“What is the meaning of this costume?”

“Mr. Director, my wife has the flu, I’ve come to replace her.”

(Le Journal amusant, Paris, 1907)

“What is the meaning of this costume?”

“Mr. Director, my wife has the flu, I’ve come to replace her.”

(Le Journal amusant, Paris, 1907)

From a 72-panel review of the first trimester of 1858 by Nadar.

(Le Journal amusant, Paris, 1858)

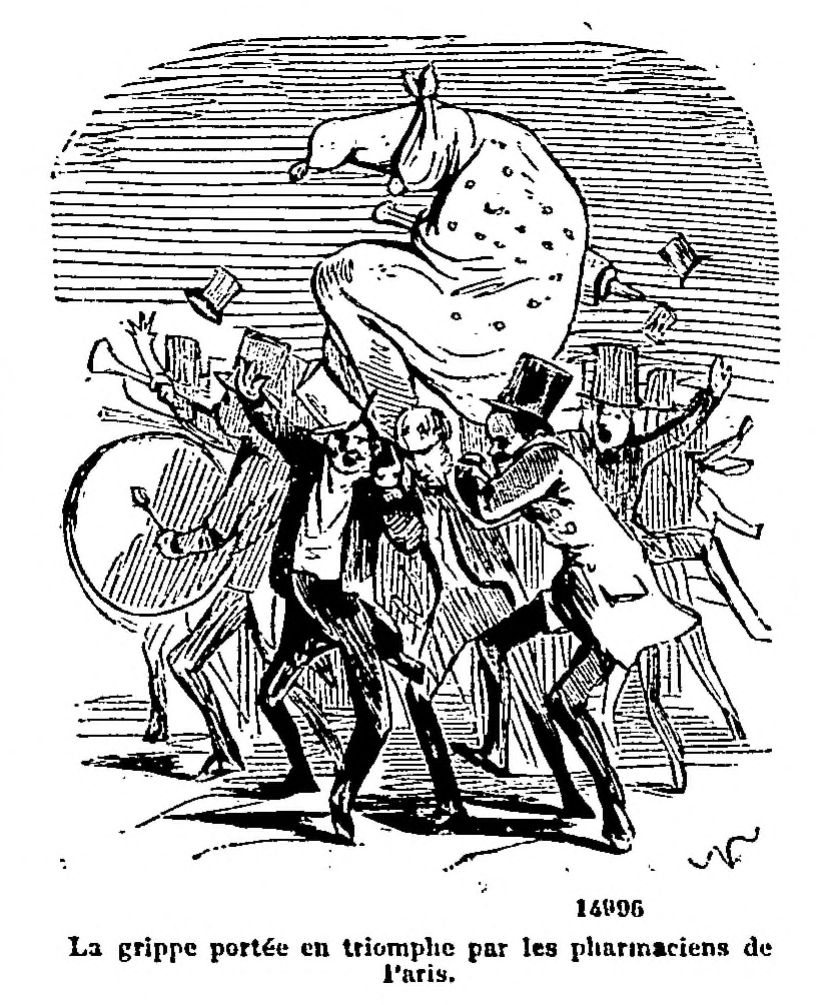

The flu born in triumph by the pharmacists of Paris.

Please pardon me for appearing in this state; but I have the flu!…

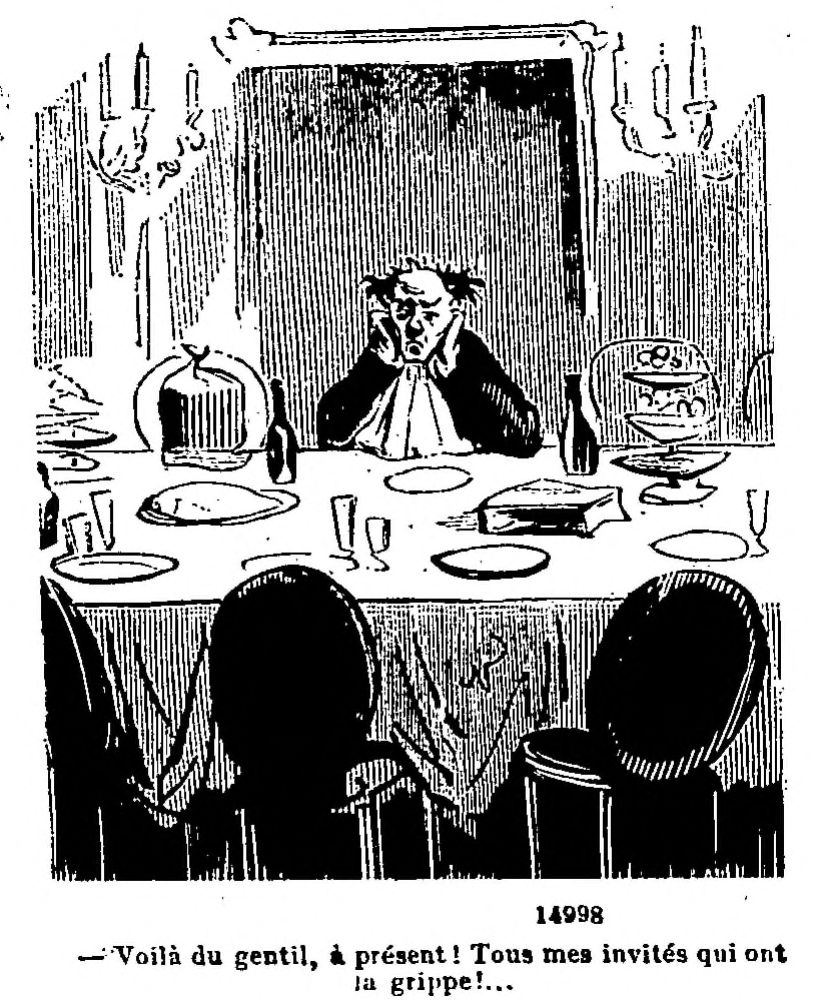

That’s nice now! All the people I invited have the flu!…

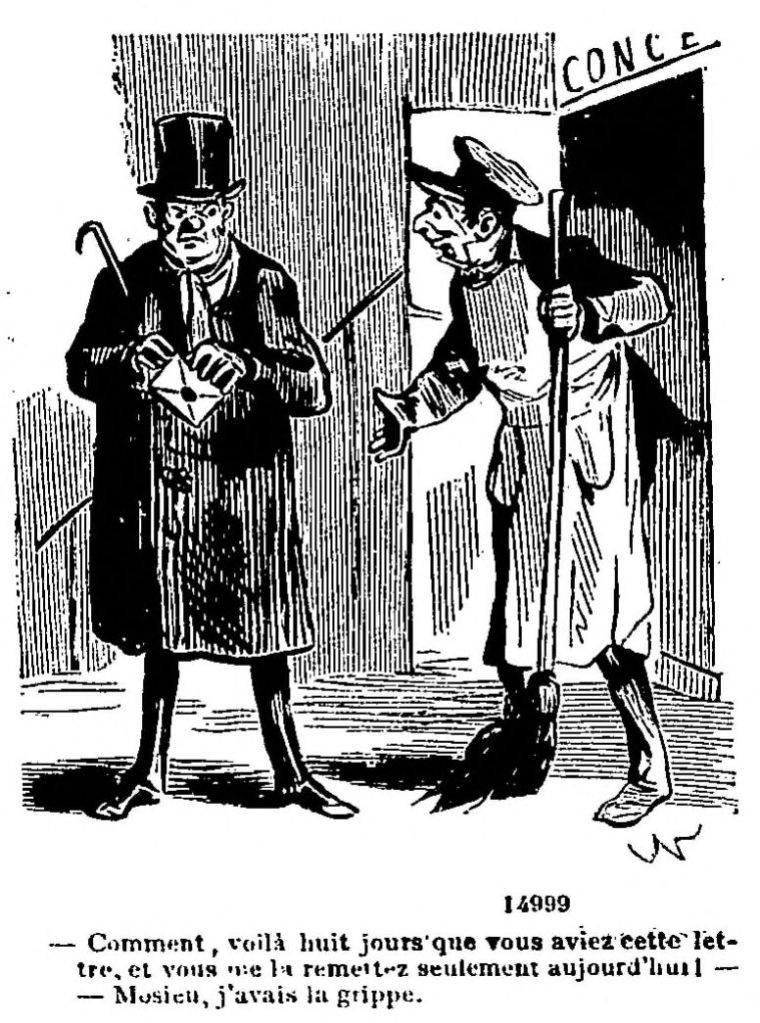

“How is it you’ve have this letter for eight days, and you are only giving it to me today!”

“Mister, I had the flu.”

“Do you have any idea about this fool of a doctor who found a temperature curve in me!”

