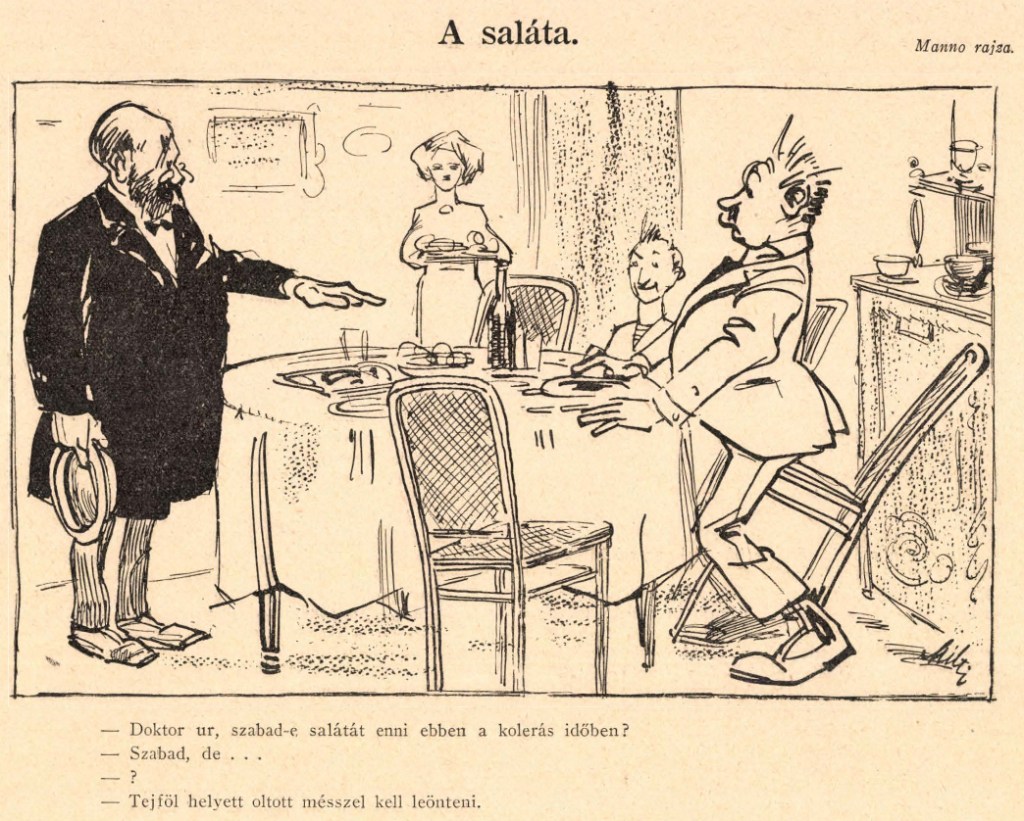

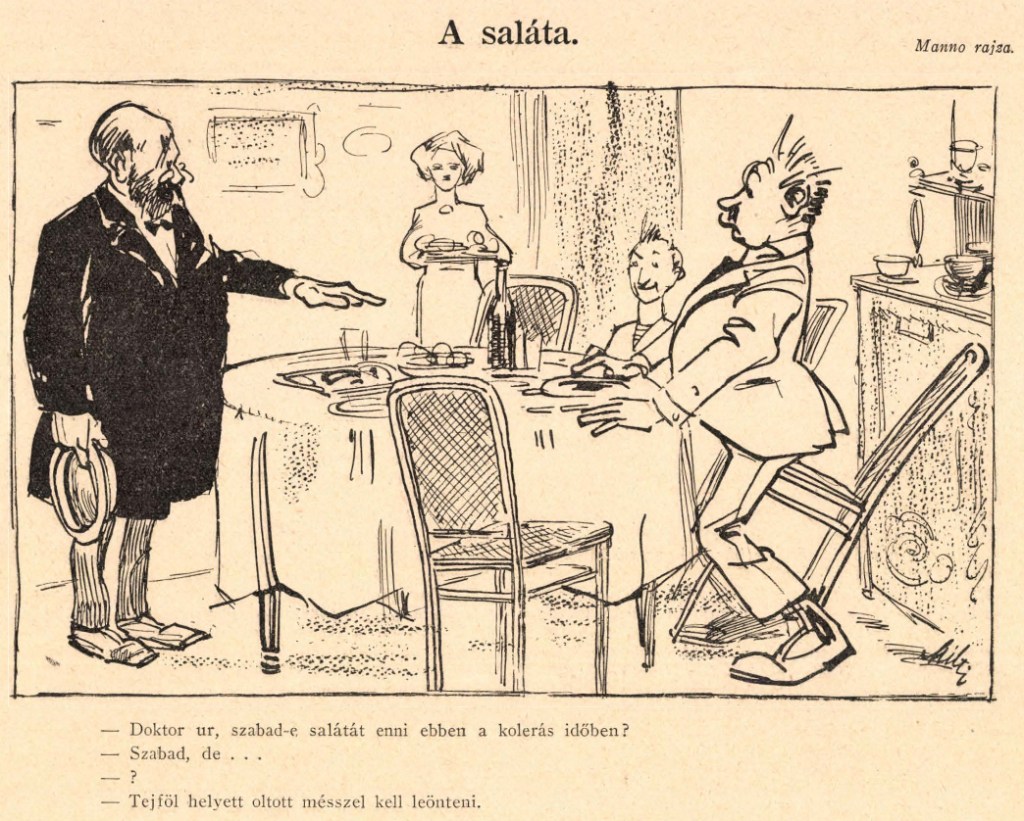

“Doctor, is it OK to eat salad in a time of cholera?”

