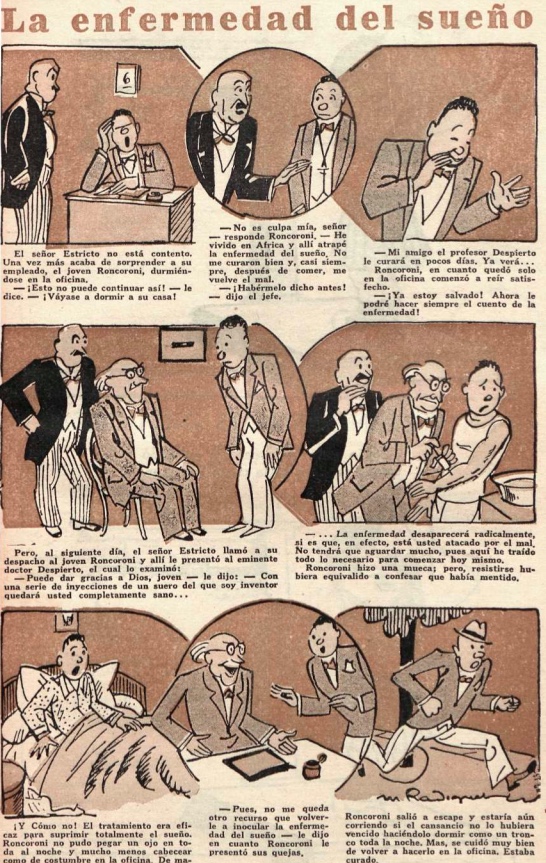

A sleeping sickness cartoon that is actually more about workplace discipline.

(Caras y caretas, Buenos Aires, 1936)

A sleeping sickness cartoon that is actually more about workplace discipline.

(Caras y caretas, Buenos Aires, 1936)

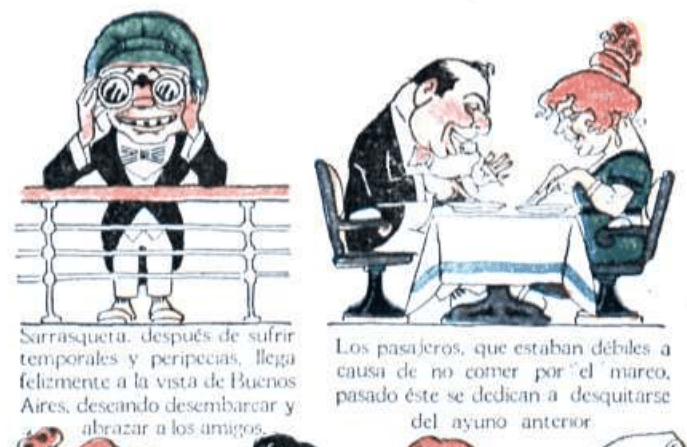

A tale from Caras y caretas, Buenos Aires, 1920.

Sarrasqueta, after suffering storms and tribulations, arrives happily at the sight of Buenos Aires, eager to disembark and embrace his friends.

The passengers, who were weak from not eating on schedule, now dedicate themselves to making up for the previous fasting.

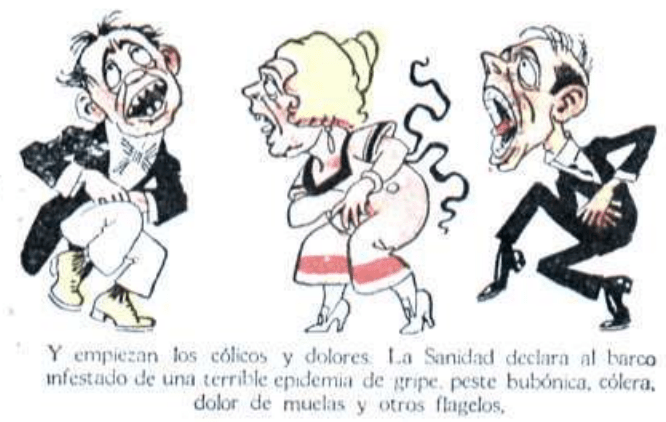

And the cramps and pains begin. The Health Department declares the ship infected with a terrible epidemic of influenza, bubonic plague, cholera, toothache, and other scourges..

The choir of doctors orders the passengers to undergo a thorough health inspection and rigorous quarantine. As if counting sheep, they first order the ladies to parade before them at great speed to check their tongues, and to be able to see a thousand an hour.

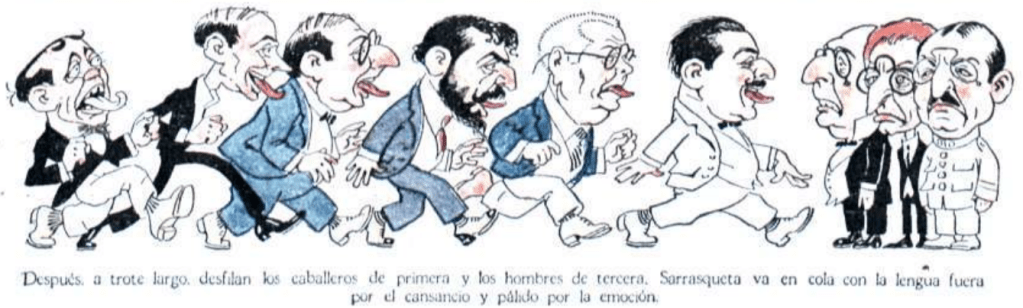

Then, at a slow trot, the first-class gentlemen and third-class men parade by the doctors. Sarrasqueta is in line with his tongue sticking out from exhaustion and pale with emotion.