(Le Rire, Paris, 1919) (I doubt this idiom is adequate to the bad pun. The poor cubist has lost his edge, so to speak.)

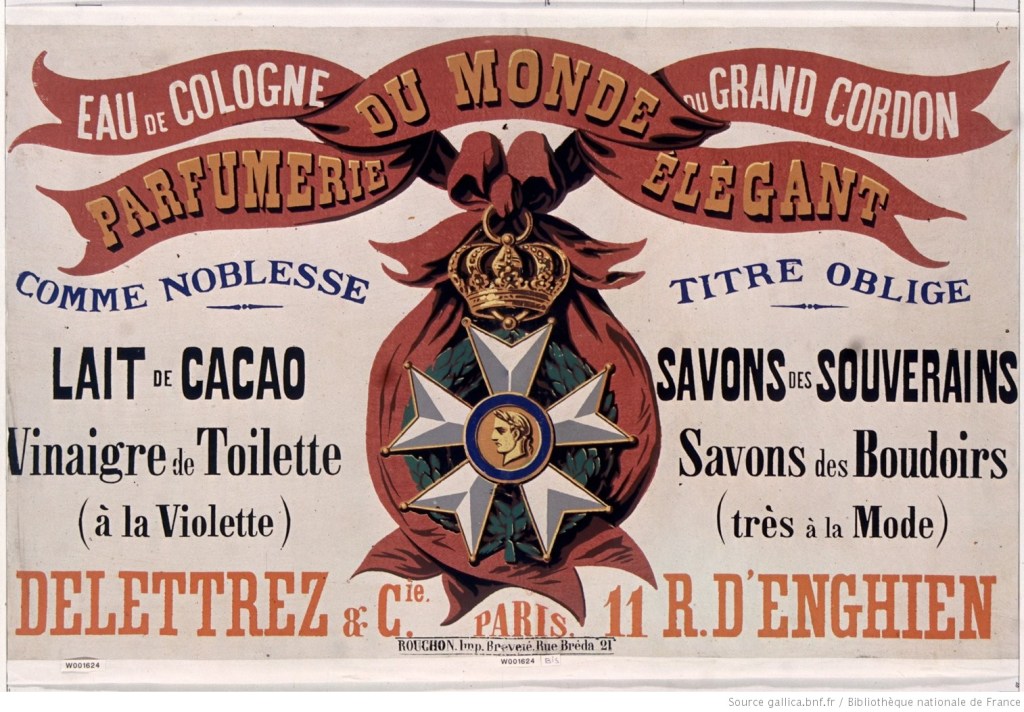

Though we are archiving visual epidemic humor, a brief gesture toward the sense of smell seems appropriate. The Parisian parfumerie Delettrez began selling L’eau de cologne du Grand-Cordon in 1857, and this unisex perfume seems to have established the Delettrez brand. Less expected (at least for me) was its embrace by the Parisian public as one of the many elixirs against cholera. Although Pasteur’s germ theory was beginning to make headway at the time of the 1884 epidemic resurgence, miasmatic theories still predominated in the general public.

Consider this endorsement from Le Voleur illustré: “We could not recommend too much to our readers of both sexes the use of l’eau de cologne du Grand-Cordon, which is not only a first-rate perfume and cosmetic, but also a very effective product against the miasmas and unhealthy fumes so dangerous in times of cholera. It is wise to use l’eau de cologne du Grand-Cordon every morning, to soak your handkerchief and linen with it, and to carry a bottle with you. Such precautions, even if exaggerated, never hurt anyone.”

A different sense of “cordon sanitaire“?

Gabriel Liquier penned cartoons under the aliases Trick and Trock for La Caricature in Paris. Around the time that cholera was peaking again in France in 1884, some of his miscellaneous drawings touched on the epidemic, and we shall collect them together here. (As usual, links to sources are embedded in the images.)

“Where are you going so quickly, Calino?”

“I am taking precautions against cholera: I’m off to buy a cordon sanitaire.”

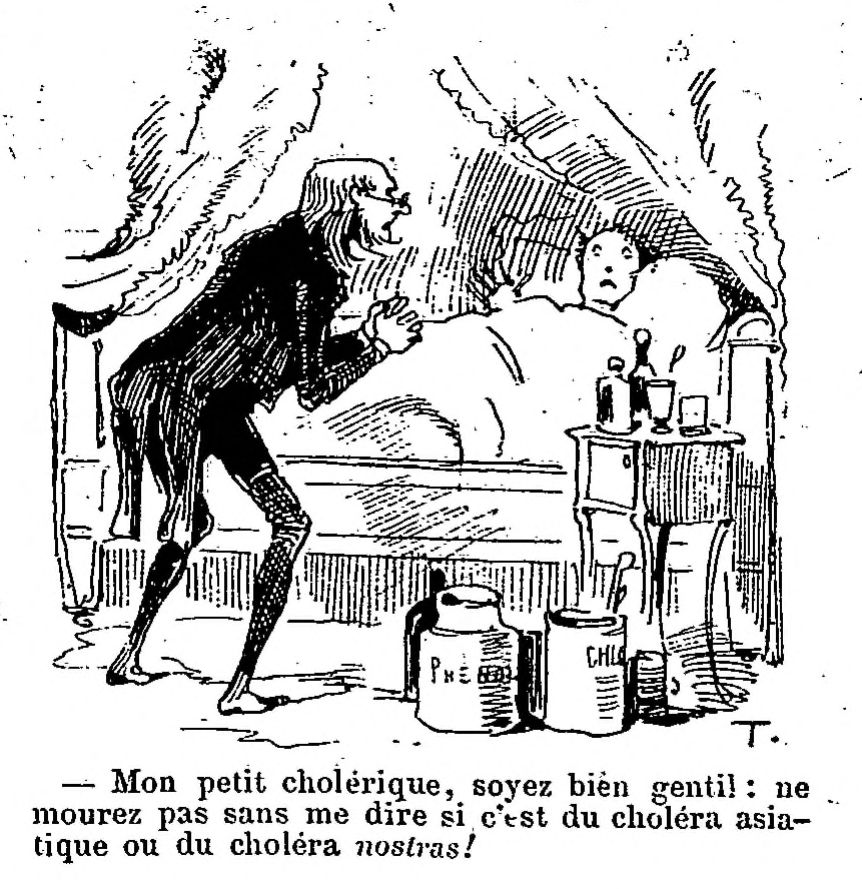

“My little choleric, be very nice: don’t die without telling me if it’s Asian cholera or our cholera!”

“Are you suffering from sciatica? Oh, my poor sir, that is a symptom of cholera…”

“Not possible!”

“It’s a sciatic cholera.” (“Asiatic”)

(The same pun was recycled in 1892 in Le Journal amusant.)

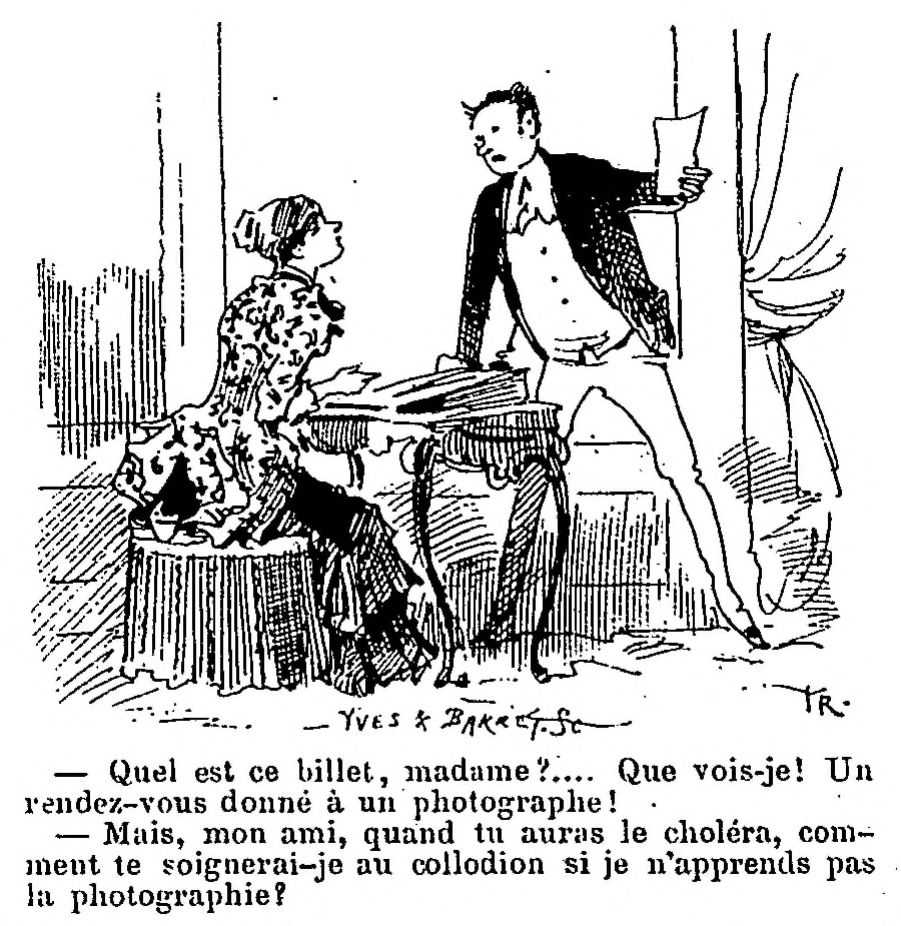

“What is this note, madame?… What am I looking at! An appointment granted to a photographer!”

