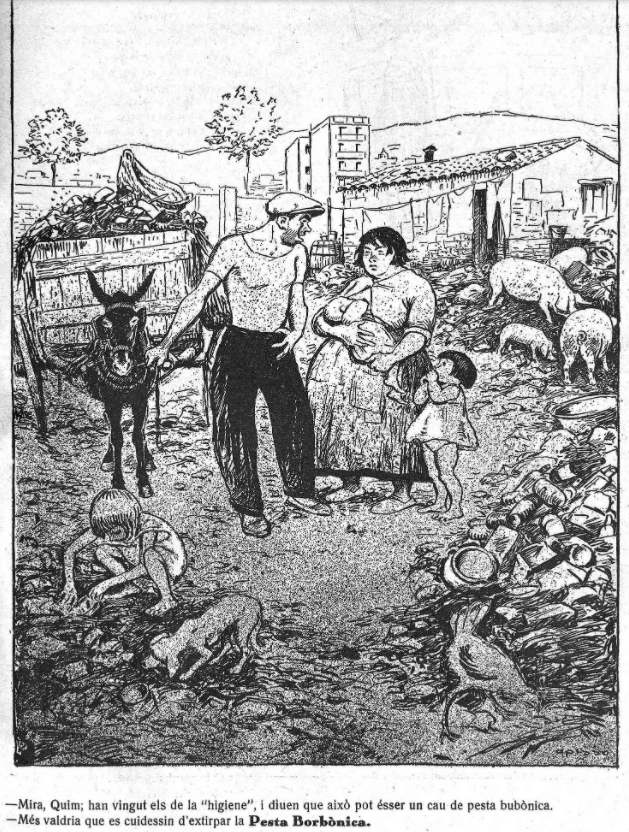

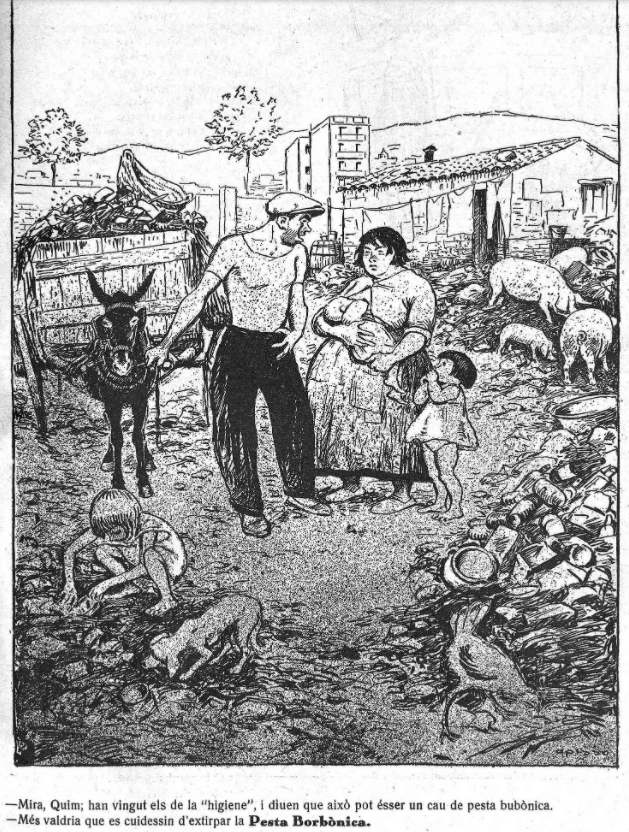

“Look, Quim; those “hygiene” people were here, and they say that this might be a den of bubonic plague.”

“It would be better to take care to eradicate the Bourbon Plague.”

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1931)

“Look, Quim; those “hygiene” people were here, and they say that this might be a den of bubonic plague.”

“It would be better to take care to eradicate the Bourbon Plague.”

