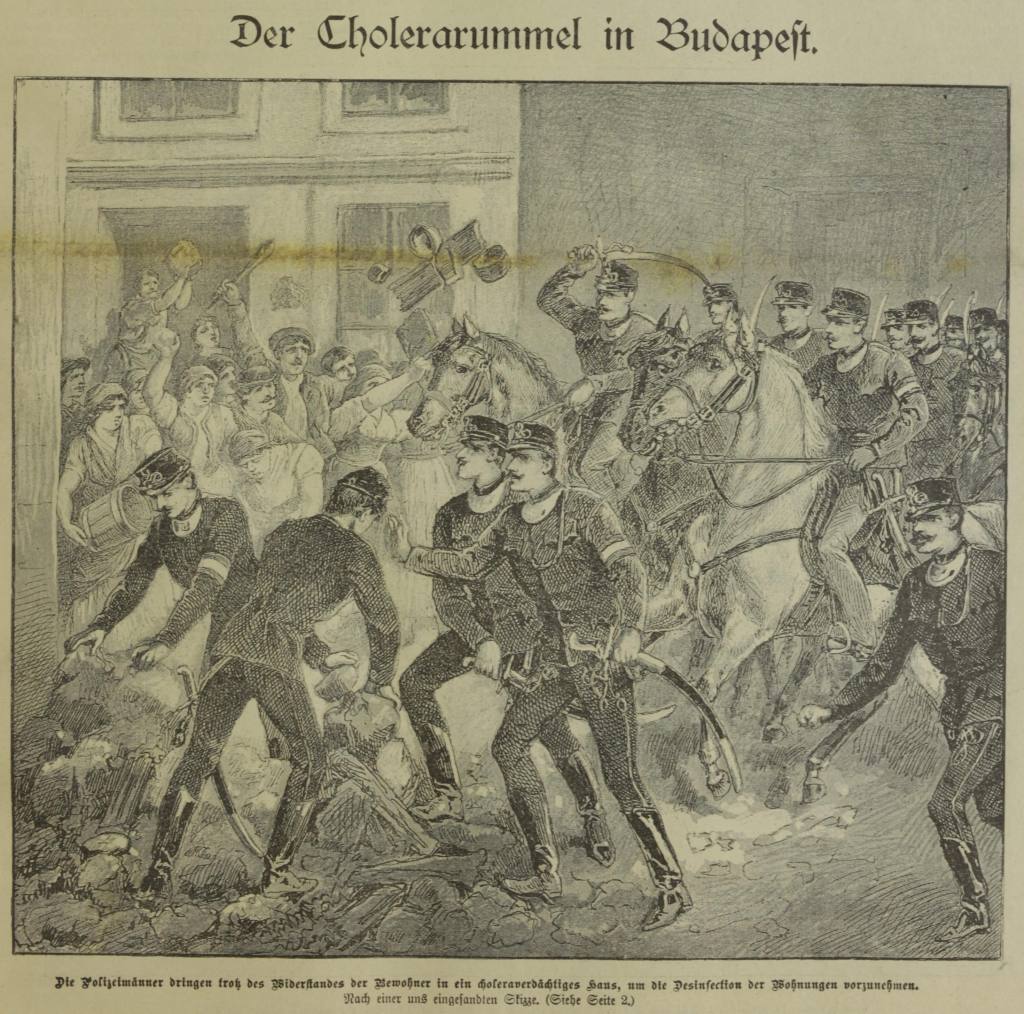

The police in Sommermoll tolerate no unripe fruit at the market; these are immediately thrown away, so that they can do no harm.

Nebelspalter, Zurich, 1892.