“Yes, but…”

“What?”

“Instead of pouring sour cream on it, you should use slaked lime.”

(Kakas Márton, Budapest, 1910) (Arcanum)

“Doctor, is it OK to eat salad in a time of cholera?”

“Yes, but…”

“What?”

“Instead of pouring sour cream on it, you should use slaked lime.”

(Kakas Márton, Budapest, 1910) (Arcanum)

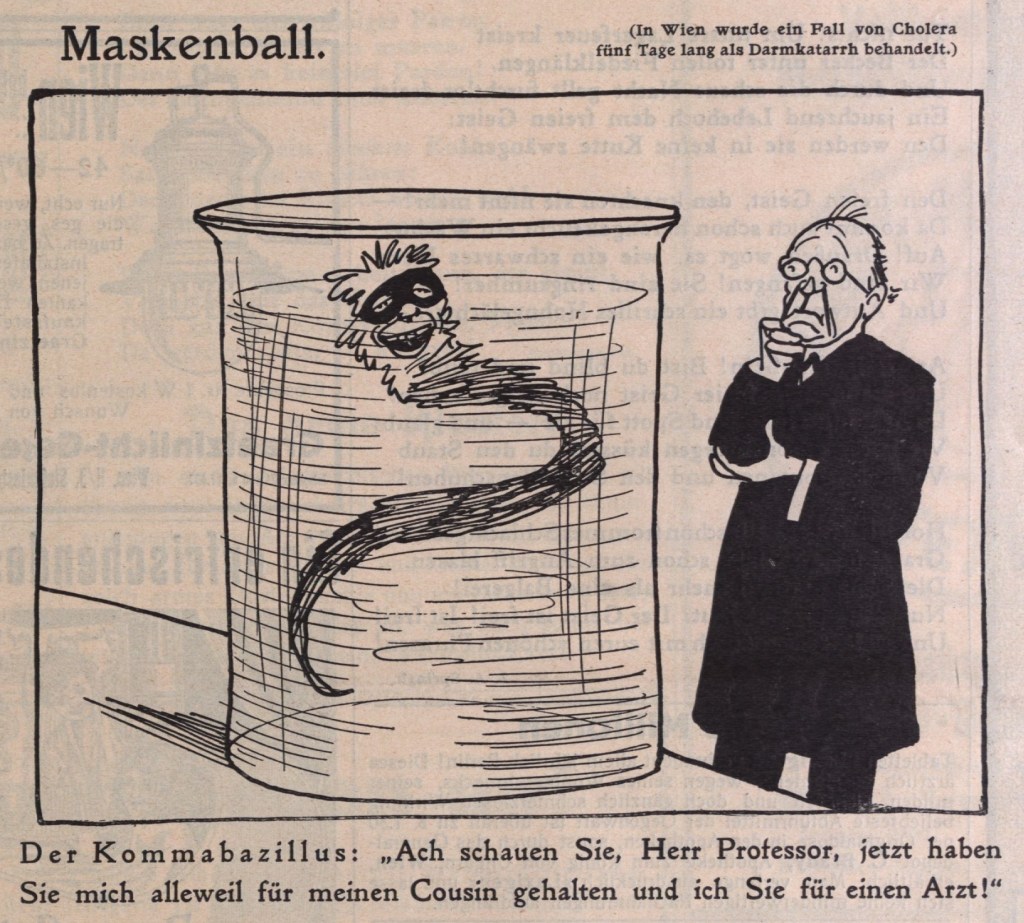

(In Vienna a case of cholera was treated for five days as intestinal catarrh.)

Comma Bacillus [found in the intestines of patients suffering from cholera]: “Look here, Herr Professor, now you have taken me the whole time for my cousin and I’ve taken you for a doctor!”

(Die Muskete, Vienna, 1910)

“The Russian regime has initiated an aid campaign against famine, since a radical solution of the problem has been made possible by cholera anyhow.” (Meaning it’s just for show and the weak state won’t have to try very hard.)