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1931)

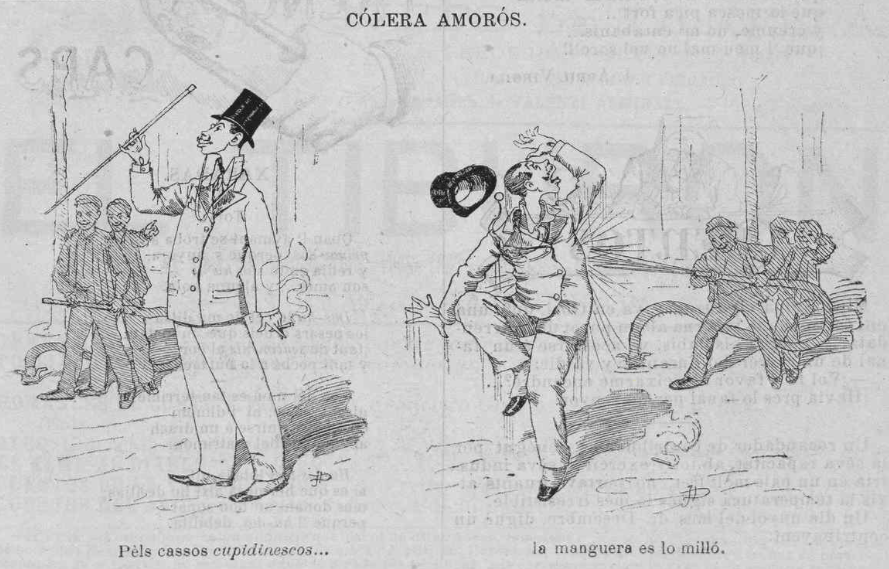

For the lover-boy cases… the hose is the best.

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1890)

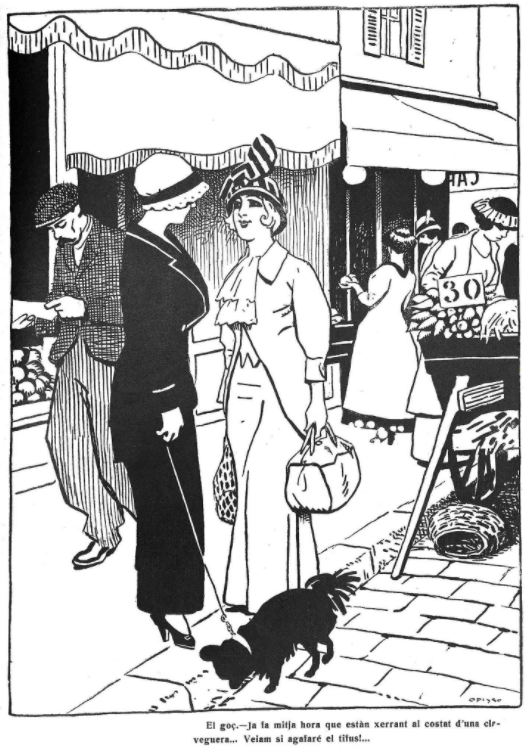

(Wife waiting for husband?) “It’s been half an hour since they’ve been chatting next to a beer garden… Let’s see if I can catch typhus!…”

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1914)