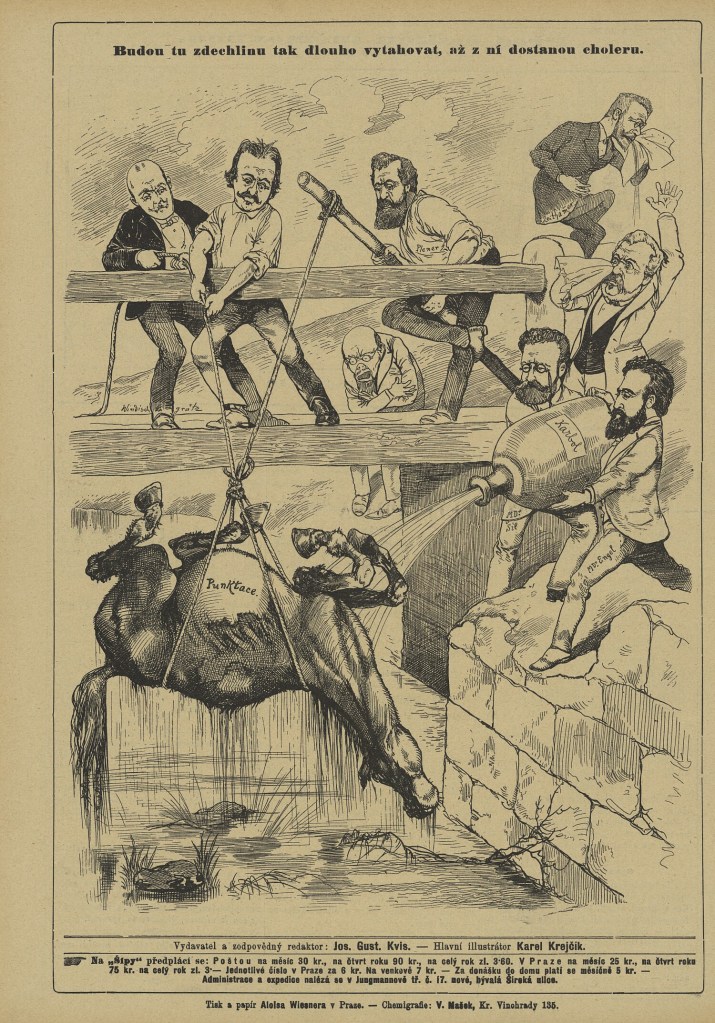

This is an elaborate and slightly intriguing variant on the disease metaphor in politics. Since before the Austro-Hungarian Ausgleich of 1867, Czech nationalists had aspired to a similar agreement with the German-speaking populace in the Bohemian lands. The Old Czech faction pressed repeatedly for a formal list of potential points of agreement (the dead horse labeled “Punktace”), largely centered on a strategy of cooperation with the great landowners and loyalty to the Habsburg monarchy. After 1874 the Young Czech faction rejected this strategy and demanded more direct representation in the parliament, hobbling any compromise. The Old Czechs made a final push for an agreement in 1890, but with the victory of the Young Czechs in the elections the following spring, any prospect for its success faded from view. This cartoon from the Prague satirical journal Šípy in 1892 mocks several Old Czech politicians as they endeavor to lift the dead horse, one applying generous quantities of carbolic acid.