(Die Glühlichter, Vienna, 1910)

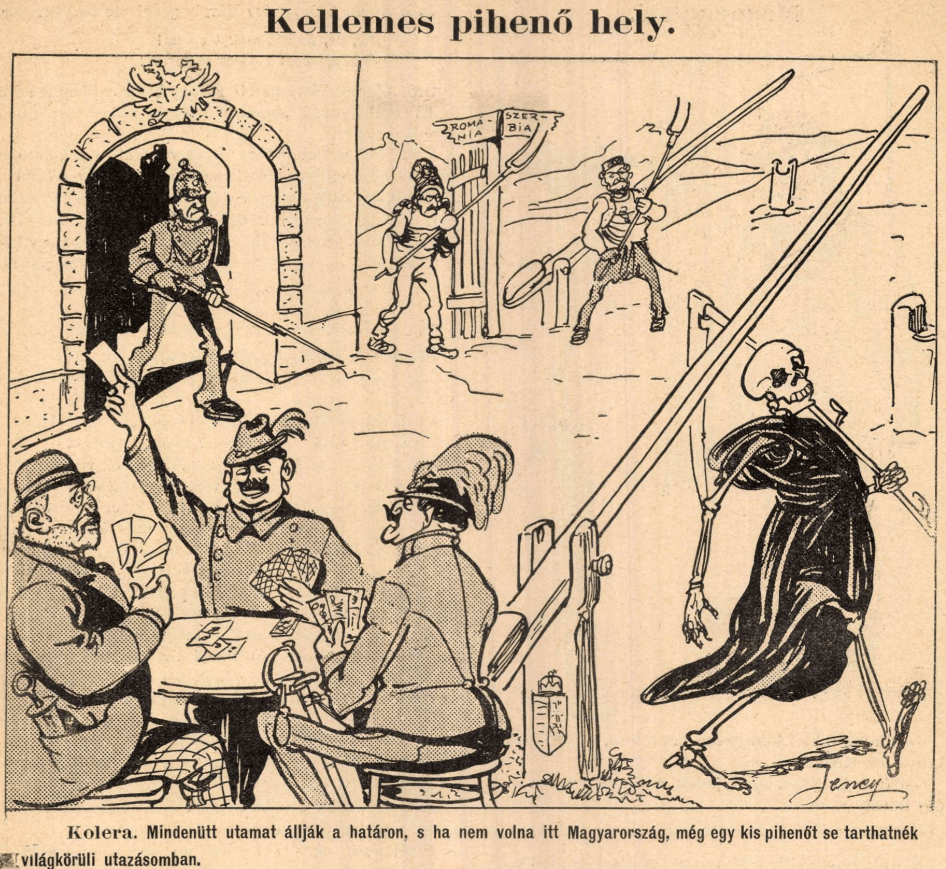

Cholera: “They block my path at the border everywhere, and if it weren’t for Hungary, I wouldn’t be able to take a break from my trip around the world.”

(Bolond Istók, Budapest, 1910) Let’s hope Mr. Emergency Decree can appreciate this kind of epidemic humor.

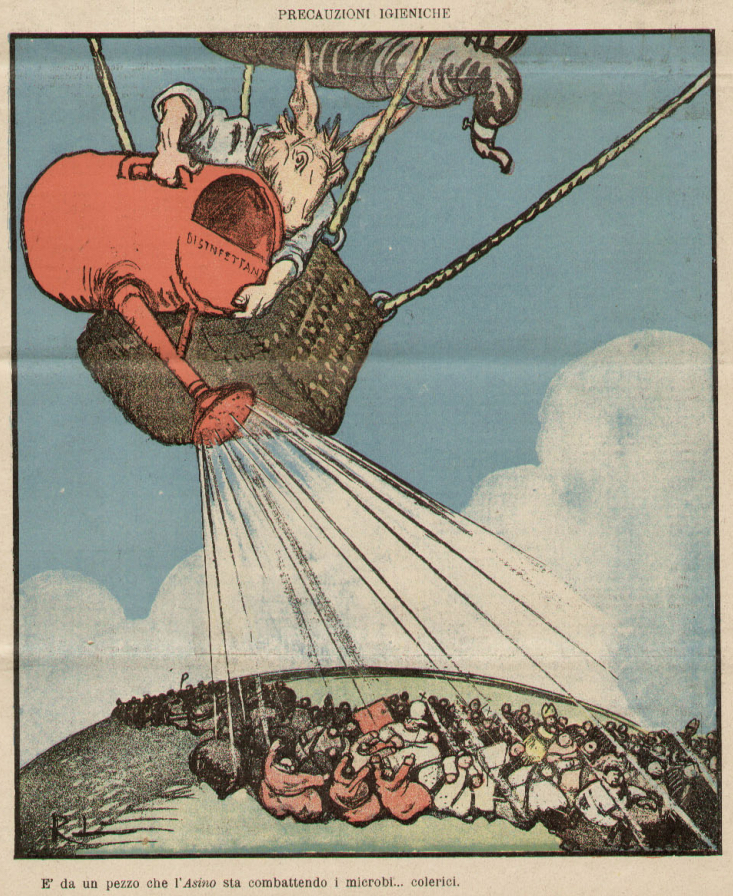

Really wandering beyond my ken here, but I find this image from the Italian satirical magazine L’Asino rather amusing. The eponymous mascot is pouring disinfectant on what seems to be a very clerical populace below. The caption reads, “It has been a long time that The Ass has been fighting against microbes… cholera microbes.” (I imagine there is word play on the sense of “choleric” here, but I don’t speak Italian.) The magazine was stridently anticlerical, and the winking implication is that it has been doing battle with metaphorical contagions, while cholera (the sixth pandemic then touching mainly the easternmost portions of Europe) was a literal latecomer.