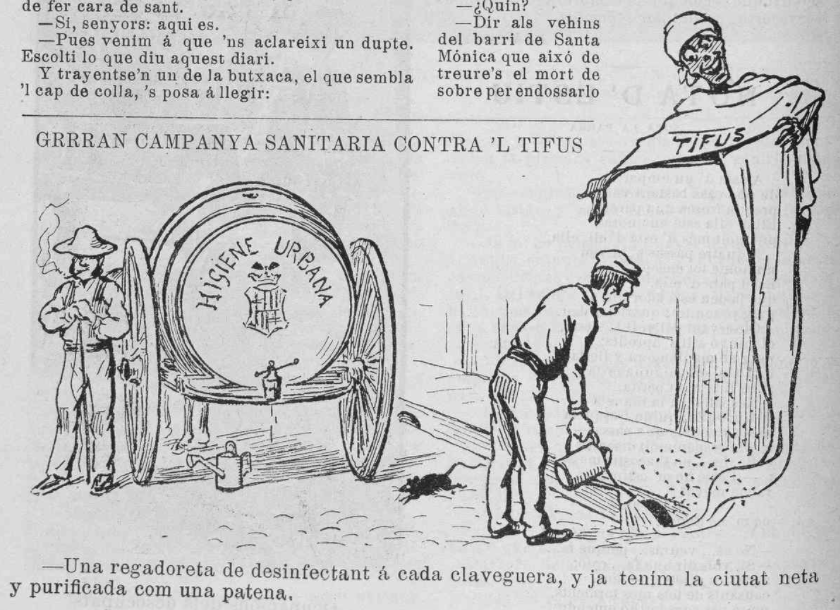

A sprinkling of disinfectant in each sewer, and we already have the city clean and purified like a dinner plate.

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1900)

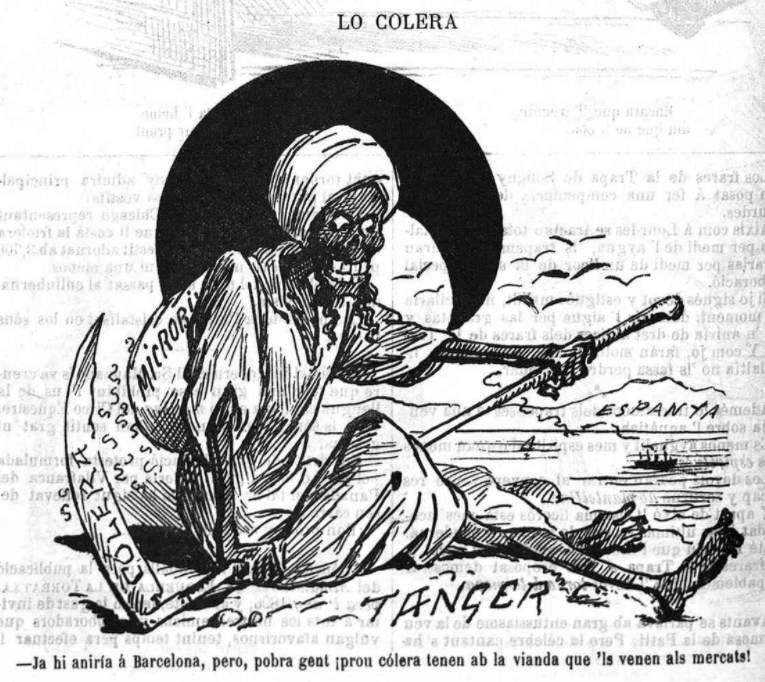

I would go to Barcelona, but, poor people, they have enough cholera with the food they sell in the markets!

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1895)