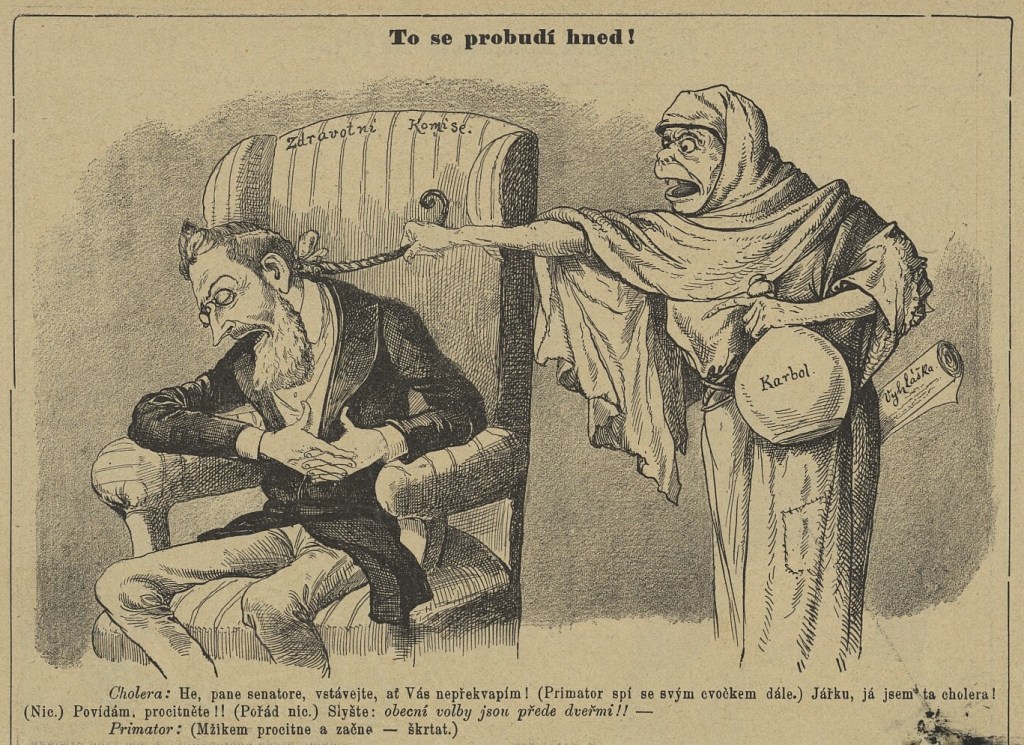

Health Commission (armchair). Cholera, bearing a container of carbolic acid and a decree in her pocket, pulls the pigtail of the mayor of Prague: “Hey, Senator, get up, I wouldn’t want to catch you by surprise!” (The mayor sleeps further with his spectacles.) “I say, I’m the cholera!” (Nothing.) “I’m telling you, wake up!! (Still nothing.) “Listen: the municipal elections are at the front door!!“

Mayor of Prague: (Instantly wakes up and starts making budget cuts.)

(Czech satirical magazine Šípy, Prague, 1892)

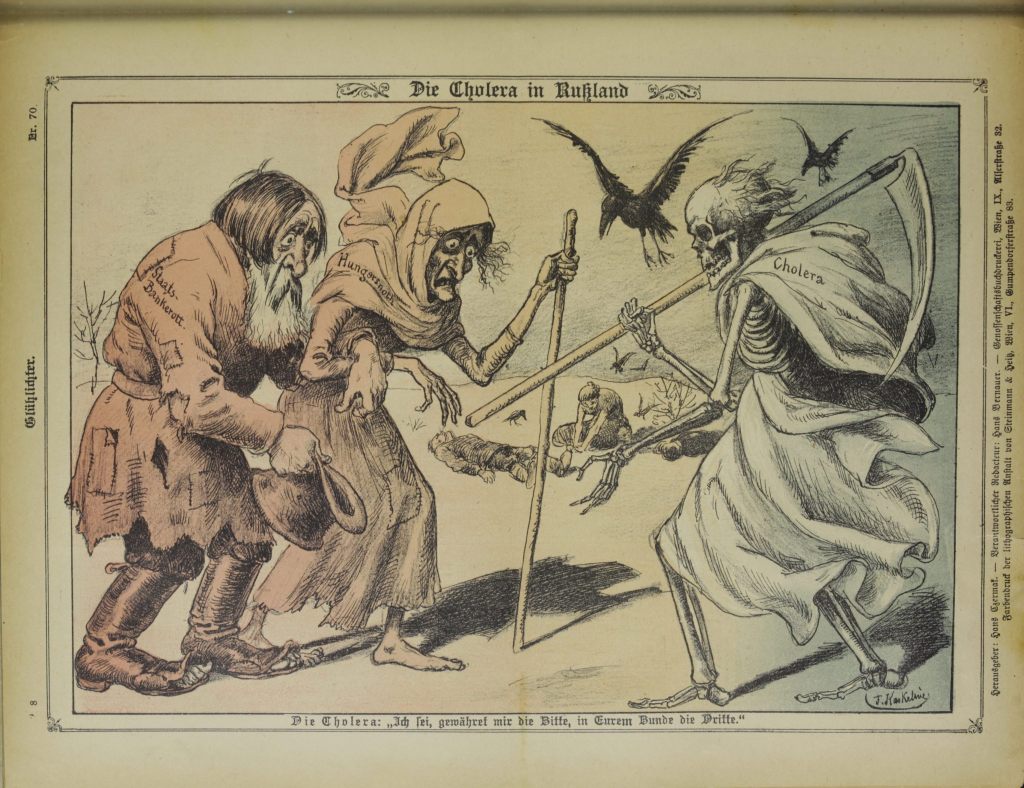

To state bankruptcy and famine: “Were you to grant my request, I would be the third member of your alliance.”