(L’Asino, Rome, 1910)

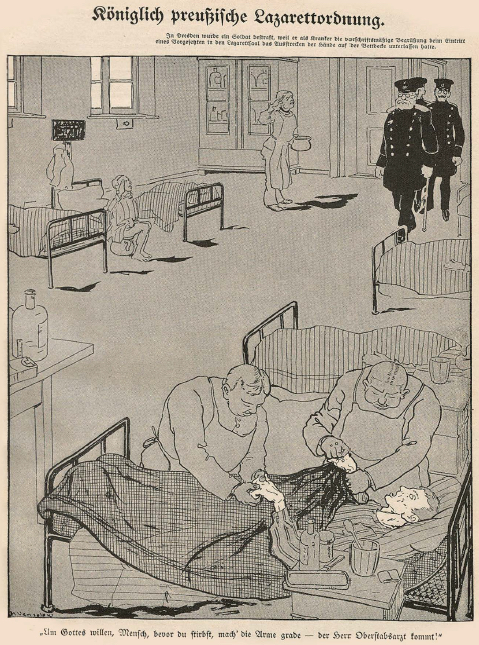

“In Dresden a soldier was fined because while a patient he had failed to salute in the regulated fashion at the entrance of a superior officer in the hospital ward and left his hands on the bedcovers.”

(Der wahre Jacob no. 616, Stuttgart, 1910)

“For God’s sake, man, before you die, straighten your arm — the senior staff physician is coming!”

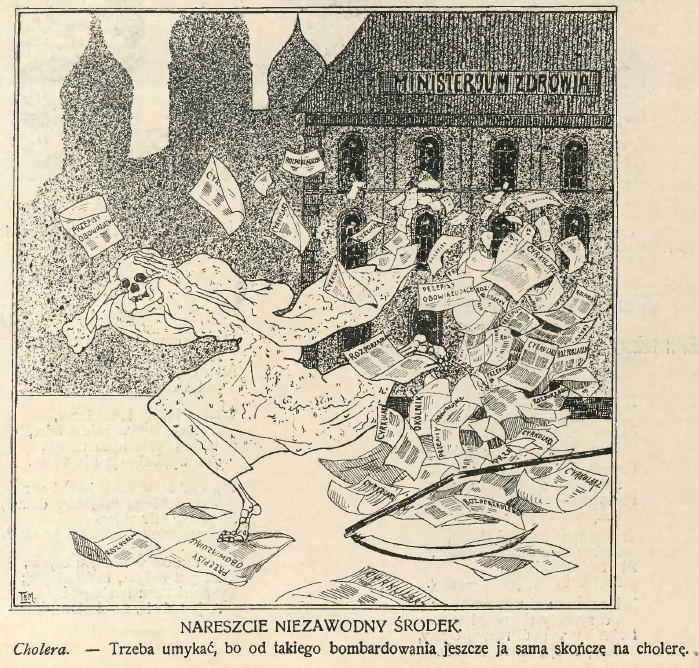

Russian Imperial Ministry of Health issuing flood of directives.

Cholera [angel of death]: “I have to get out of here, because even I will come to an end with cholera from such a bombardment.”

(Polish satirical magazine Mucha, Warsaw, 1910)

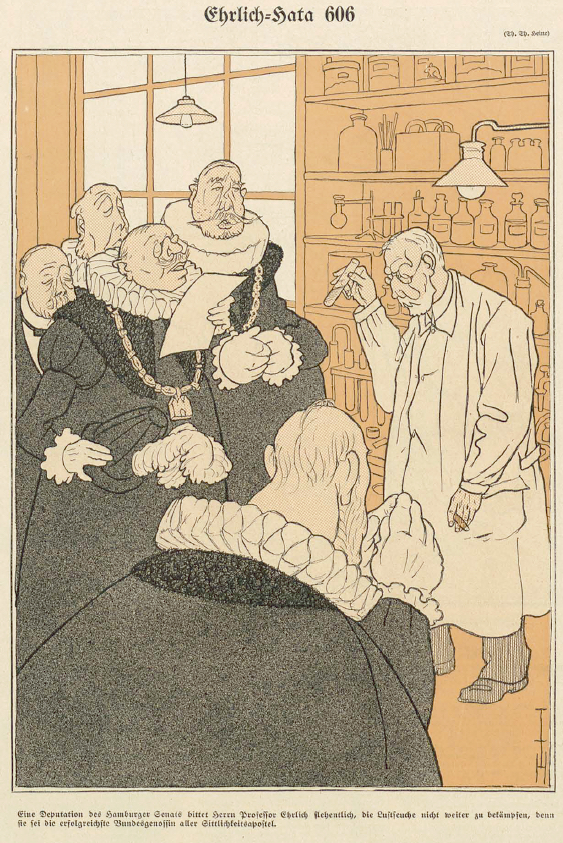

German satirical magazine Simplicissimus, 1910. A deputation of the Hamburg Senate implores Professor Ehrlich not to do battle with venereal disease any longer, for it is the most successful ally of all apostles of morality.