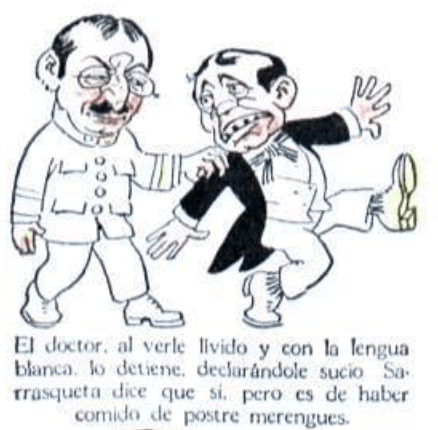

The doctor, seeing him pale and with a white tongue, stops him, declaring him unclean. Sarrasqueta accedes, but claims it is from having eaten meringues for dessert.

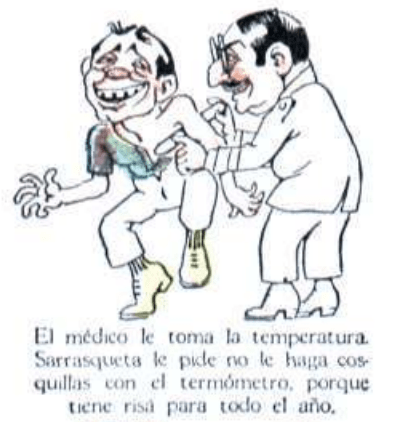

The doctor takes his temperature. Sarrasqueta asks him not to tickle him with the thermometer, because he’ll be laughing for the whole year.

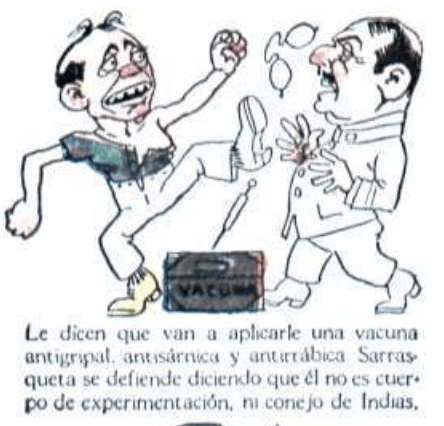

They tell him that they are going to give him a vaccine against flu, scabies, and rabies. Sarrasqueta defends himself by saying that he is neither a test body, nor a guinea pig.

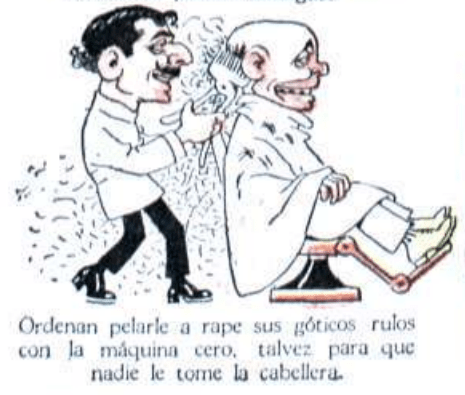

They order his gothic curls to be shaved off with the clipper, perhaps so that no one takes his hair.

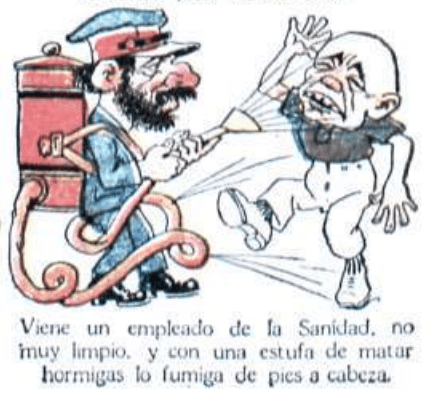

A public health employee arrives, not very clean, and with a fogger for killing ants he fumigates Sarrasqueta from head to toe.

They put the luggage in the disinfection oven, and they return it to him burnt to a crisp. And then they condemn him to undergo days of quarantine until they see the result of the vaccine.

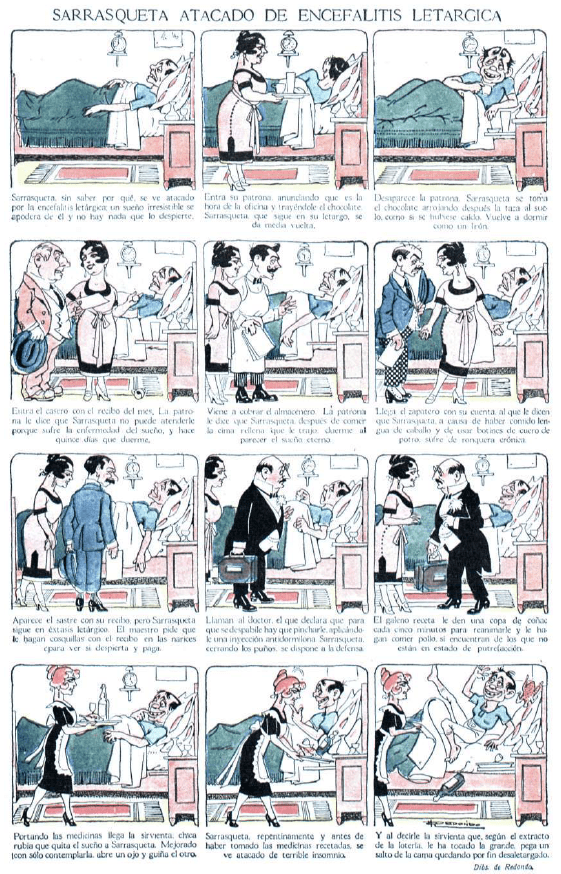

Sarrasqueta, without knowing why, is attacked by encephalitis lethargica: an irresistible slumber takes hold of him and there is nothing to wake him up.