“But, my love, when you have cholera, how will I cure you with collodion if I don’t learn photography?”

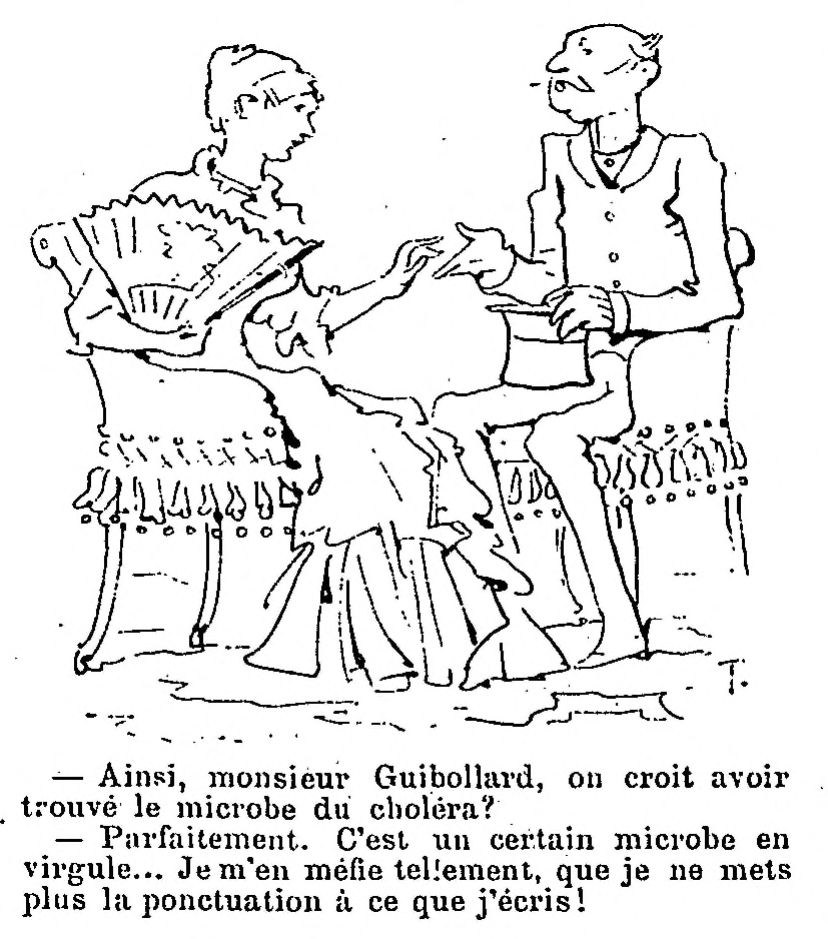

“So, Mr. Guibollard, do they think the cholera microbe has been found?”

“Perfectly. It’s a certain comma microbe… I’m so sure of it that I no longer put punctuation in what I write!”

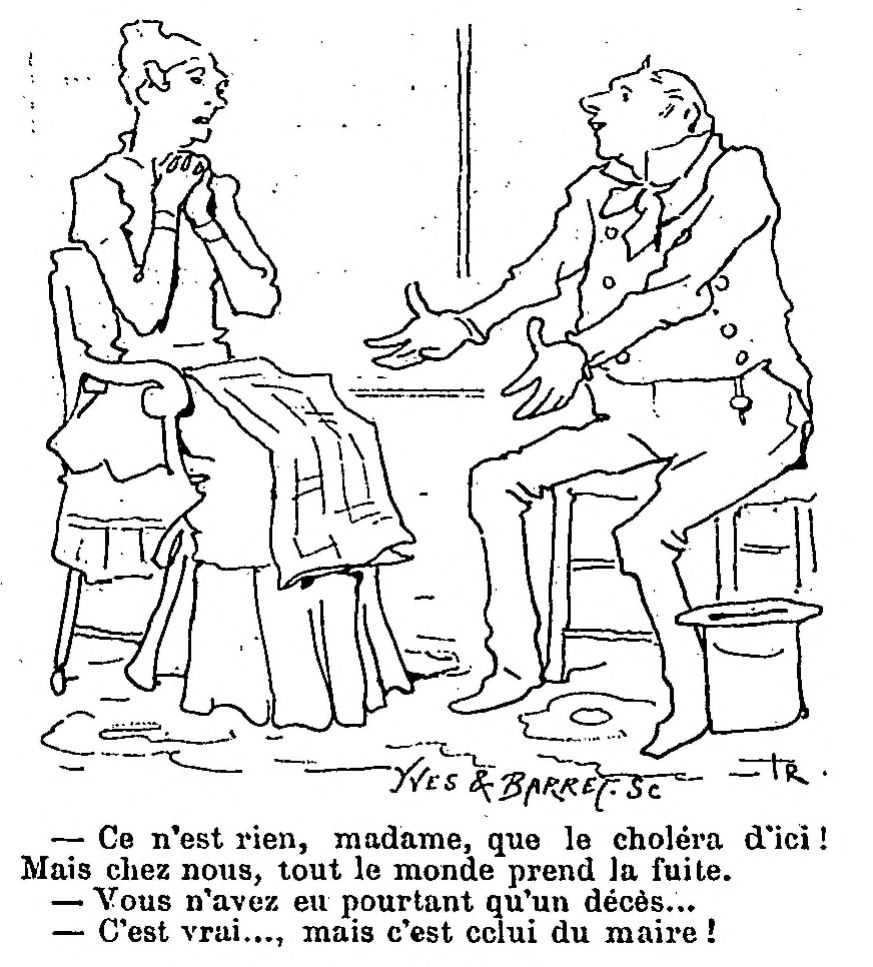

“The cholera from here is nothing, madame! But with us, everyone flees.”

“Yet you have only had one death…”

“That is true…, but it is that of the mayor!”

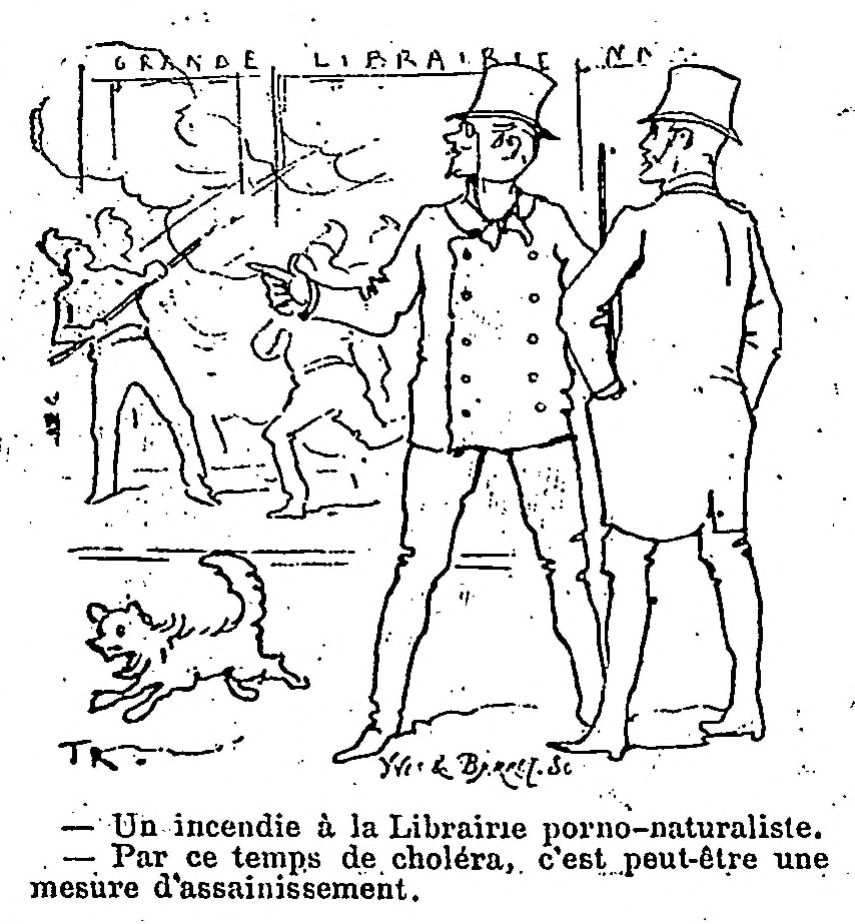

“A fire at the Porno-Naturalist Library.”