(Glühlichter, Vienna, 1892)

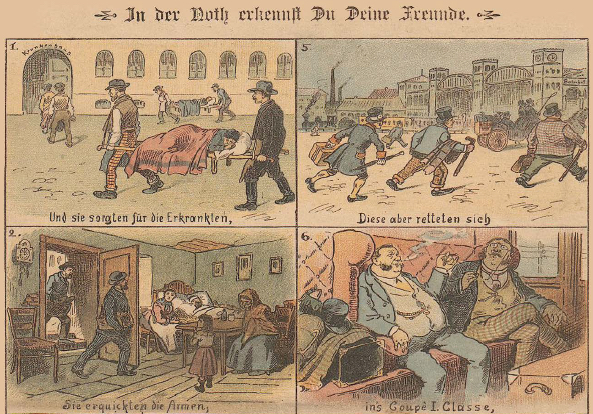

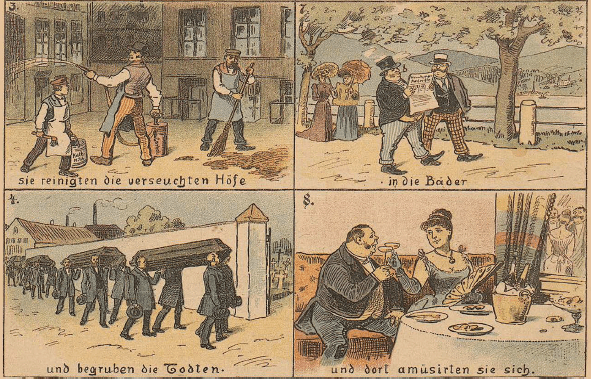

From Der wahre Jacob no. 162, Stuttgart, 1892:

1. And they cared for the sick,

2. they comforted the afflicted,

3. they cleaned the infected courtyards

4. and buried the dead.

5. Yet these saved themselves

6. in first class,

7. in the spas

8. and enjoyed themselves there.

Jeremiah Fastidious and his patented anti-cholera equipment.

(Figaro, Vienna, 1892) (There is a similar image from the 1918 flu pandemic. The satirical theme goes back at least to 1832, in this marvelous example preserved by the Wellcome Collection.)

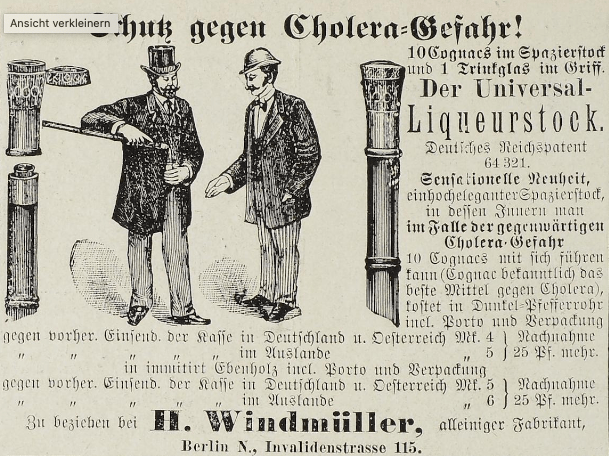

If you are anxious about venturing out in these pandemic times, may I suggest Mr. Windmüller’s “highly elegant” Liquor Cane (German patent 64321), which holds ten shots of cognac to protect you against disease. (Meggendorfers Humoristische Blätter, 1892)

Cholera draws the curtain on a slum and speaks to the public health commission: “Grasp the life of man complete, and wherever you touch, there’s interest without end!” (Glühlichter, Vienna, 1892) A colleague points out that this phrasing is taken from a text known to any contemporary German speaker: the Prelude to Goethe’s Faust.

In other words, there is ample precedent to talk about differential privilege in physical distancing.