His landlady enters announcing that it is office time and bringing him hot chocolate. Sarrasqueta, who is still in his lethargy, turns around.

The landlady disappears, Sarrasqueta takes the chocolate, then throws the cup on the ground, as if it had been broth. He goes back to sleep like a dormouse.

……

And when the maid told him that, according to the summary from the lottery, he had won the big one, he jumps out of bed and is finally delethargized.

(Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1920) (The available scan is rather low resolution, so it’s not worth breaking up into individual panels.)

(one panel of eight featuring this recurrent character)

Playing the gramophone with tango records and noisy military marches, applied to those who suffer from persistent migraine or encephalitis lethargica, awakens, rejoices, and relieves them.

(Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1922)

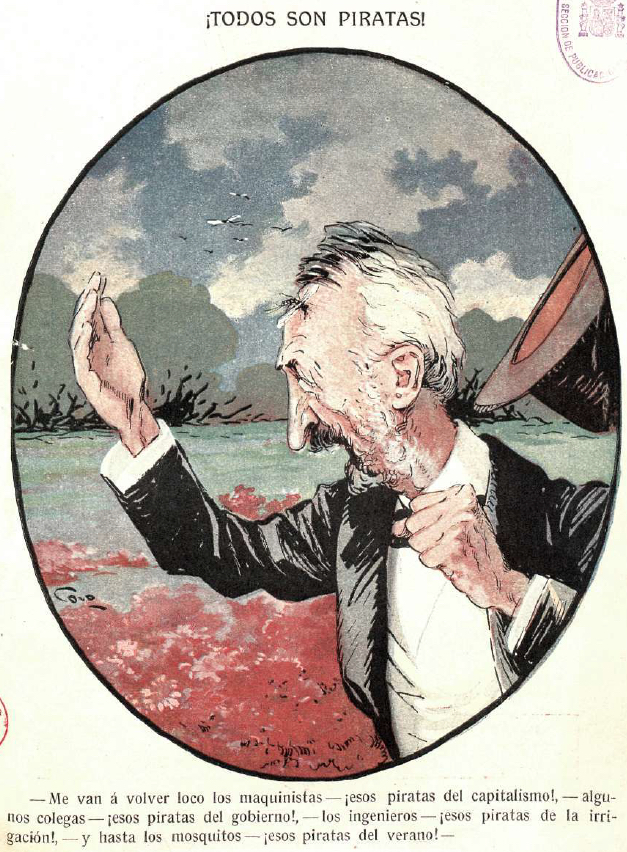

The machinists are going to drive me crazy – those pirates of capitalism! – some of the colleagues – those government pirates! – the engineers – those pirates of irrigation! – and even mosquitoes – those pirates of summer!

(Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1912) (A comical variant of Fitzcarraldo, you might say.)

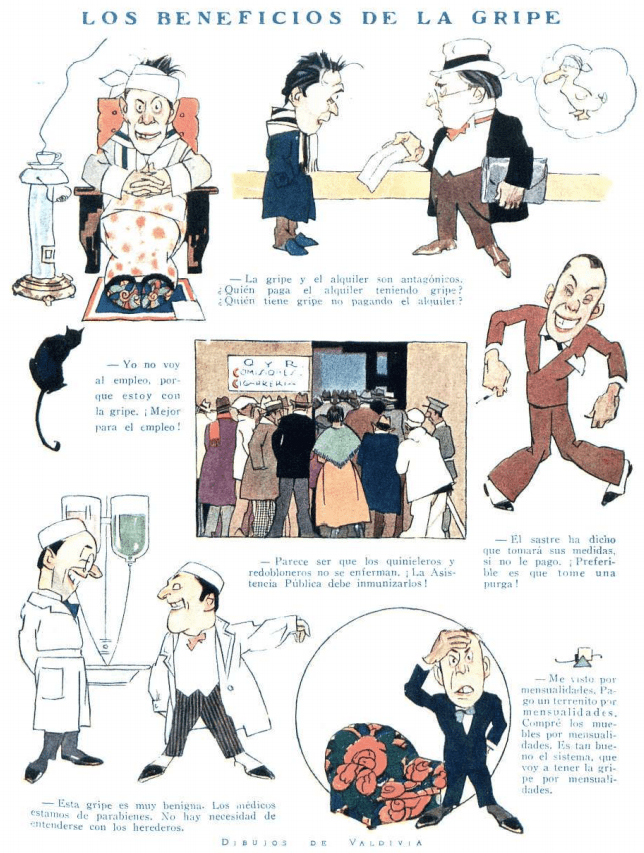

Flu and rent are antagonistic. Who pays the rent while they have the flu? Who has the flu without paying the rent?

I’m not going to work, because I’ve got the flu. Better for employment!