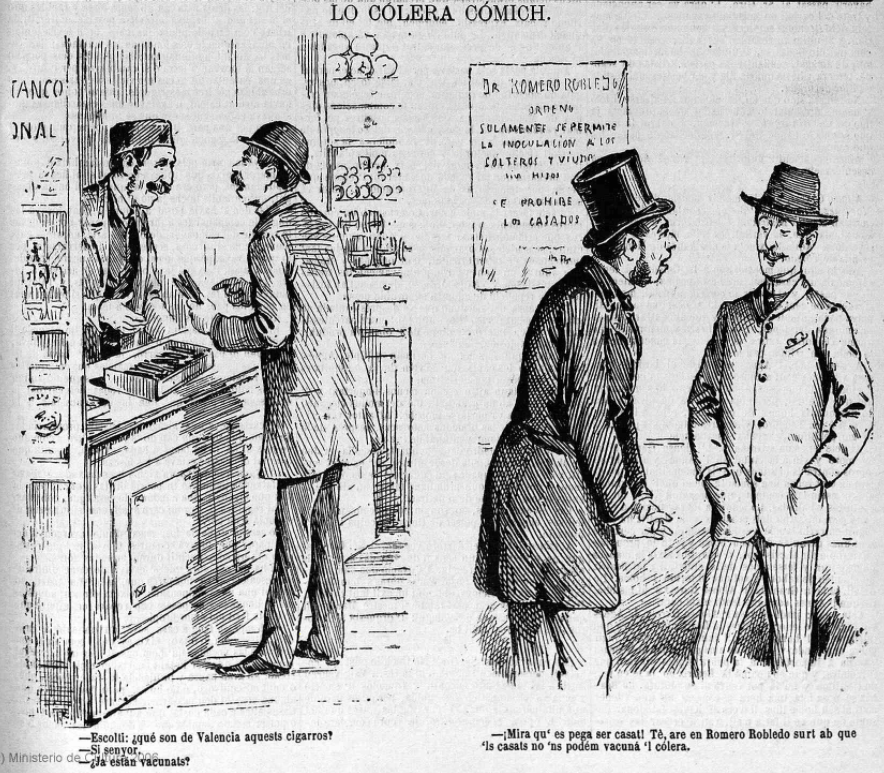

(left) “Listen, are these cigars from Valencia?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Are they already vaccinated?”

(right, where sign indicates that inoculation is only available to unmarried single men and widows: married people are forbidden): “Look what trouble it is to be married! You, has it come out in Romero Robledo [Spanish Interior Minister] that married men cannot vaccinate cholera.” [I’ve got this idiom wrong, but you get the idea…]

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1885)

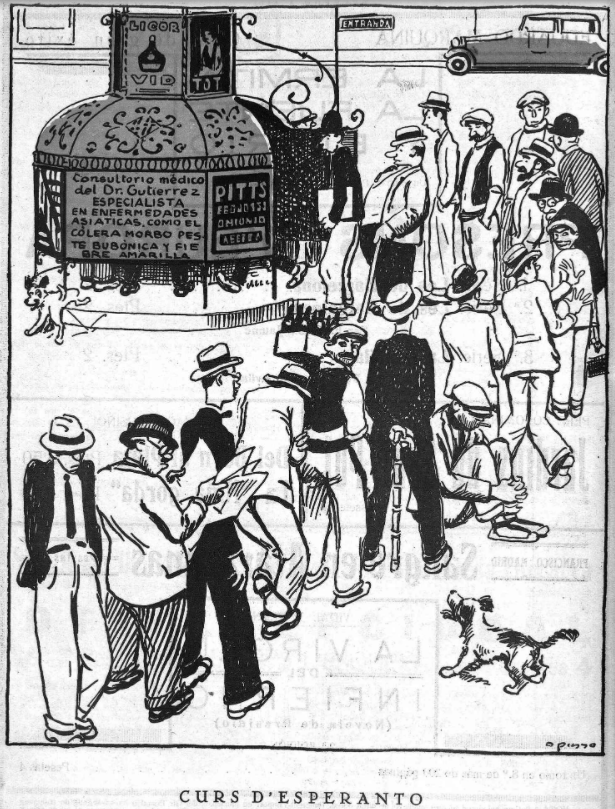

The all-purpose kiosk includes medical consultation with Dr. Gutierrez, specialist in Asiatic diseases like cholera, bubonic plagues, and yellow fever.

(La Esquella de torratxa, Barcelona, 1927)

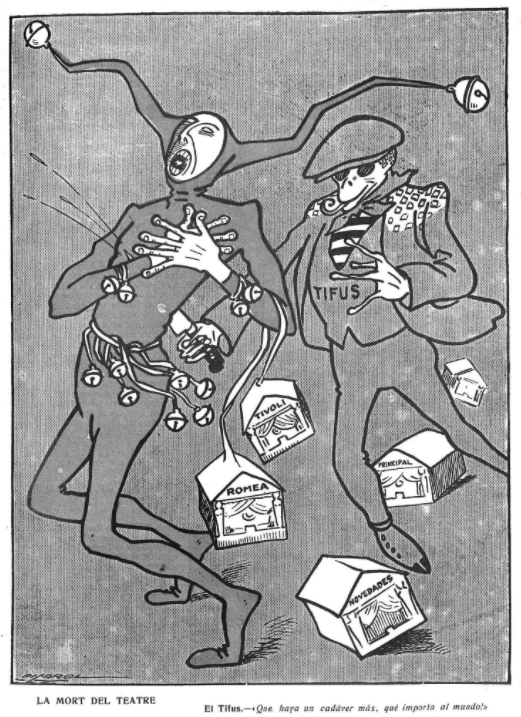

Typhus: “What does one more corpse matter to the world!” (Major theaters closed as typhus knifes a harlequin in the back.)

