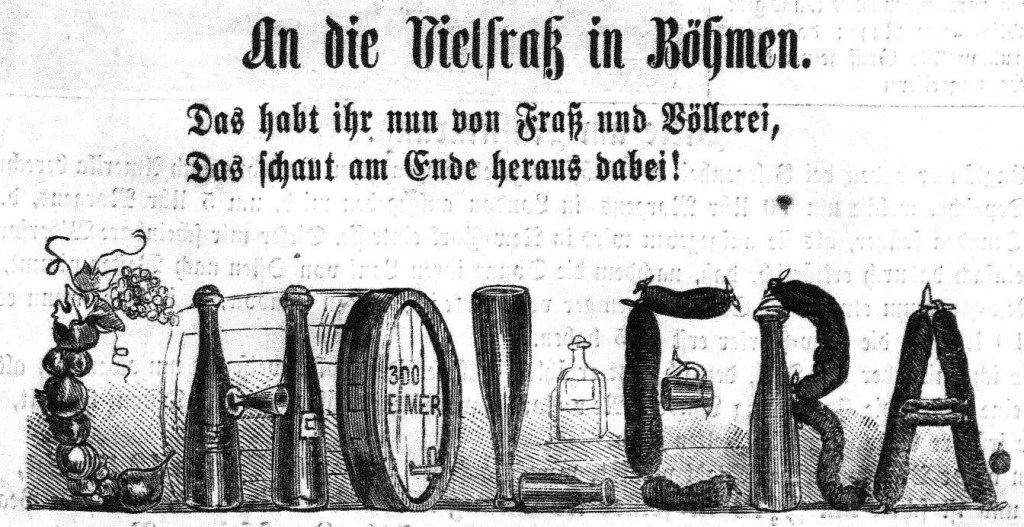

You got it from gulping and gluttony,

It shows in it in the end!

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1866)

You got it from gulping and gluttony,

It shows in it in the end!

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1866)

This one takes some unpacking, but it is a marvelous example of epidemic disease fueling conspiracy theories that in turn invite the satirist’s attention. In the spring of 1854 the imperial Russian general Prince Mikhail Gorchakov led troops over the Ottoman frontier at Silistra (present-day northeastern Bulgaria), accelerating the Crimean War. The Russian siege did not go well, and in late April Prince Ivan Paskevich (Paskiewicz), the Ukrainian-Cossack military figure notorious for crushing the Polish rebellion in 1831 and presiding at the surrender of the Hungarians during the 1848 revolution, took charge. In early July following a battlefield mishap he was in turn replaced by Prince Gorchakov, though Paskevich remained the active senior commander. Several weeks later Paskevich ordered general withdrawal, not least under diplomatic pressure from Austria, which threatened to join the conflict. The talented diplomat Prince Alexander Gorchakov, who would become Foreign Minister several years later and was a distant cousin of the general, had been dispatched as ambassador to the Habsburg Court only weeks before this cartoon was published.

“Piefke” was a mildly derogatory Austrian term for Prussians. Here we find two self-important Berliners in conversation, clearly animated by events related to the Crimean War. The image itself was recycled whenever the two characters were featured in conversation about current events.

Piefke: “So we still don’t know for sure about the cause of the fire in Schottenhof?” (One week earlier the massive Schottenhof complex in the northwest corner of the inner city had been badly damaged by a fire on the roof, an event that warranted a visit by the emperor.)

Pufke: “Yes, yes! You already know –“

Piefke: “Well, what?”

Pufke: “Don’t you know who is to blame for the grapevine disease –” (A Styrian observer took this to be Uncinula necator, a powdery mildew first identified by British gardener Tucker in 1845. The Phylloxera blight noticed in French vineyards in 1853 was then spreading rapidly. The definitive cause had not yet been identified; hence the generic name for the disease.)

Piefke: “No!”

Pufke: “And what about cholera?” (In the midst of the third cholera pandemic, this was the year physician John Snow famously identified the water-borne source of the outbreak on Broad Street in London.)

Piefke: “Not that either.”

Pufke: “Listen, Piefke! You are terribly ignorant. Now you see, Prince Gorchakov has the grapevine sickness on his conscience; for he turned the grapes at Kalafat and Silistra sour. Prince Paskevich unleashed cholera on the world; for when he did not succeed in taking Silistra by a coup de main, he was full of anger [recall the misleading “choleric” association of the disease], and since then a general fury has raged through the lower intestines of Europe. Wasn’t it the Russians who tried to ignite the blaze of hatred and discord in the courts of Europe and Asia? But what they did at all the courts: they certainly did at the Schottenhof as well.”

(Der Humorist, Vienna, 1854)

This is one of the earliest readily available Austrian cholera cartoons. Founded in 1837 by the polymath Austrian Jewish journalist Moritz Gottlieb Saphir, Der Humorist only rarely featured cartoons in its early years. In any event, a cursory search did not turn up any cholera images from its recurrence during the 1848 revolution. With the appearance of Figaro in 1857 and Kikeriki in 1861 Der Humorist gradually increased the frequency of cartoons on its pages. In subsequent months there were indeed several more cholera cartoons in the Piefke and Pufke series.