It seems that the bookmakers and the drummers do not get sick. Public Assistance must be immunizing them!

The tailor has said to take your measurements if I don’t pay. It is preferable to take a purge!

This flu is very benign. The doctors are in good spirits. There is no need to get along with the heirs.

I buy clothes on the installment plan. I buy a piece of land on the installment plan. I buy furniture on the installment plan. The system is so good that I will get the flu on the installment plan.

(Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1927)

(Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1918)

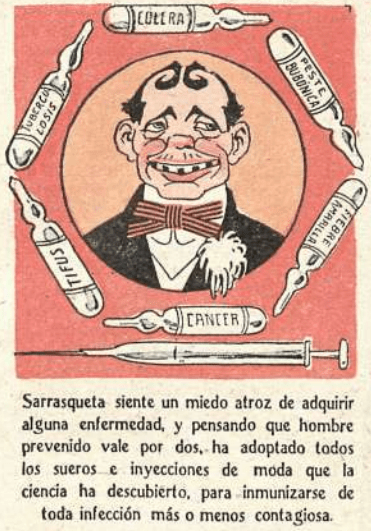

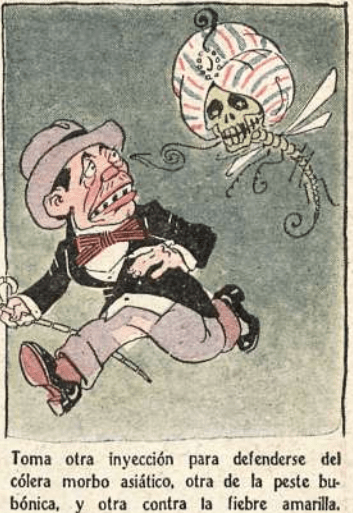

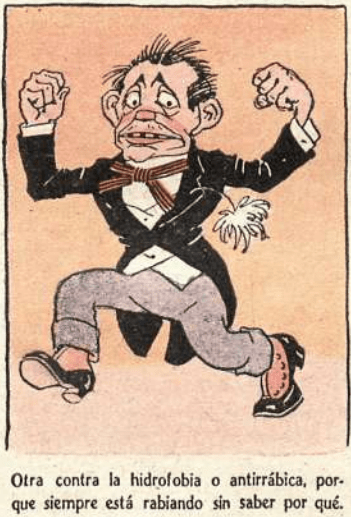

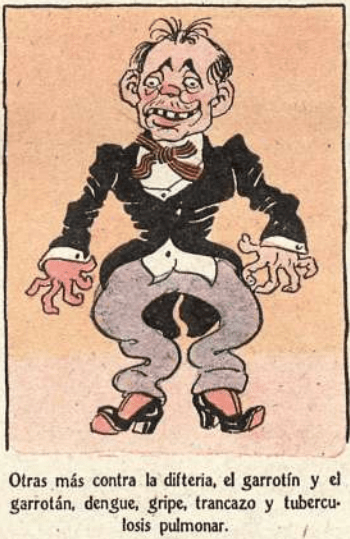

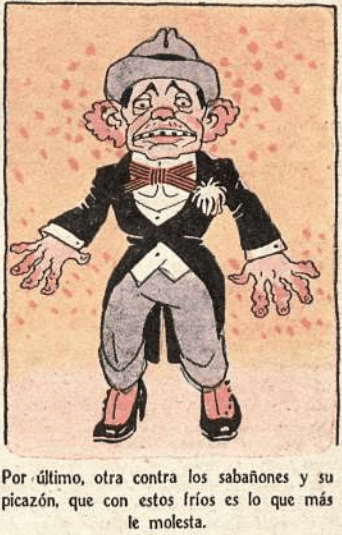

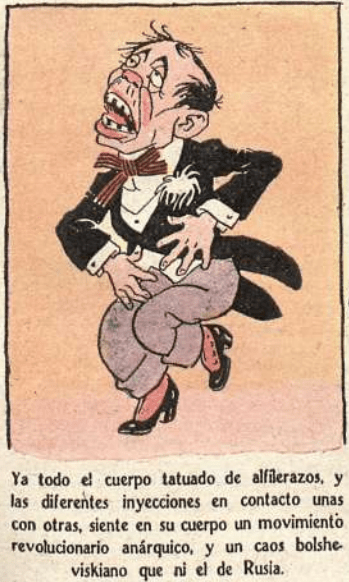

Sarasqueta feels an atrocious fear of acquiring some disease, and thinking that a protected man is worth two, he has adopted all the fashionable serums and injections that science has discovered, to immunize himself from any more or less contagious infection.

He starts by going to Public Assistance to get vaccinated and immunized from smallpox, both black and colored.

He takes another injection to defend himself from Asian cholera morbus, another against bubonic plague, and another against yellow fever.

Another against hydrophobia or anti-rabies, because he is always raging without knowing why.

Still others against diphtheria, flamenco, dengue, influenza, flu, and pulmonary tuberculosis.

Finally, another against the chilblains and their itching, which with these colds is what bothers him most.

With his entire body already tattooed with needles, and the different injections in contact with each other, he feels an anarchic revolutionary movement inside, and a Bolshevik chaos that is not the Russian one.