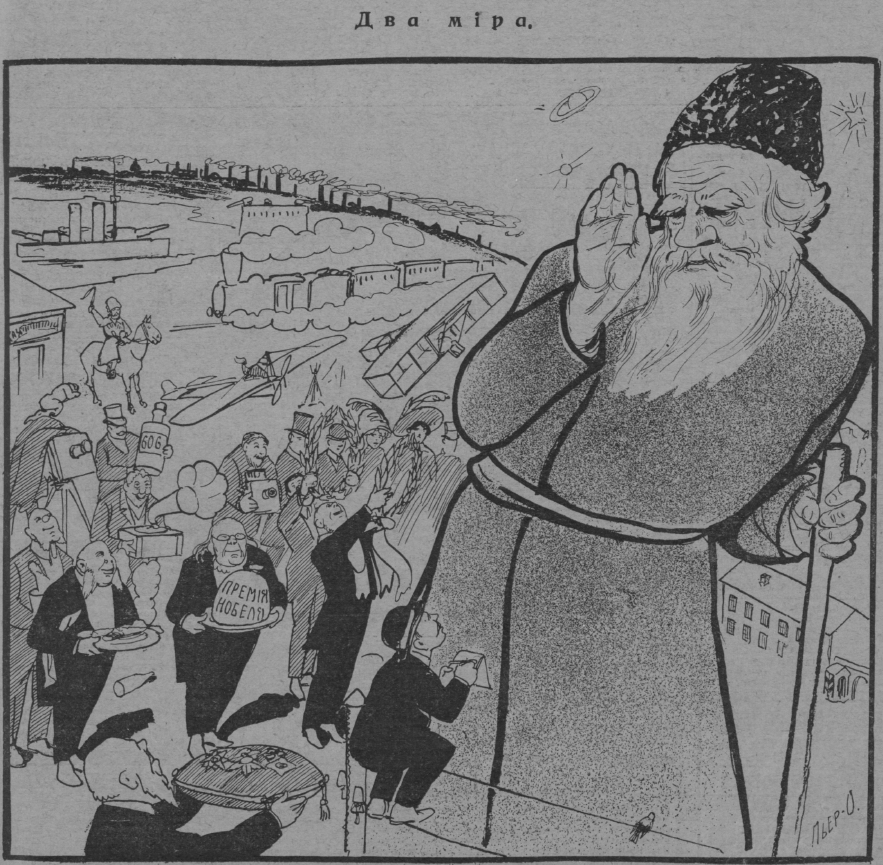

This image appeared in the Russian weekly magazine Ogonek (no. 45) on the eve of Leo Tolstoy’s death in 1910. Russia’s most famous anti-modernist is depicted turning away from the benefits and blandishments of the modern world. What is the connection between this image and our ongoing epidemic theme? (Hint: not the waiter with the tray labeled “Nobel Prize.” See this post for the answer.)