Piefke: “Have you already taken a measure against cholera?”

Pufke: “Oh yes, as a rule I drink great amounts!” [punning on Massregel]

Piefke: “Tell me, do you keep your own diet during the cholera?”

Purke: “Of course.”

Piefke: “How?”

Pufke: “First thing in the morning grab your head and give yourself a slap on the face, so that you’re not afraid; then as a precaution slap all the members of your family. Then have a cup of coffee with three rolls. Then a dose of quinine. An hour later a fluffy pastry with Limoni and half a beer; then a Dover’s Powder. At 11am have goulash with dumplings with twenty drops of laudanum on top and so on until evening. To protect yourself from chills, have yourself warmed up by your creditors and wear a flannel bandage around your torso and a hot-water bottle.”

Piefke: “I know a better way.”

Pufke: “And?”

Piefke: “You have to deal with cholera like you do with paying debts.”

Pufke: “What does that mean?”

Piefke: “Don’t think about it at all!”

Piefke: “Tell me, dear Pufke, do you know which is the best servant in all of Vienna right now?”

Pufke: “No, which one?”

Piefke: “Cholera.”

Pufke: “Cholera? How so?”

Piefke: “Well, it stays around even if you keep treating it badly.”

Same image a week later for this text:

Piefke: “If it’s true that copper makes the best prevention against cholera: then who is the most protected?”

Pufke: “How can you ask? Obviously the publisher of our broadsheets; for they soak up almost entirely copper money.”

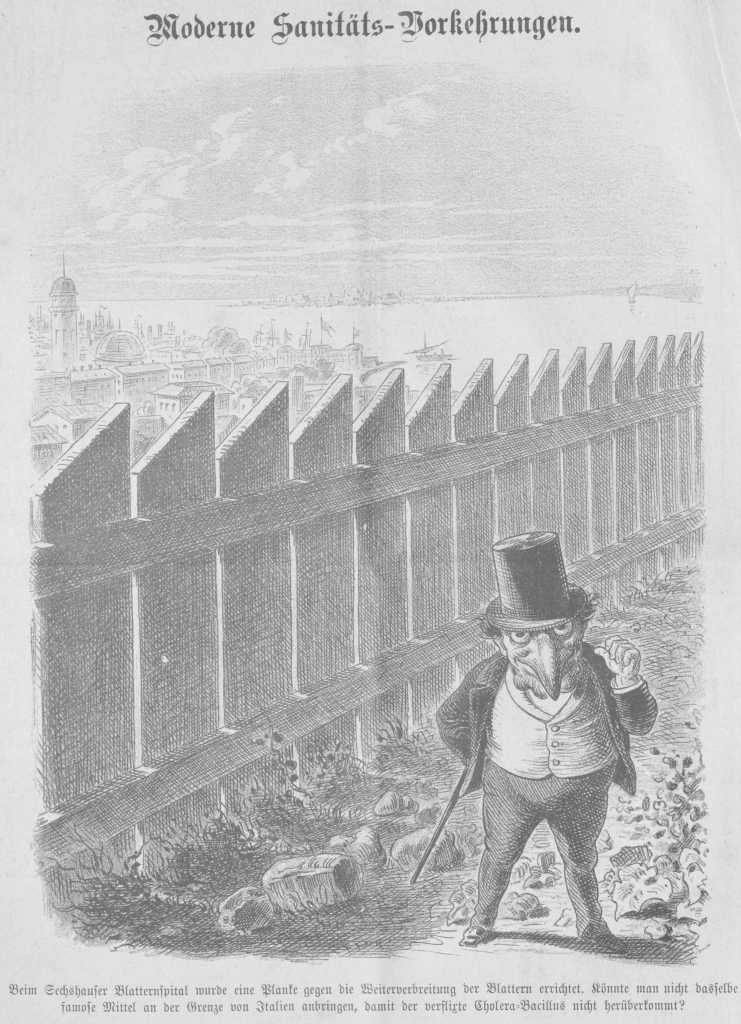

At the Sechshaufer Smallpox Hospital a barrier was erected against the spread of smallpox. Couldn’t one install the same splendid means along the border with Italy, so that the confounded cholera bacillus does not come over here?

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1886) (And in a similar vein.)