“In this time of cholera, it may be a sanitation measure.”

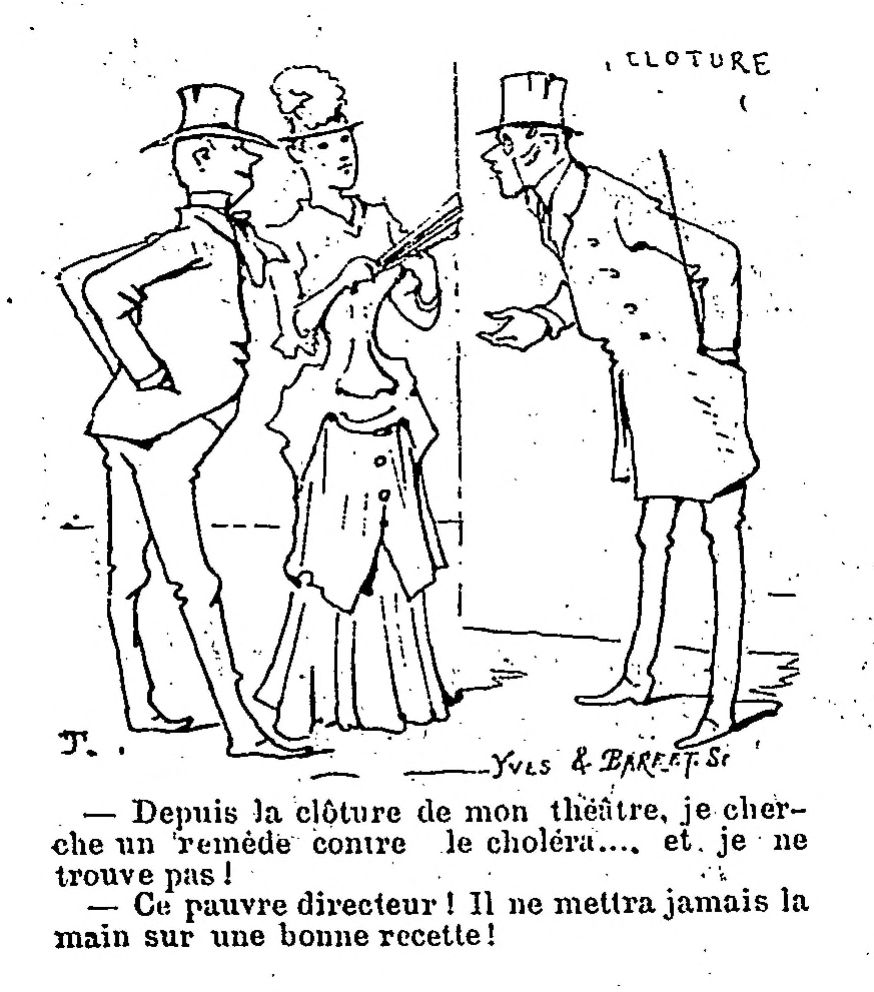

“Since the closing of my theater I have been looking for a remedy against cholera…. and I haven’t found it!”

“This poor director! He will never get his hands on a good formula!”

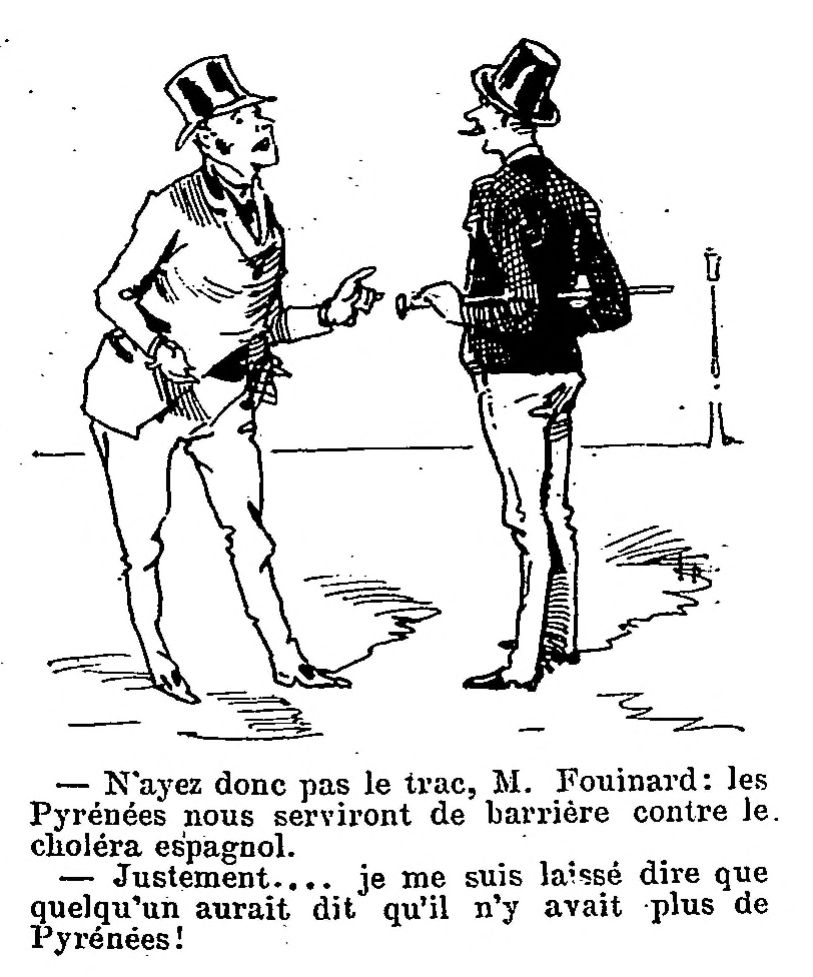

“So don’t be nervous, Mr. Fouinard: the Pyrenees will serve as a barrier against Spanish cholera.”

“Precisely… I let myself be told that someone would have said that there were no more Pyrenees!”

From La Caricature (1890):

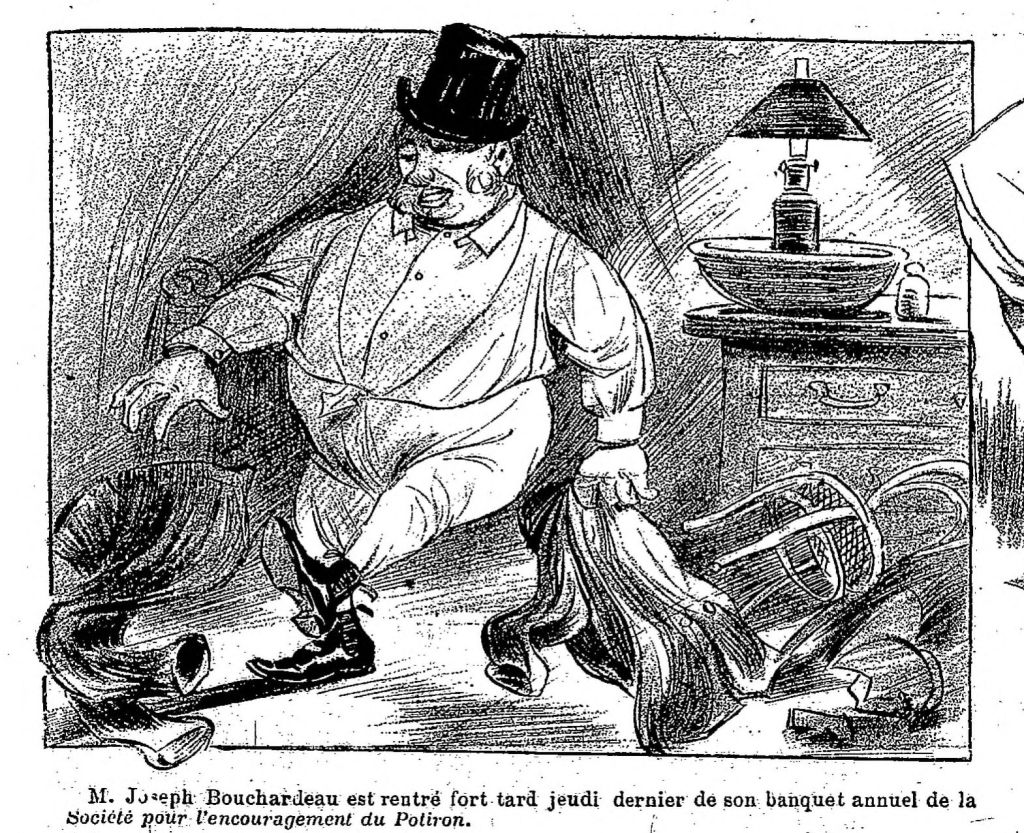

Mr. Joseph Bouchardeau returned very late last Thursday from his annual banquet at the Society for the Encouragement of the Pumpkin.