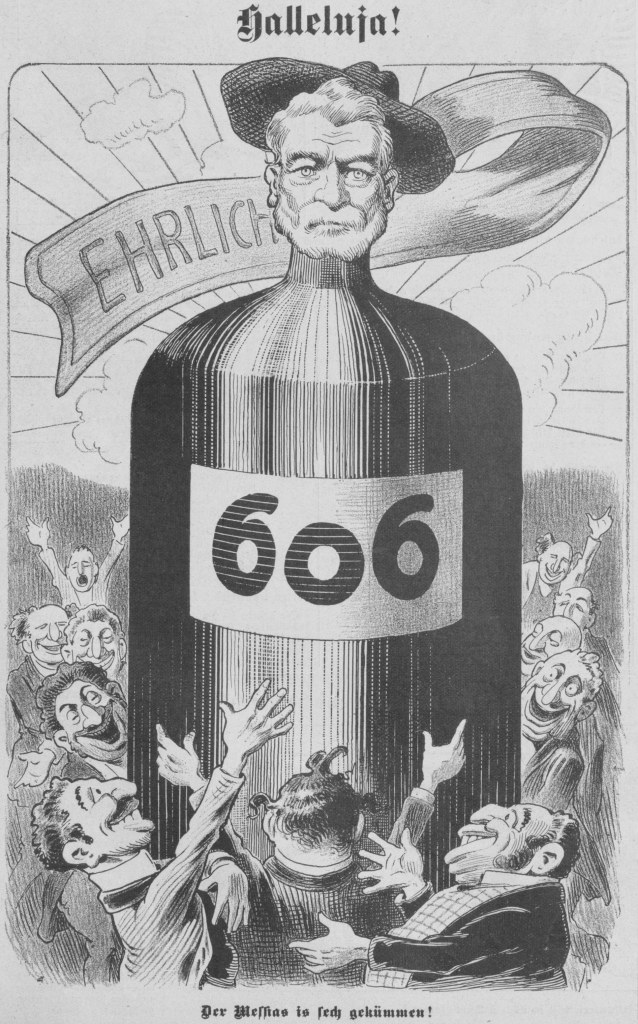

In 1910 German bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich became world famous when Hoechst AG began marketing Salvarsan, or “compound 606,” the first organic anti-syphilitic drug. Ehrlich’s laboratory colleague Sahachiro Hata first noted its toxicity to the syphilis spirochete, but Ehrlich’s “magic bullet” strategy for fighting epidemic diseases was what captured public attention. (Kikeriki, 1910) If you look carefully at this Tolstoy image from another post, you will see that Salvarsan is the connection.

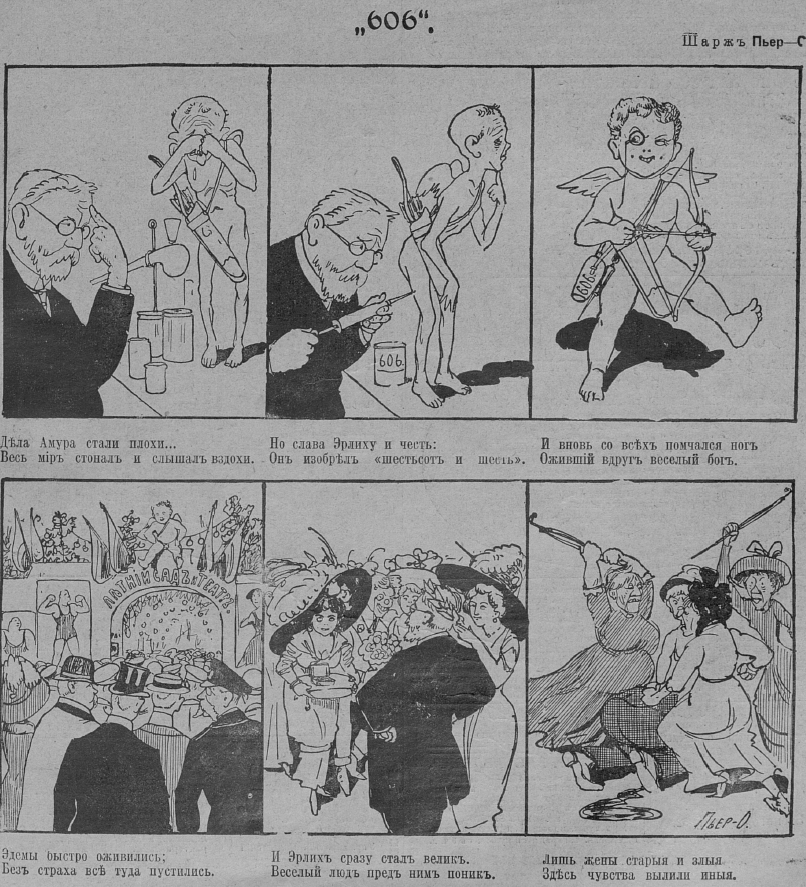

Ode to Paul Ehrlich’s “compound 606,” the magic bullet against syphilis.

Cupid’s affairs were in decline…

The whole world groaned and heard his sighs.

But glory and honor to Ehrlich:

He invented “six hundred and six.”

And suddenly back on his feet again

The merry deity was revived.

Pleasure spots quickly revived;

Everyone headed there without fear.

And Ehrlich immediately became great.

People gaily bowed before him.

Only old and malicious wives

Unleashed other feelings here.

(Ogonek no. 31, 1910)