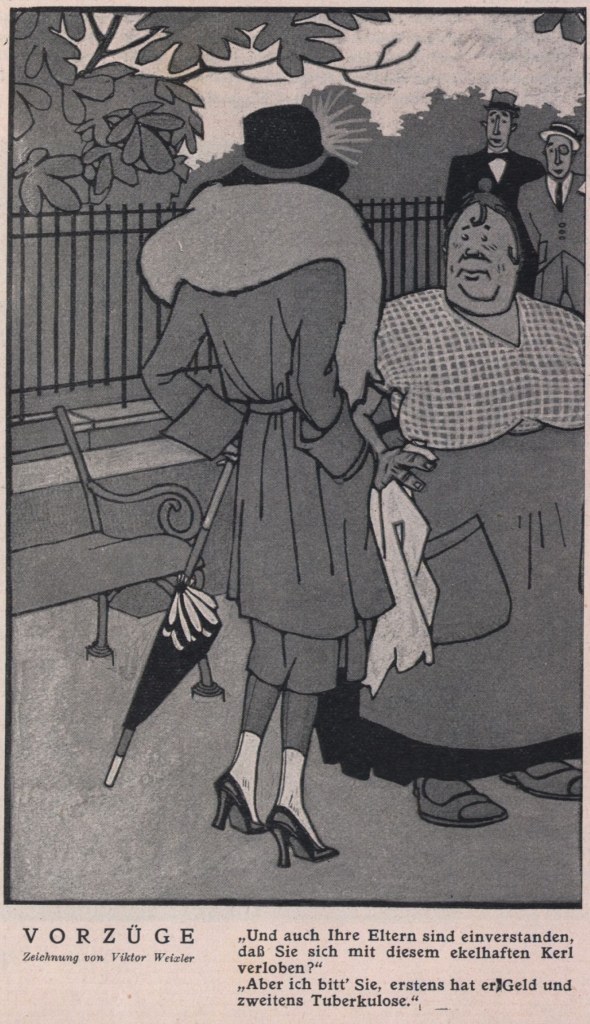

“And your parents are also in agreement that you are engaged to this disgusting fellow?”

“But please, first of all, he has money, and second, tuberculosis.”

(Die Muskete, Vienna, 1933)

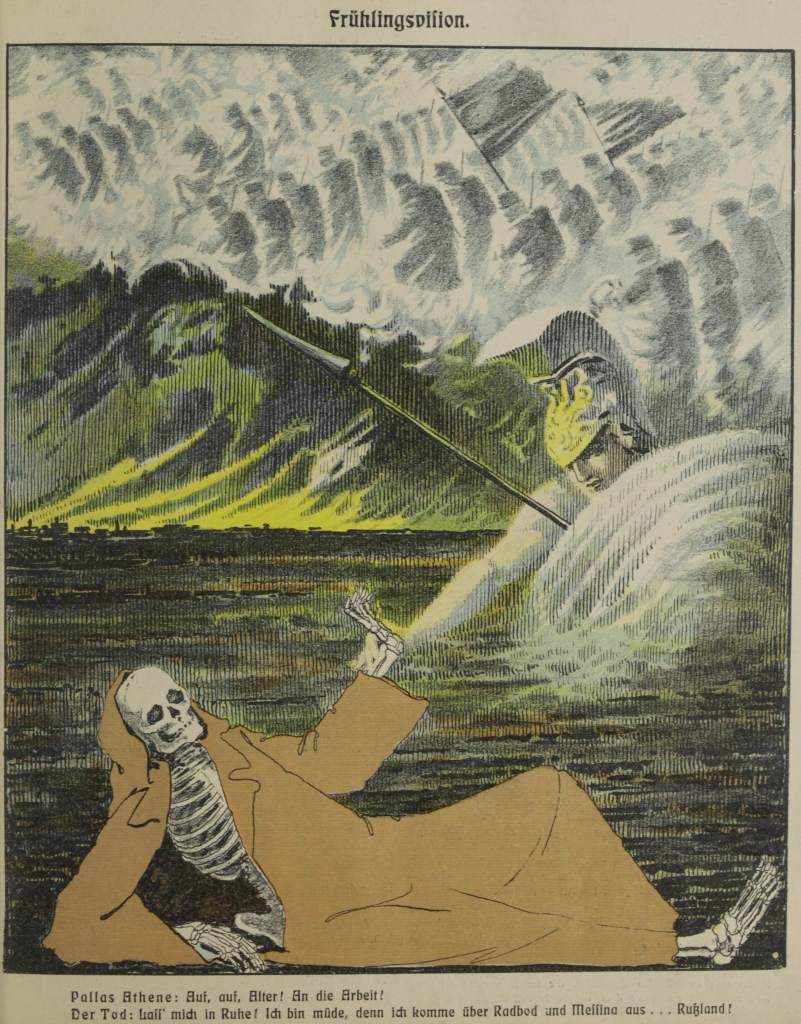

Pallas Athena: “Get up, get up, old man! Off to work!”

Death: “Leave me alone! I’m tired, I’m passing through Radbod and Messina… from Russia!”