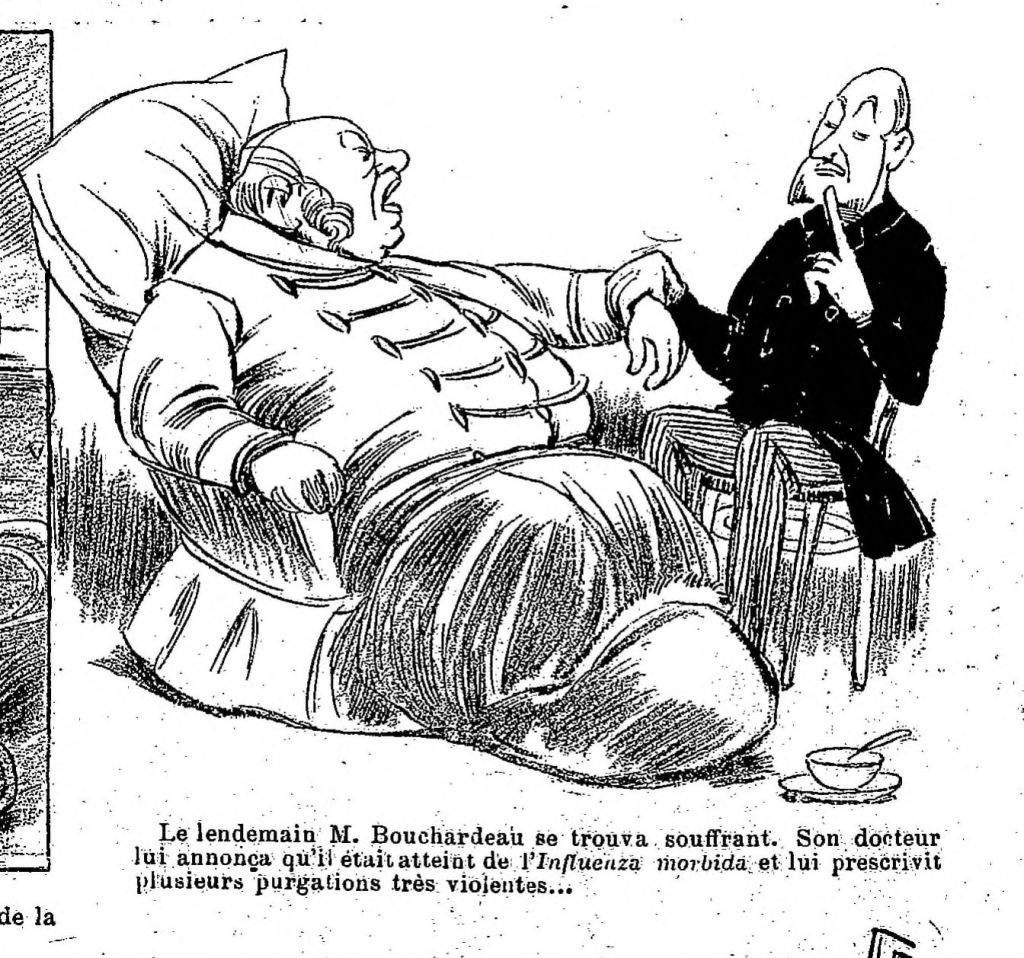

The next day Mr. Bouchardeau found himself ill. His doctor told him that he had morbid influenza and prescribed several very violent purgations…

These gave him the opportunity to get plenty of exercise, but the influenza persisted.

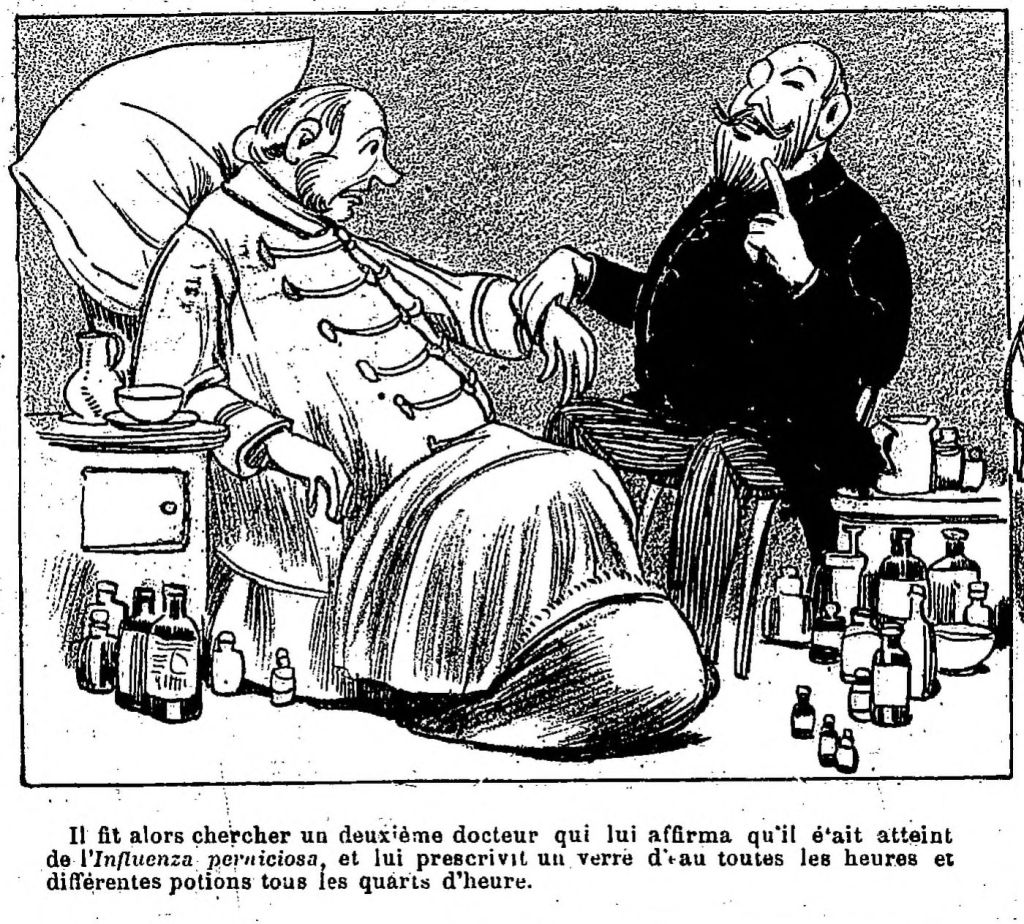

He then sent for a second doctor who told him that he had pernicious influenza and prescribed him a glass of water every hour and different potions every quarter of an hour.

Mr. Bouchardeau noted with sadness that he was visibly declining and that the pernicious influenza persisted anyway.