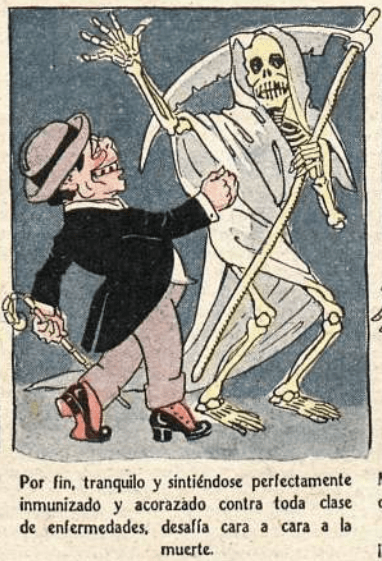

Finally, calm and feeling perfectly immunized and armored against all kinds of diseases, he defies death face to face.

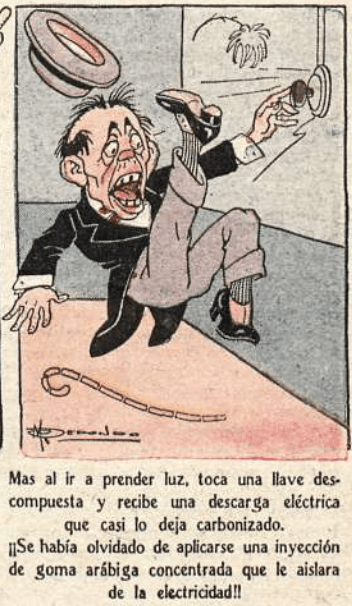

But when he goes to turn on the light, he touches a broken switch and receives an electric shock that almost leaves him charred.

He had forgotten to apply a concentrated gum acacia injection that would insulate him from electricity!

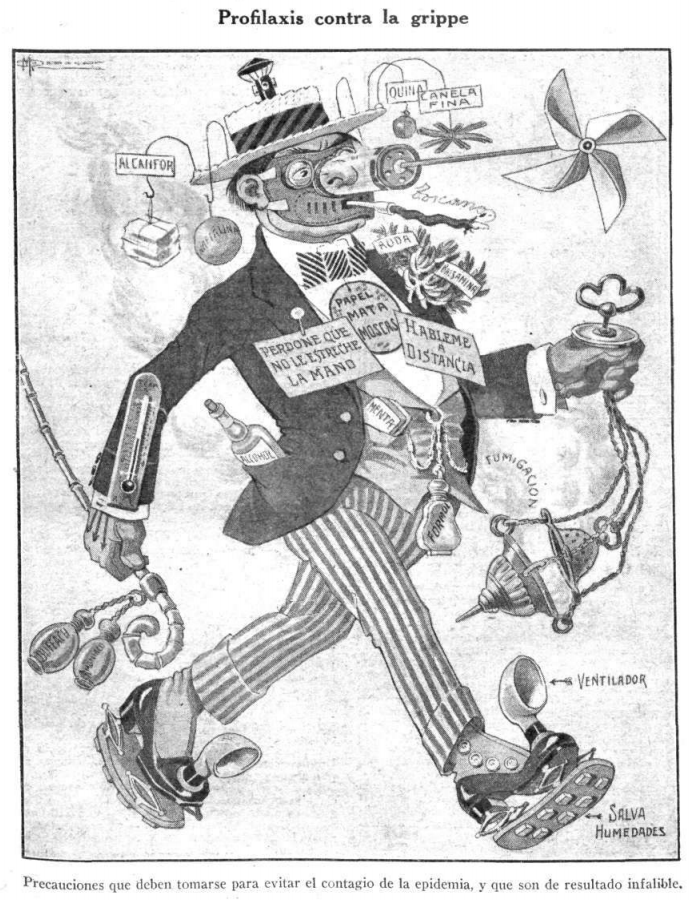

Precautions that must be taken to avoid the spread of the epidemic, and which offer a flawless result.

(Among the items affixed to him: camphor, naphthalene, quinine, cinnamon, “Sorry for not shaking your hand,” flypaper, “Please speak to me at a distance,” alcohol, mint, fumigation by censor, a ventilation device, and what I take to be pads for absorbing humidity. Having a thermometer always at the ready is a crowning touch.)

(Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1918) (Note the similarity to Jeremiah Fastidious from 1892)

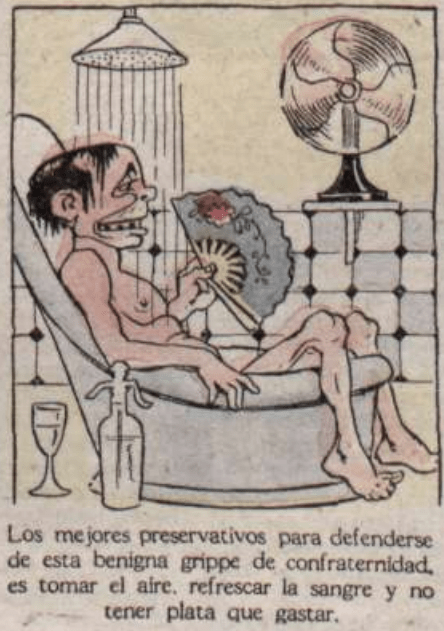

From Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1918.