(Die Glühlichter, Vienna, 1909)

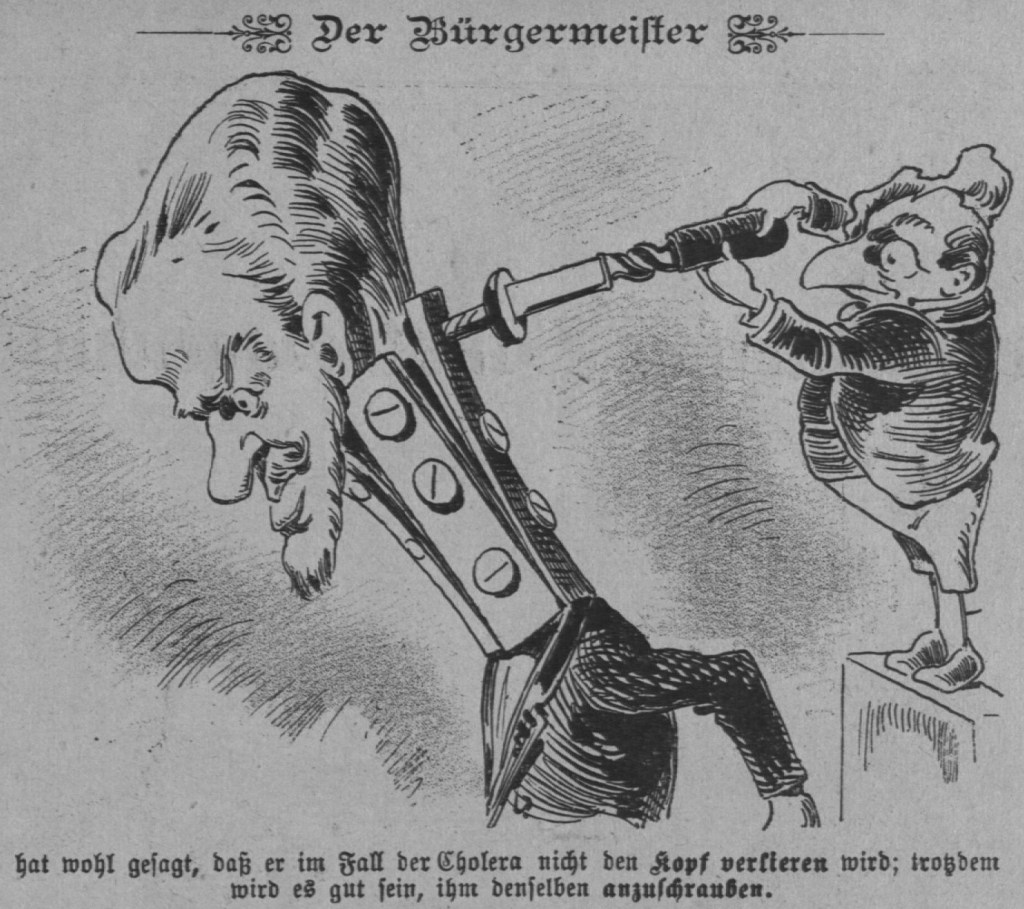

Johann Prix, b. 1836, member of the Progressive Party; presided over the legal expansion of the Vienna municipality. “The major did say that he would not lose his head in case of cholera; it would nonetheless be good to tighten his screws.”

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1892)