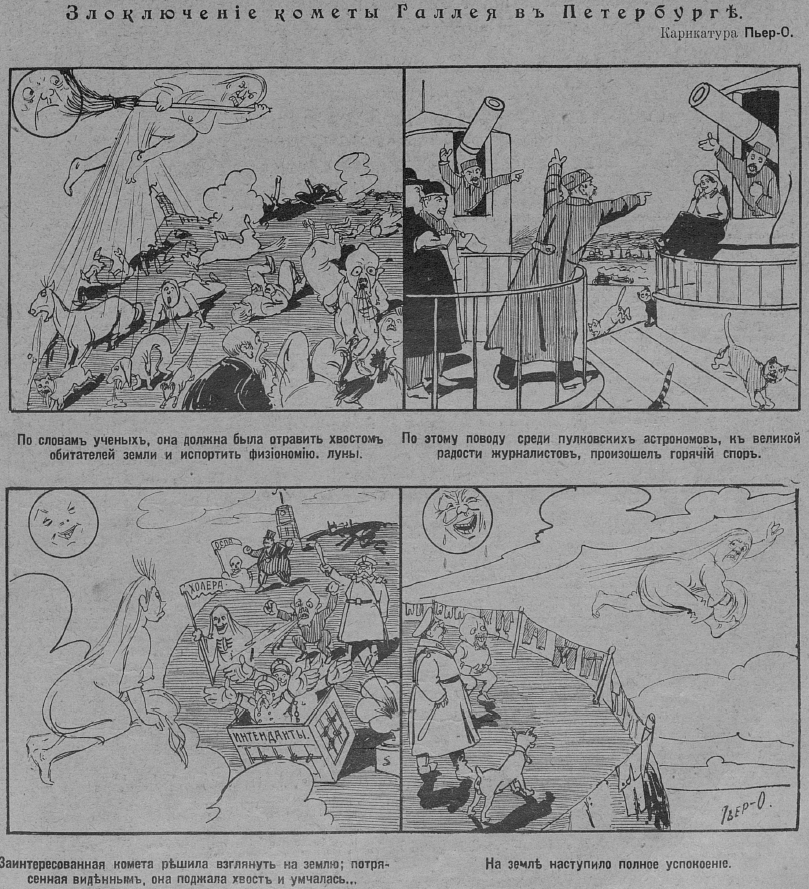

According to scientists, she was supposed to have poisoned the inhabitants of the earth with her tail and ruined the shape of the moon.

In this regard there was a heated debate among the Pulkovo astronomers, to the great joy of journalists.

Her interest piqued, the comet decided to take a look at the earth; shocked by what she saw [cholera, smallpox, quartermasters, gramophones], she pulled in her tail and sped away…

Complete calm settled upon the earth.

(Ogonek no. 20, 1910)

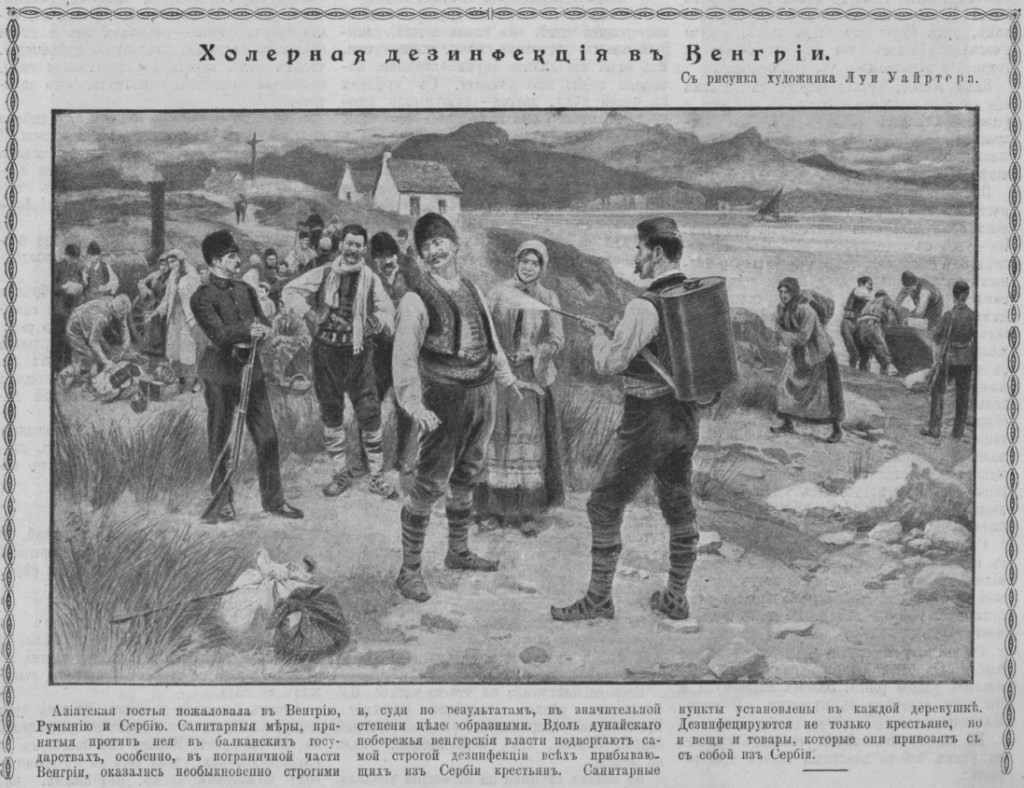

This image by the Scottish illustrator Louis Whirter was reprinted in the Russian magazine Ogonek no. 50 in 1910, but I have not been able to find anything further about its provenance. From the accompanying text: The Asian visitor (i.e., cholera) is welcomed to Hungary, Romania, and Serbia. Public health measures undertaken against it in the Balkan states, especially along Hungarian border areas, have been exceptionally strict, and judging by the results, quite expedient. Along the banks of the Danube the Hungarian authorities subject all arriving peasants from Serbia to strict disinfection.