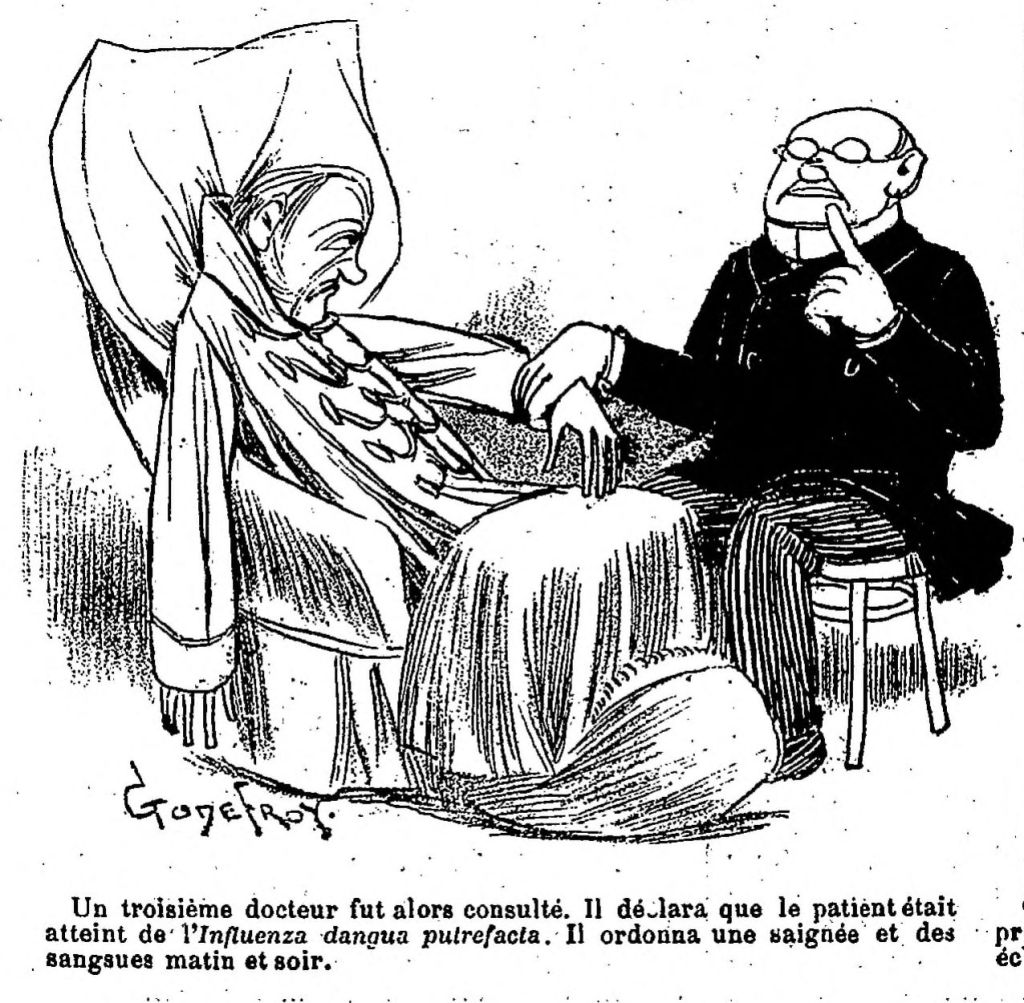

A third doctor was then consulted. He declared that the patient had influenza dangua putrefacta. He ordered bleeding and leeches morning and evening.

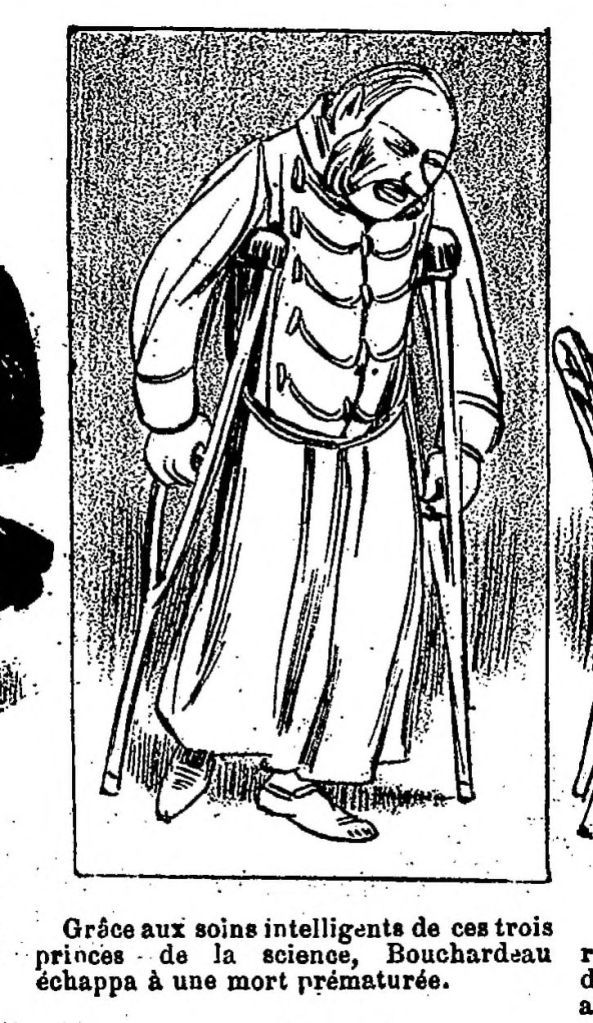

Thanks to the intelligent care of these three princes of science, Bouchardeau escaped a premature death.

So it was with a feeling of deep gratitude that he paid the bills of doctors, pharmacists, herbalists, etc., who had contributed to his salvation. However, he reflected that the annual pumpkin dinner was costing him a bit dearly, and he resolved to abstain from it henceforth.

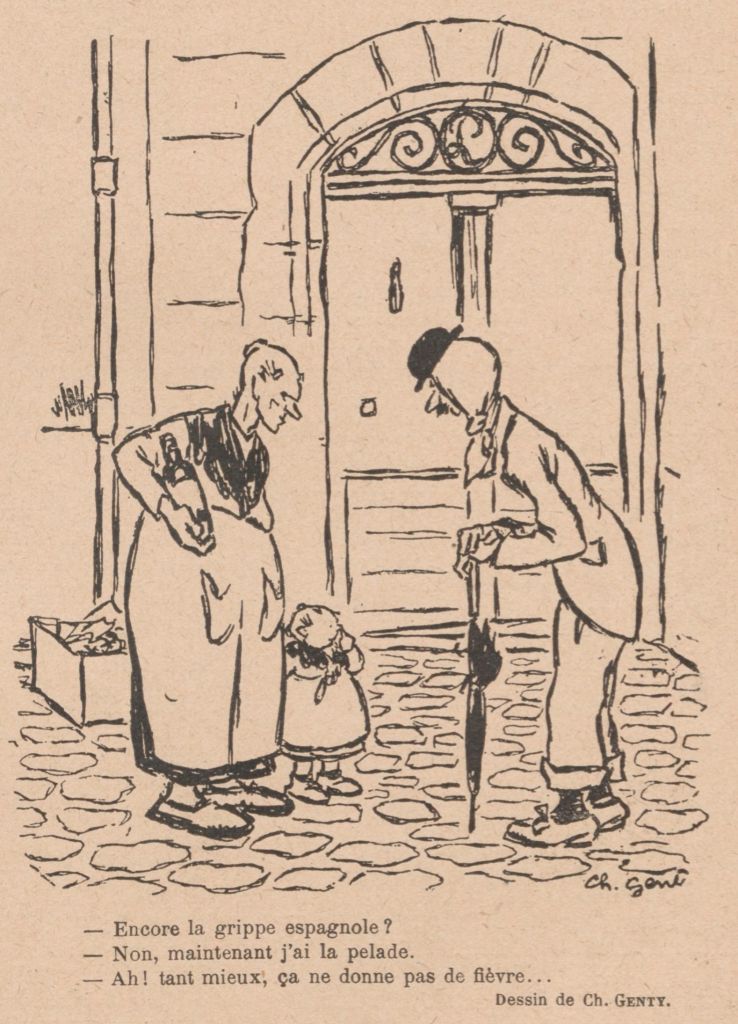

“The Spanish flu again?”

“No, now I have alopecia.”

“Ah! so much the better, it won’t give you fever…”

(Le Rire, Paris, 1918)