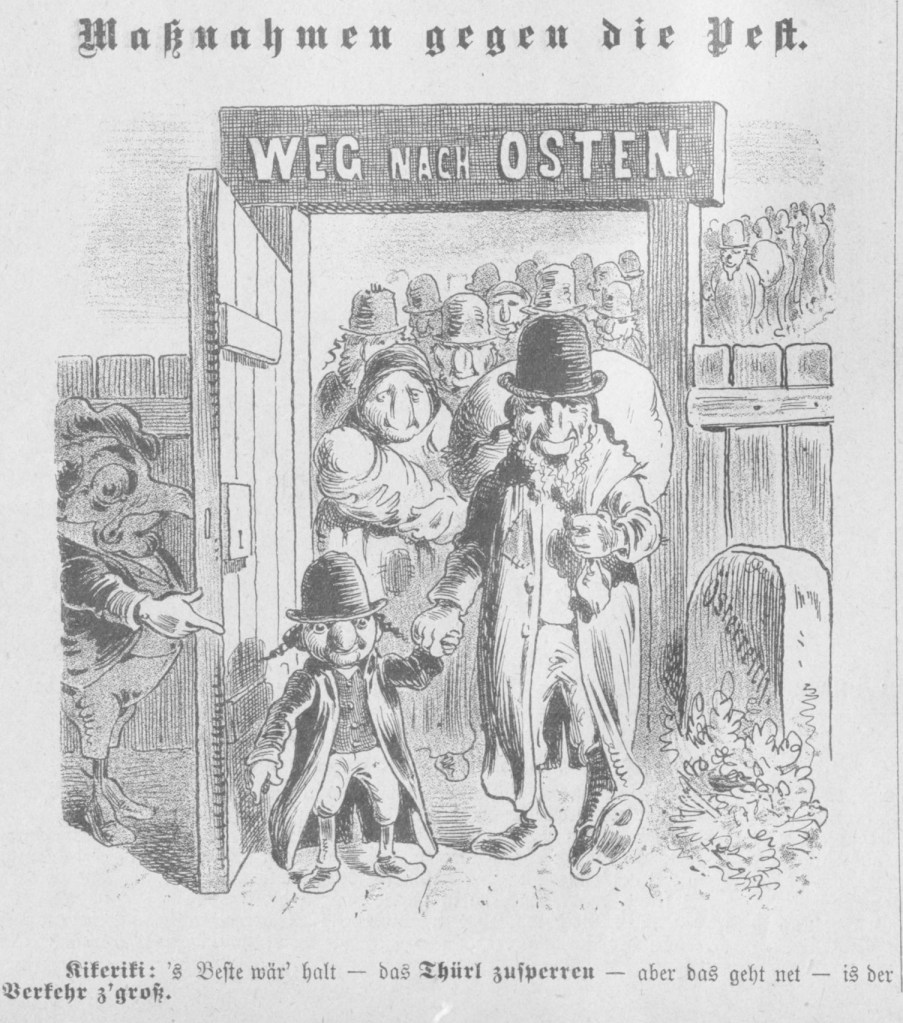

It may not feature much in this pandemic-themed archive, but it is worth pausing to acknowledge the relentless anti-Semitism of the Viennese satirical journal Kikeriki. In 1897 there was news of an outbreak of plague in India, sparking fears that it would make an appearance in Europe. The tenth international sanitary conference was held in Venice that same year, devoted to discussion of bubonic plague.

Entitled “Measures against the plague,” the cartoon depicts a gate into Austria with a sign above it: “The way to the East.”

Kikeriki: “The best thing would be to lock the doors, but that won’t do, the traffic is too large.”

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1897)

Another egregious example a decade later.

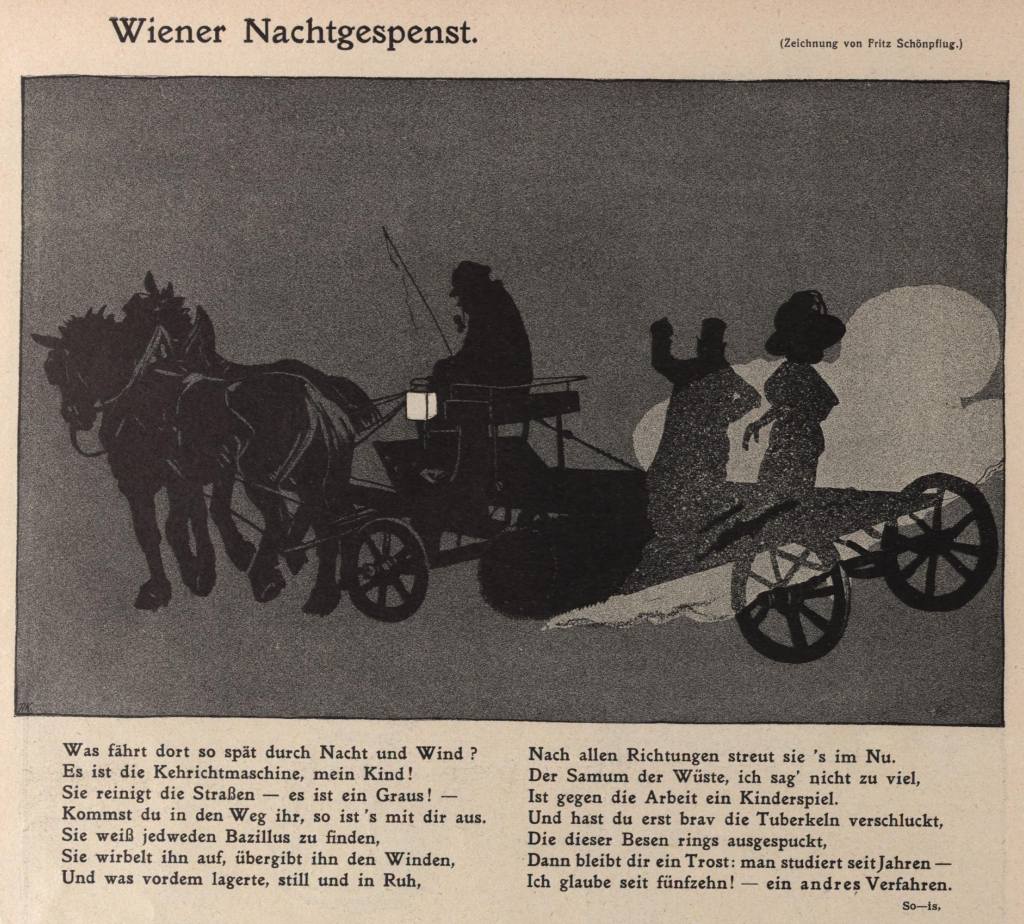

What drives through the wind so late at night?