(La Esquella de torratxa, Barcelona, 1914)

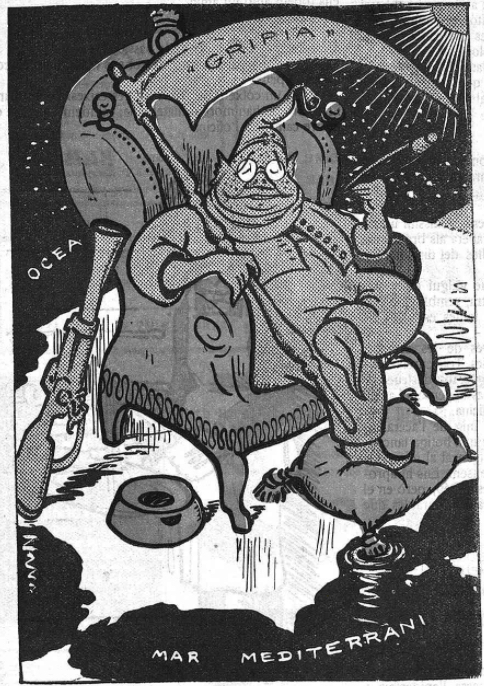

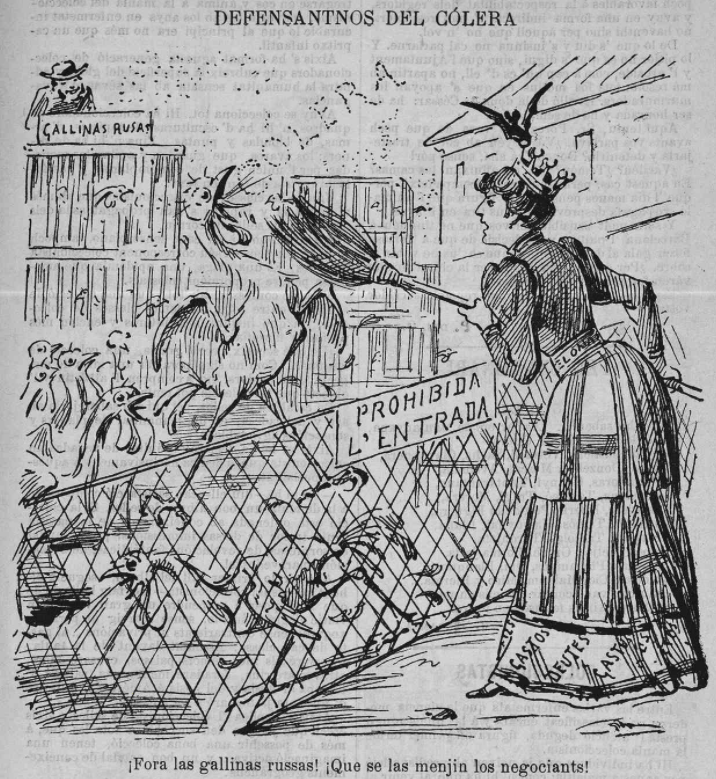

The Spanish monarchy guarding the “No entry” gate. “Out with the Russian chickens! Let the merchants handle them!”

(I’m ignorant of the politics, but the dress has “debt expenses” stenciled on it, and we may presume that the state minimizing its role in fighting the cholera epidemic is being derided here.)

(La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 1892)

“Come on, handsome, censor me!” (La Esquella de la torratxa, Barcelona, 27 September 1918)

Because wartime censorship was less strict in Spain, more newspapers reported on the rising epidemic of influenza in 1918, and much of the rest of Europe thus came to refer to it misleadingly as the “Spanish flu.” But in Spain itself the occasional Orientalism remained useful in depicting the origin of the disease. (La Esquella de la tarratxa, Barcelona, 11 October 1918)