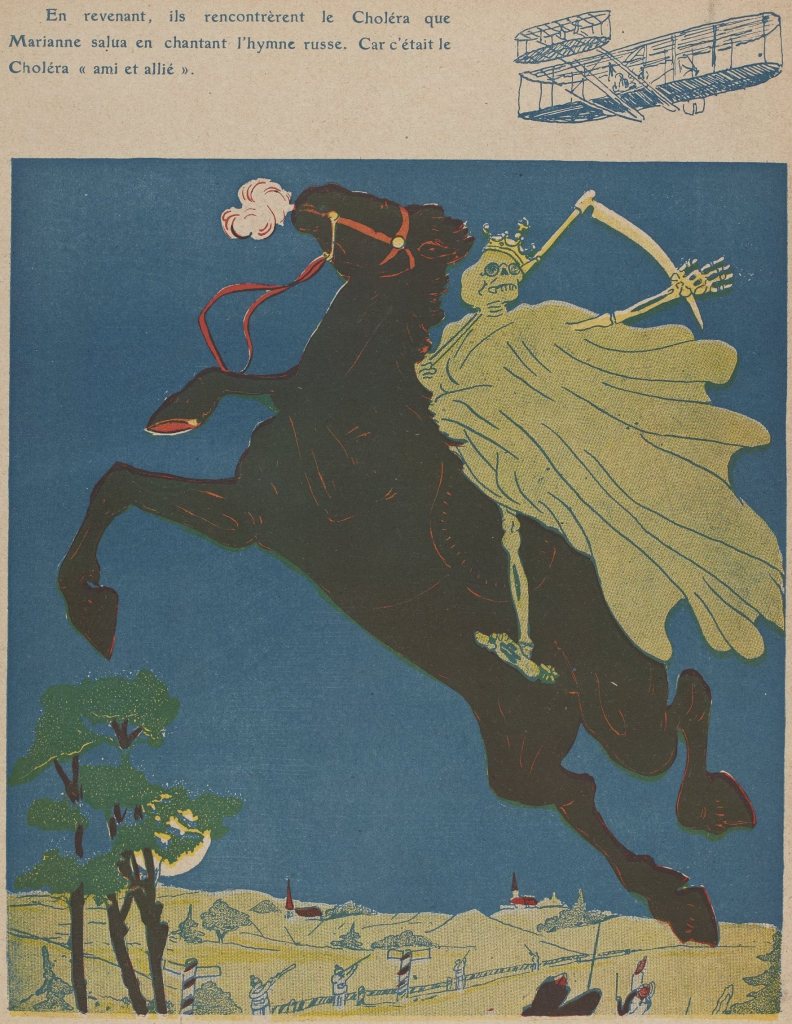

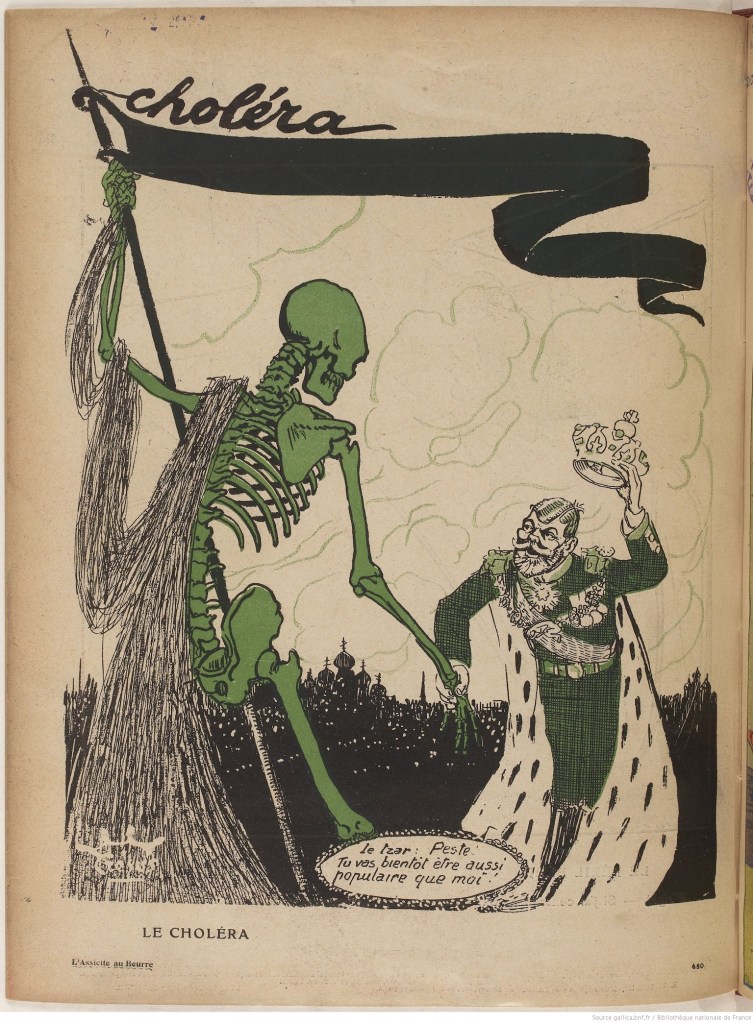

On the way back, they met Cholera whom Marianne [France] greeted by singing the Russian hymn. Because it was the “friend and ally” Cholera.

(L’Assiette au beurre, Paris, 1909) (Drawn at a time of close Franco-Russian diplomatic and military relations, in the midst of the last European cholera pandemic.)

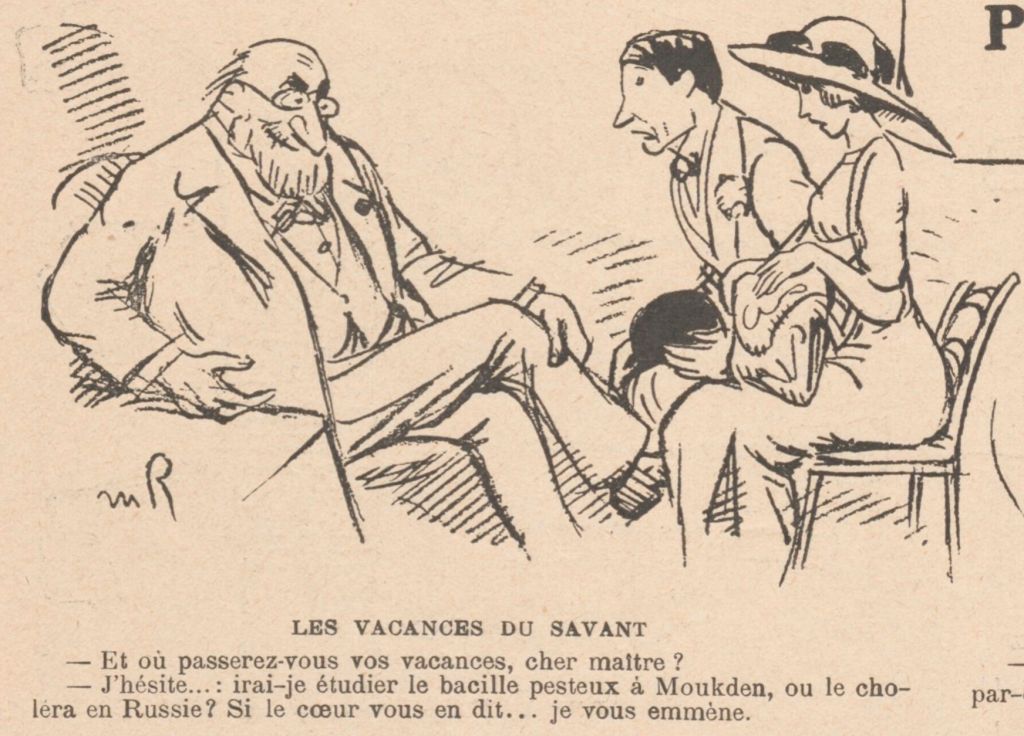

“And where will you spend your holidays, dear master?”

“I hesitate…: will I study the plague bacillus in Moukden, or cholera in Russia? If you feel like it… I’ll bring you along.”

(Le Rire, Paris, 1911)

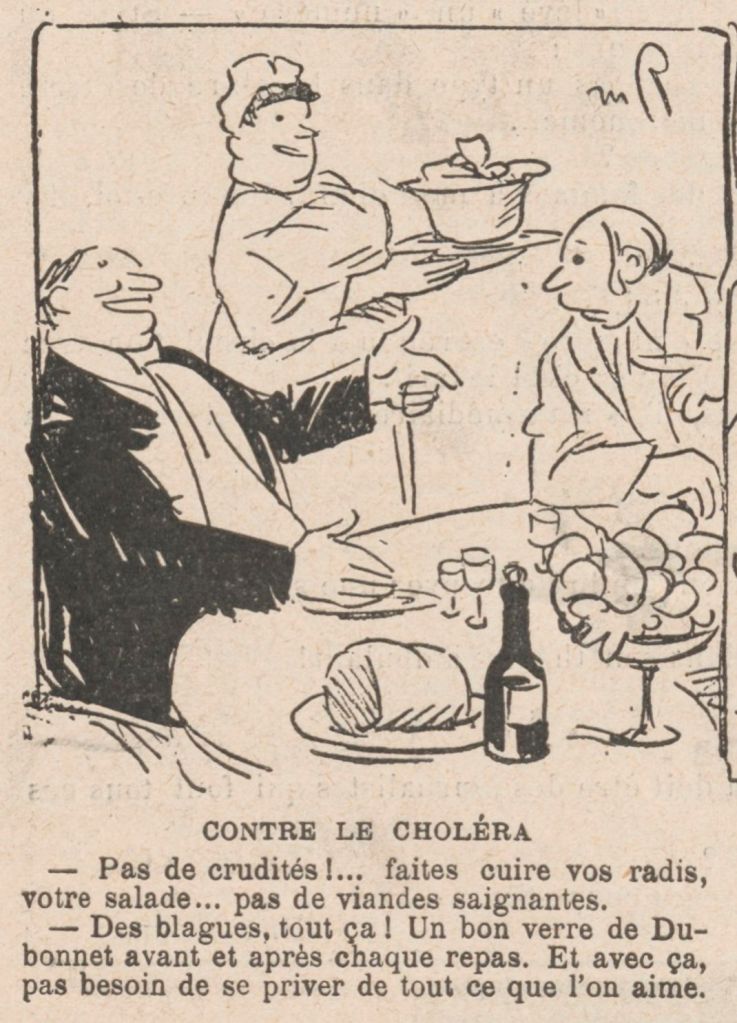

“No raw vegetables!… cook your radishes, your salad… no raw meats.”