It’s the street sweeper, my child!

It cleans the streets — it’s a horror! —

If you get in its way, you’re done for.

It knows how to find any germ,

It whirls it up, hands it over to the winds,

And what was lying around before, quietly at rest,

It scatters in all directions in no time.

The desert wind, I’m not overstating,

Is child’s play against this work.

And if you’ve just nicely swallowed the tubercles,

That these brooms spit out all around,

Then there is consolation: another process

is being studied — I think for fifteen years!

(Die Muskete, Vienna, 1912)

Tsar Nicholas II: “Haha! My little daughter understands sweeping up even better than my best governors…?!”

(Die Muskete, Vienna, 1908)

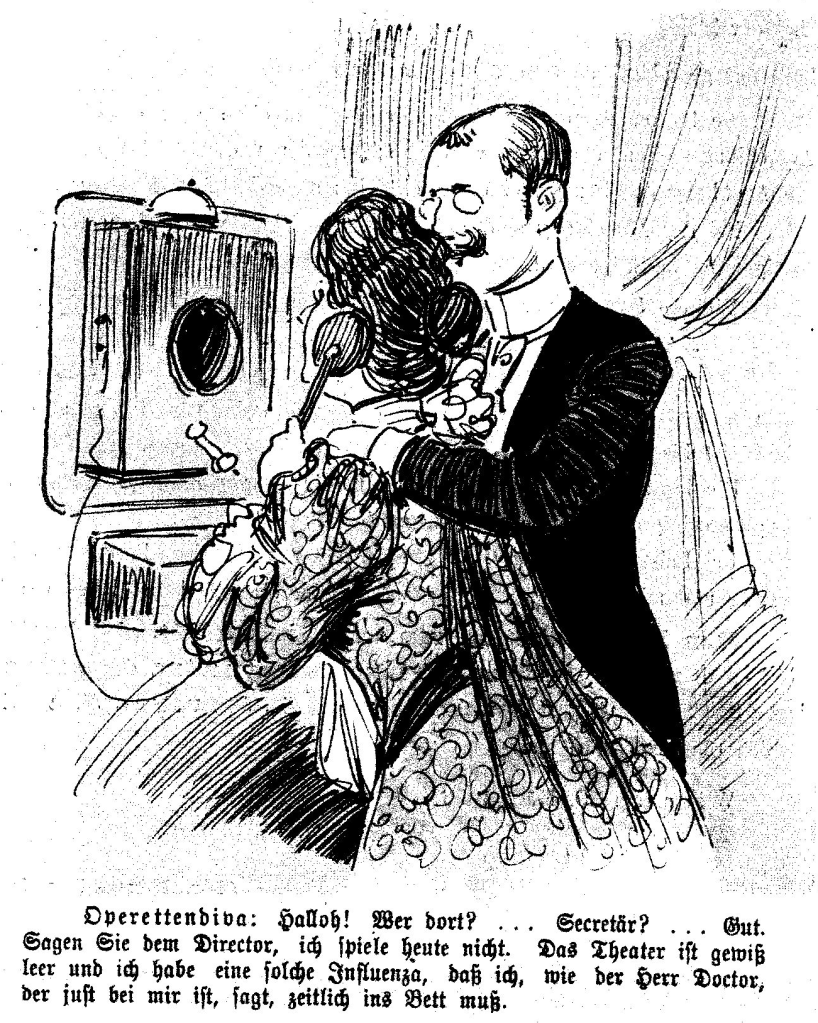

Opera diva: “Hello? Who’s there? … The secretary? … Good. Tell the director that I’m not performing tonight. The theater is definitely empty and I have such a case of flu that the doctor, who’s with me just now, says I have to take to bed for a while.”

(Der Floh, Vienna, 1899) (See a similar version, albeit with the diva invoking only generic illness, in the Russian magazine Oskolki in 1896.)