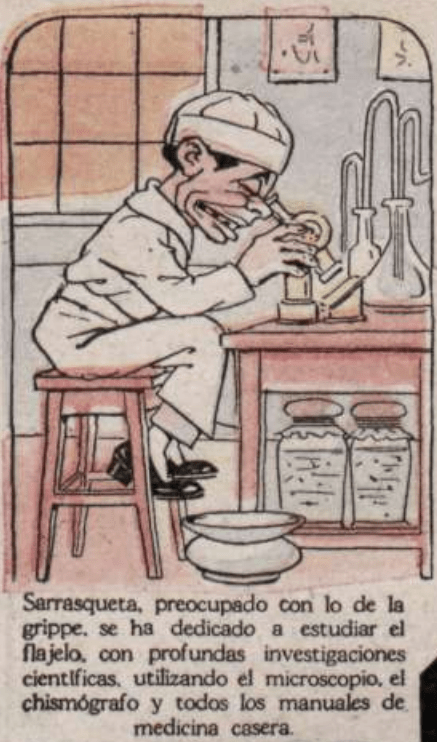

Sarrasqueta, concerned about the flu, has devoted himself to studying flagella, with deep scientific research, using the microscope, the gossip machine and all the manuals on home medicine.

After long experiments he has come to suspect that the flu is a Spanish pop singer, that she is making propaganda, and that she makes people sick with a glance from her eyes, attacking only weak, but well-heeled people.

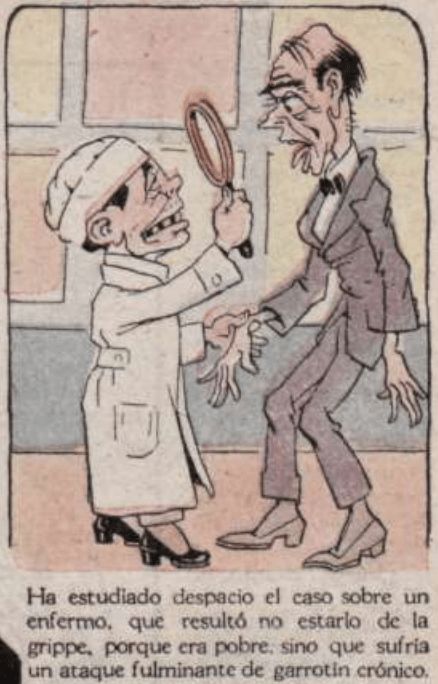

He has slowly studied the case of a patient who turned out not to have the flu, because he was poor, but suffered a sudden attack of chronic flamenco.

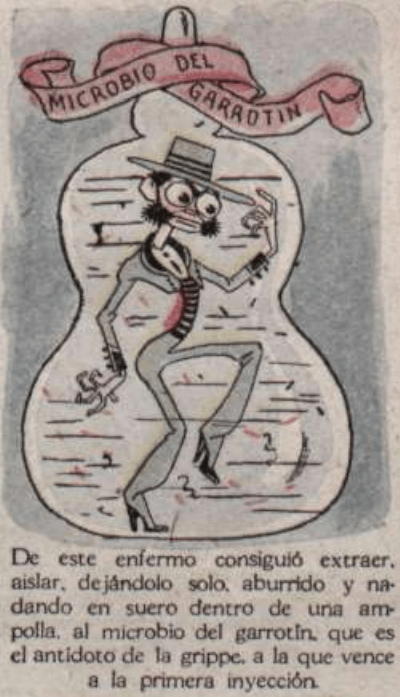

From this patient he managed to extract and isolate the flamenco microbe by leaving him alone, bored and swimming in serum in an ampoule, which is the antidote to the flu, defeating it with a single injection.

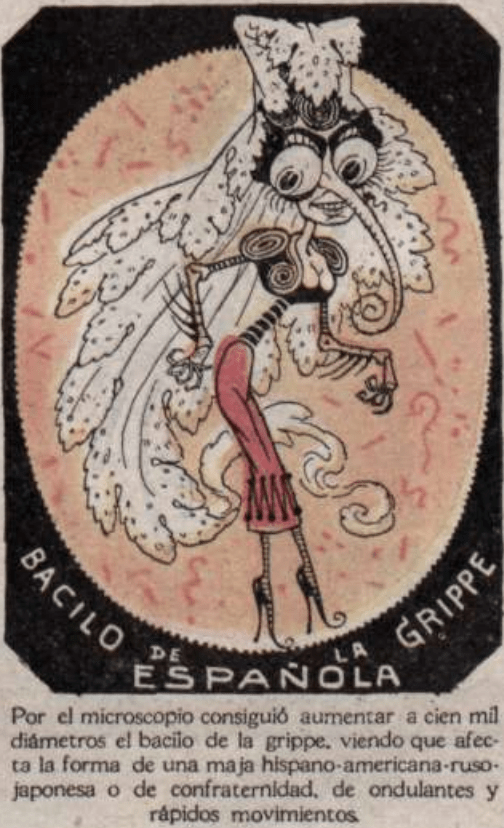

Using the microscope, he managed to magnify the flu bacillus to a hundred thousand diameters, seeing that it affects the shape of a pretty Spanish-American-Russian-Japanese or of confraternity, with undulating and rapid movements.

Once the flamenco serum is injected in the patient with the flu, such a gypsy dance is mounted between both bacilli that to calm the patient from his nervousness, one has to play the guitar for a while.

The symptoms of the disease are an increase in temperature, drum roll noises in the head, desire to dance, ending in the cries: Help! Protection! Mercy! Console me! (They are other pop singers)

The best protections to defend against this benign flu confraternity is to take the air, refresh the blood, and have no money to spend.