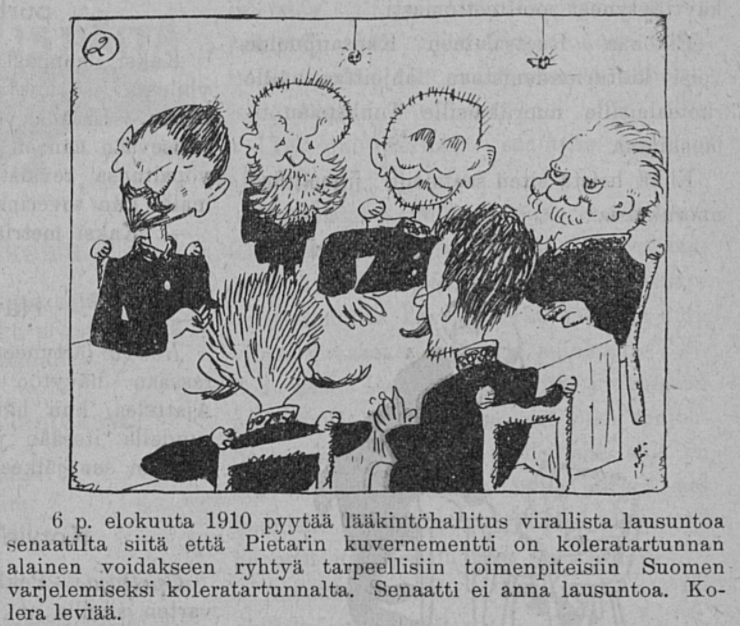

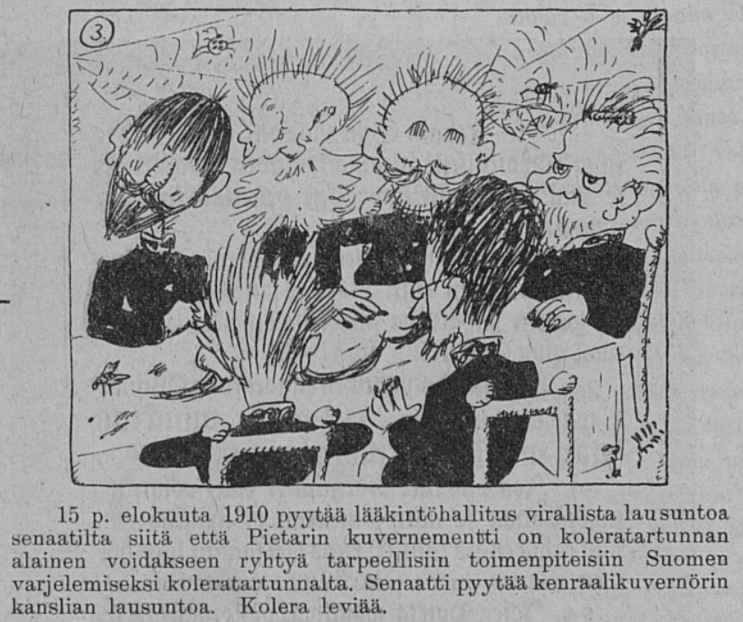

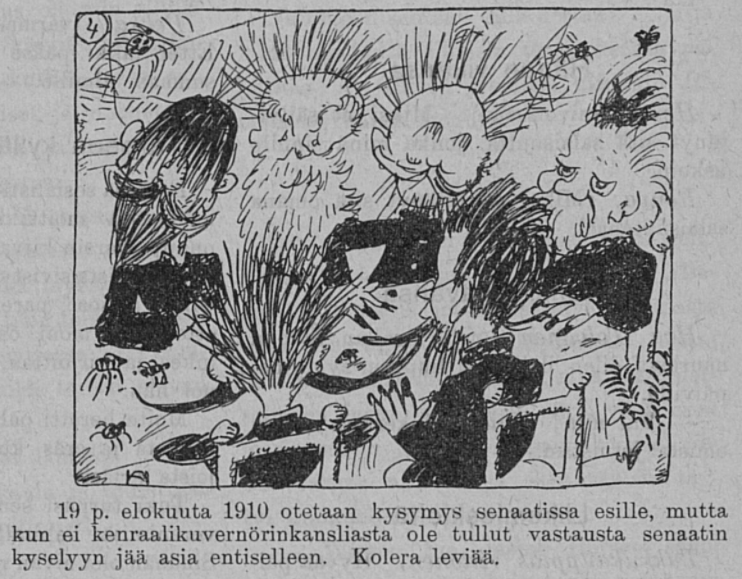

A Finnish cartoon from 1910 mocking the inaction of the Russian Imperial government during a cholera epidemic. (Tuulispää)

First panel: “On July 9, 1910, the Medical Board issued an official statement from the Senate that the St. Petersburg District was under cholera infection, in order to be able to take the necessary measures to protect Finland from cholera infection. The Senate does not issue an opinion. Cholera spreads.”

Fourth panel: “On August 19, 1910, the issue is raised in the Senate, but when the Office of the Governor-General does not receive an answer to the Senate’s inquiry, the matter remains as before. Cholera spreads.”