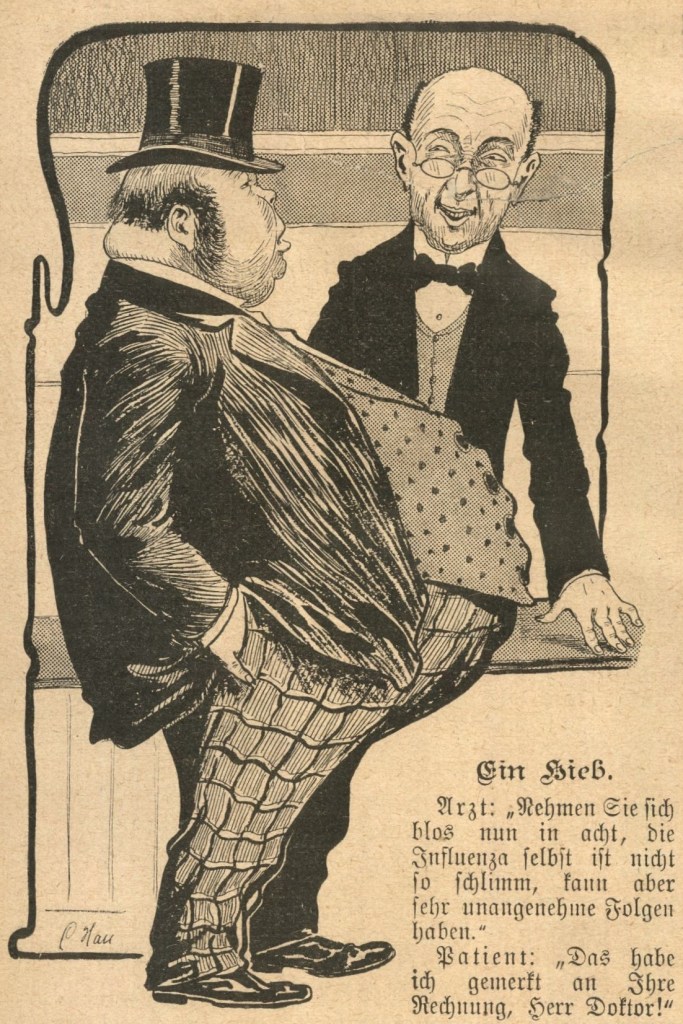

Physician: “Keep in mind that the influenza is itself not so bad, but it can have very unpleasant aftereffects.”

Patient: “I noticed that when I got your bill, Doctor!”

(Humor/Neues Wiener Journal, Vienna, 1900)

A nearly identical cartoon in Der Floh, Vienna, 1899:

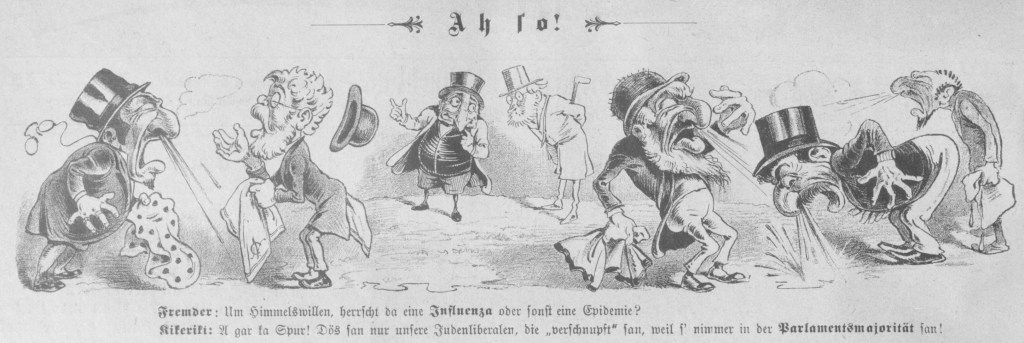

An uncomfortable reminder of the prevalent anti-Semitism in Vienna at the fin-de-siècle.

Stranger: “For heaven’s sake, does an influenza prevail there or some other kind of epidemic?”

Kikeriki: “Not a trace! This is only coming from our Jewish-Liberals, who are “sniffing” in irritation because they’re never in the parliamentary majority!”

(Kikeriki, Vienna, 1897)