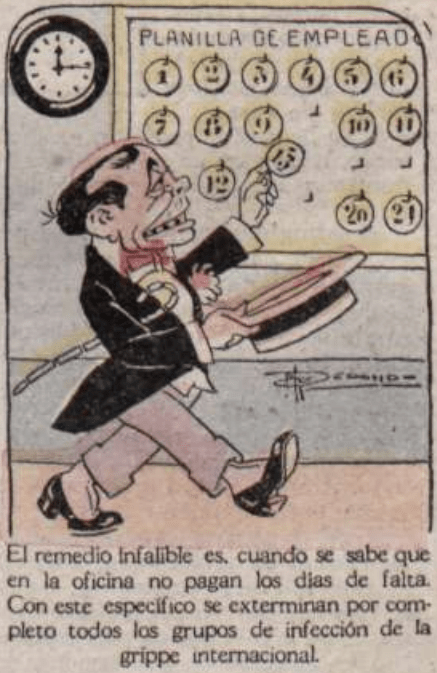

The infallible remedy is when it becomes known that they do not pay for the days lost at the office. With this detail, all the infection groups of the international flu will be completely exterminated.

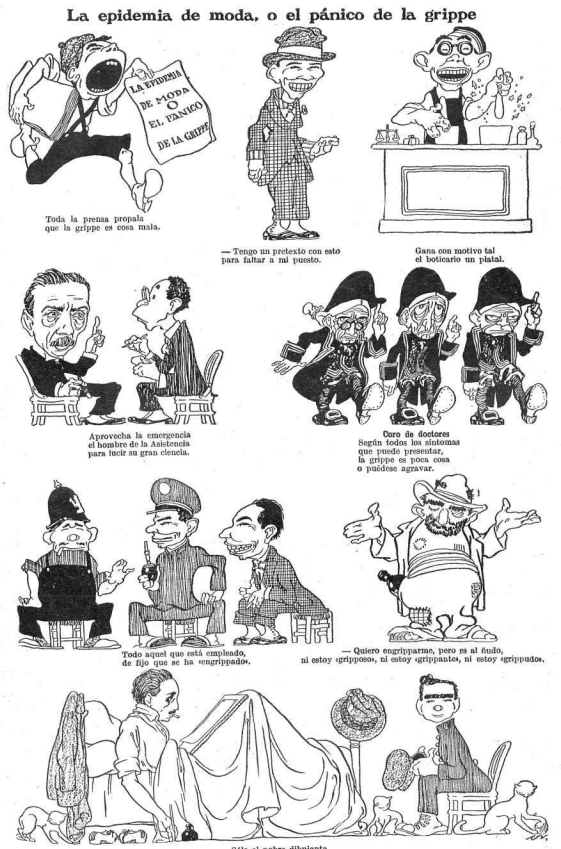

Though it has come to sound a little old-fashioned in English, it is still possible to refer to the flu as “grippe.” This Argentine cartoon is punning relentlessly on the senses of “grip” (e.g., inverting “in the grip of panic” in the title) and I will surely mistake some of the participles, but let’s give it a try.

“All the press is propagating the notion that the grippe is a bad thing. “With this I have a pretext to fail at my post.” For this reason the pharmacist is gaining a fortune. The man at Medical Aid takes advantage of the emergency to show off his great science. Chorus of doctors: according to all the symptoms that it can present, the grippe is a minor thing or it can be aggravated. Anyone who is employed has, of course, been “in the grip.” “I want to get a grip on myself, but it is in vain, I am not “grippy,” nor am I “gripping,” nor am I a “gripper.” Only the poor cartoonist is the constant victim of the general contagion, and works at all times, whether he is well or he is ill.”

(Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1918)

Then they say that I develop among the crowds; and as soon as the people took to the streets to celebrate the triumph of the allies, I had to be moved!

(Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1918)

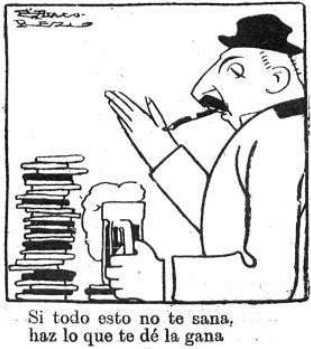

Two panels from a dozen on ways to fight the flu.

(Caras y caretas, Buenos Aires, 1919)

Don’t go out at night. There are several ways to play solitaire.

If all this does not heal you, do what you want.