“It’s all a joke! A good glass of [quinine-fortified] Dubonnet before and after every meal. And with that, no need to deprive yourself of everything you love.”

(Le Rire, Paris, 1911)

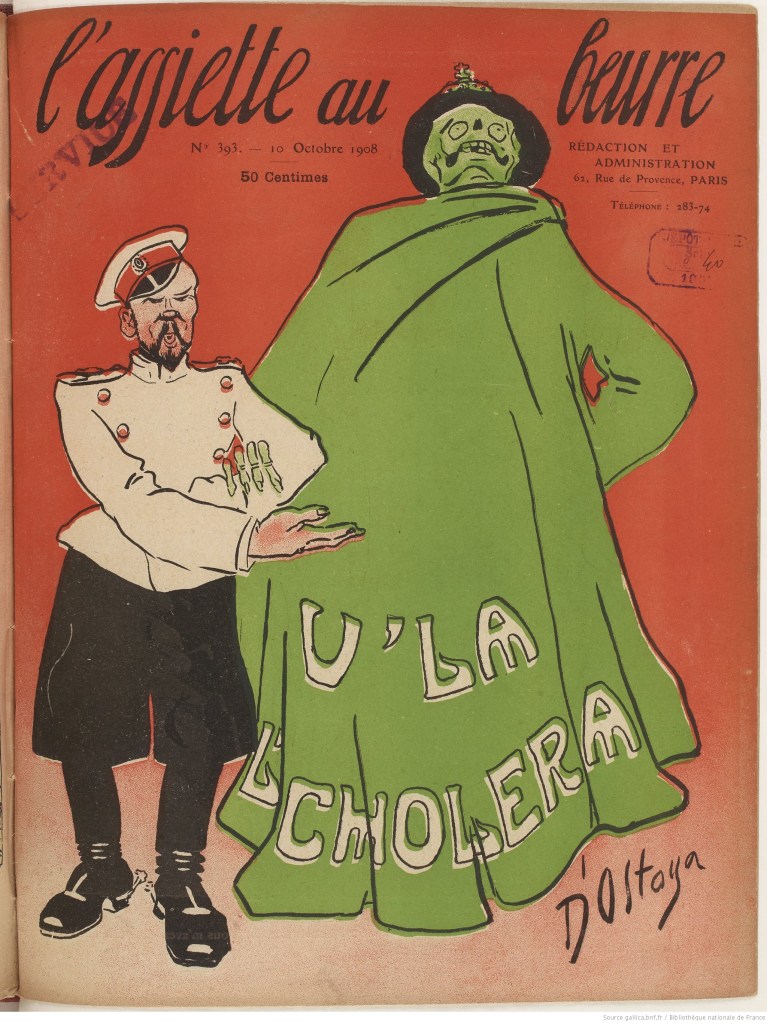

Since cholera spread from the Russian Empire further west in Europe in 1908, casting Tsar Nicholas II as the “host” was a popular gambit.

(L’Assiette au beurre, Paris, 1908)

Similarly a week later:

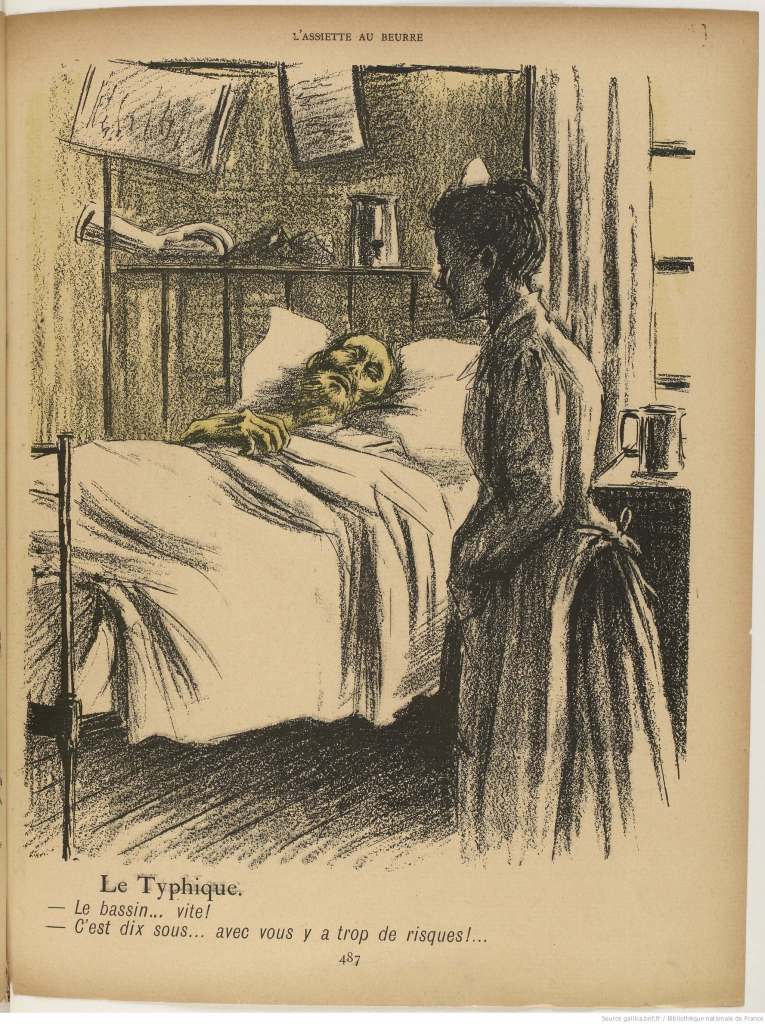

“The basin… quickly!”

“It costs ten sous… with you there are too many risks!…”

(L’Assiette au beurre, Paris, 1901)

“Ah! There you are, my husband!… What do you bring me from Africa, my darling?”

“I’m bringing you a dysentery and an ophthalmia…”

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1849)

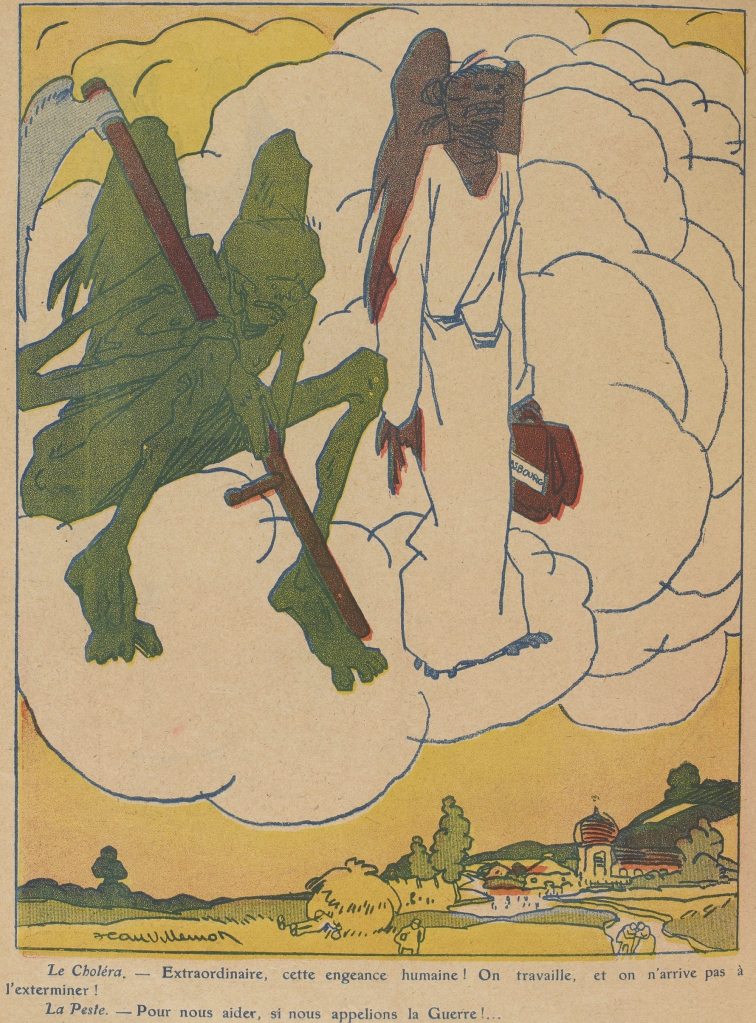

Cholera: “Extraordinary, this human breed! We work, and we can’t exterminate it!”

Plague: “Would it help us if we summoned War?”

(L’Assiette au beurre, Paris, 1908)

(Bicycle agents directly fill prescriptions by service pharmacists.)

“Do not worry… In the police, we know the ‘prescriptions’!”

(Excelsior, Paris, 1918)