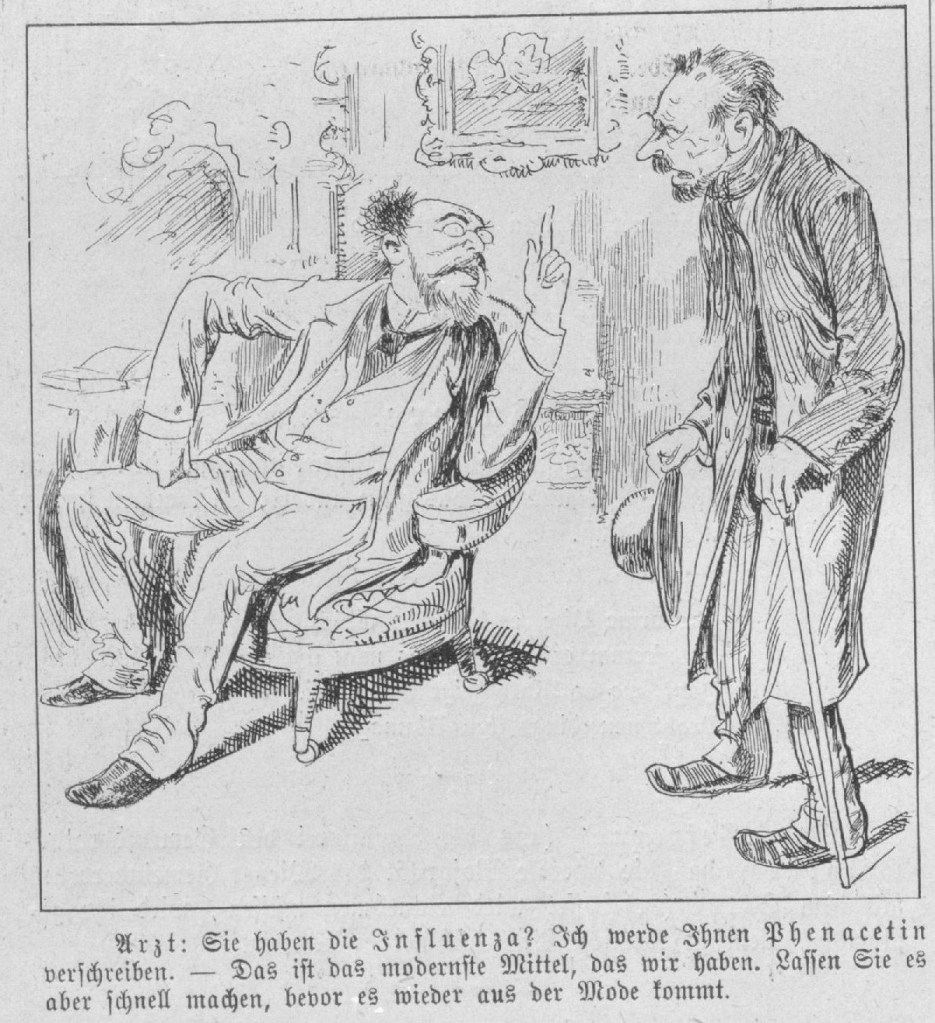

Doctor: “You have the flu? I’ll prescribe you Phenacetin. It the most modern treatment that we have. But do it quickly, before it goes out of fashion.”

(Figaro, Vienna, 1895)

The former Austrian foreign minister, Count Beust, had clashed with the French foreign minister, the Duc de Gramont, in the lead-up to the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. This cartoon from early 1873 followed upon Beust’s attempt to settle accounts by publishing letters from that period. Though this is straight politics, I include it because of the clystères, an ongoing theme. (See also this Mexican example from 1886, also a cholera year.)

(Humoristické listy, Prague, 1873)

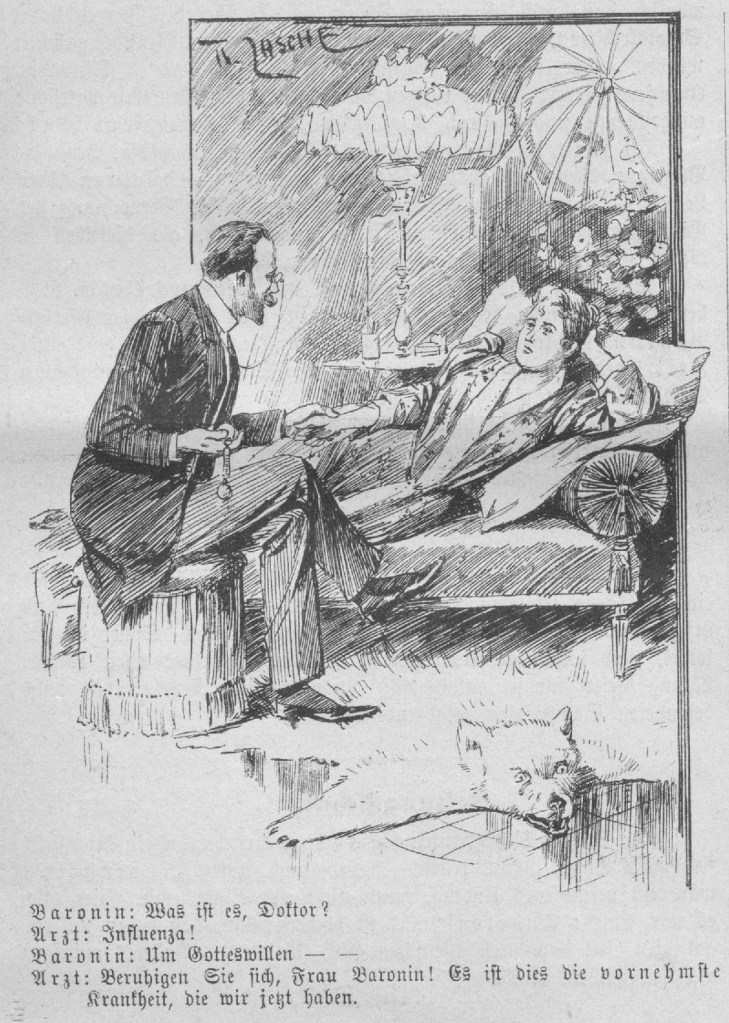

Baroness: “What is it, doctor?”

Doctor: “Influenza!”

Baroness: “Oh my goodness…”

Doctor: “Calm yourself, Madame Baroness! This is the noblest illness there is right now!”

(Figaro, Vienna, 1892)