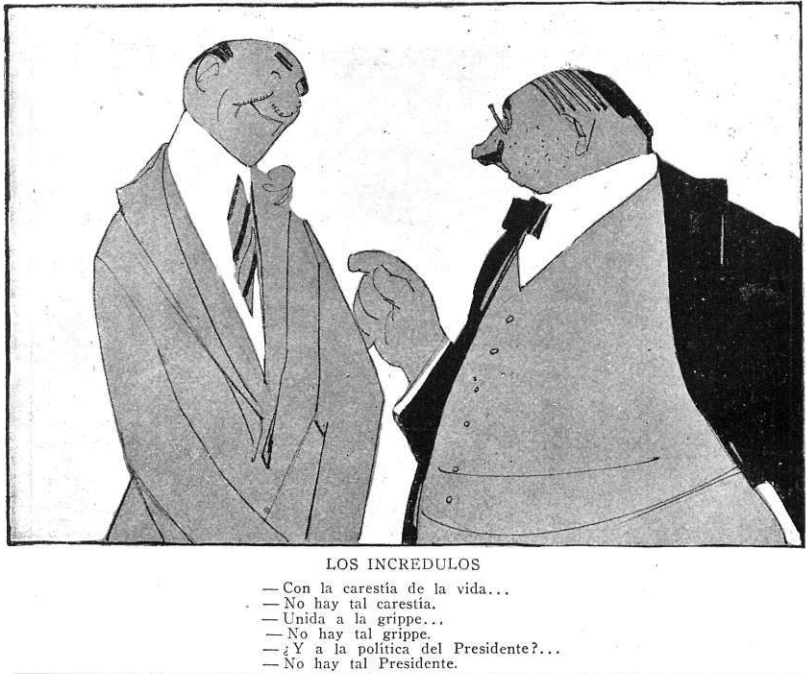

“With the dearth of life …”

“There is no such dearth.”

“Attached to the flu…”

“There is no such flu.”

“And to the President’s policy?…”

“There is no such President.”

(Caras y caretas, Buenos Aires, 1919)

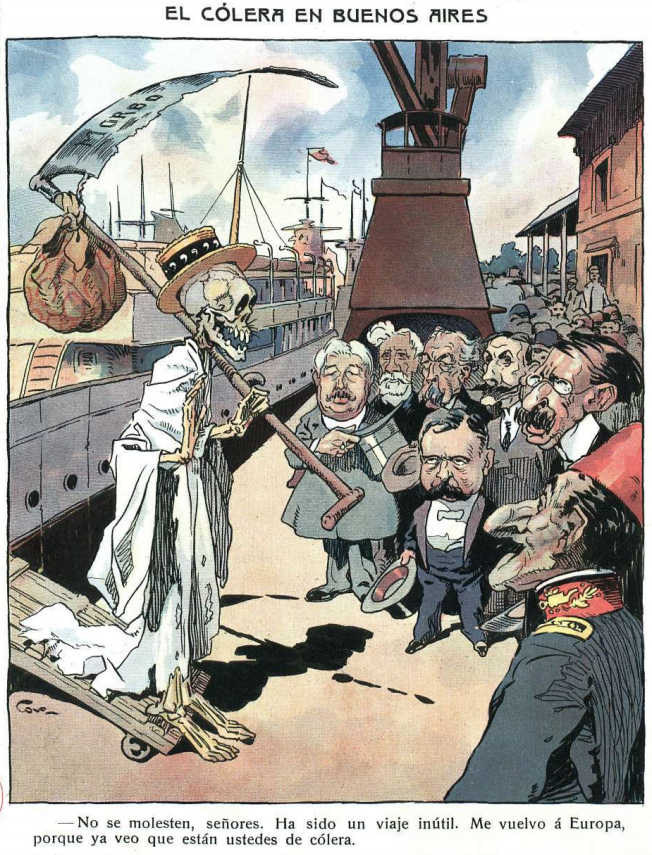

“Don’t bother, gentlemen. It has been a pointless journey. I am returning to Europe, because I see that you are angry.” (Punning again on cholera/choler, I believe.)

(Caras y caretas, Buenos Aires, 1908)

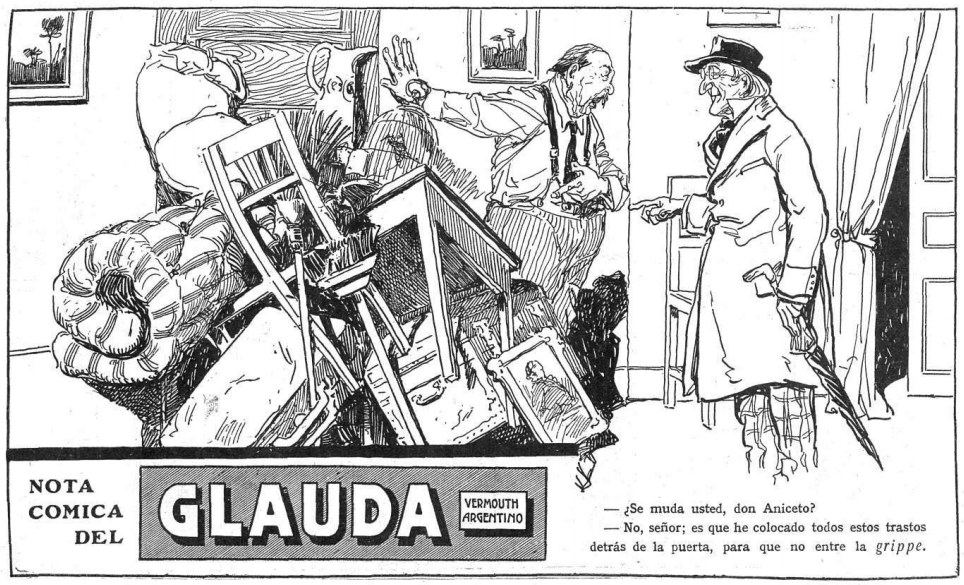

Comic notes sponsored by Glauda Vermouth in Argentina during the flu pandemic of 1918.

“And in this room, which is twice the size, are they also from the flu?”

“No, sir; those are from the group.” (Sorry, I don’t know how to convey the pun.)

(Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1918)

“Are you moving, Don Aniceto?”

“No, sir; it’s just that I’ve put all this junk behind the door, so the flu doesn’t get in.”