Military infirmary attendant during the exercise of his functions. (From the ongoing clystère theme.)

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1845)

Military infirmary attendant during the exercise of his functions. (From the ongoing clystère theme.)

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1845)

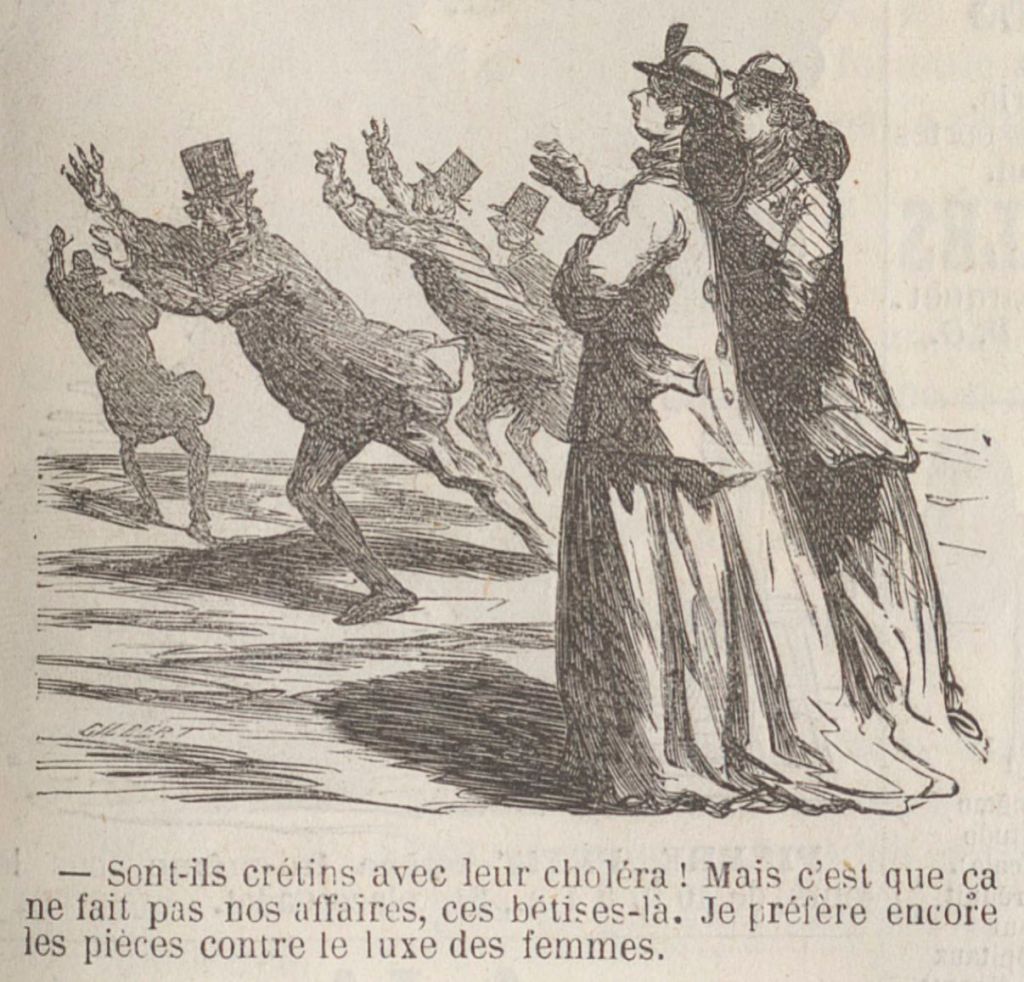

“What fools they are with their cholera! But it’s none of our business, this nonsense. I still prefer newspaper pieces against women’s luxury.”

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1865)

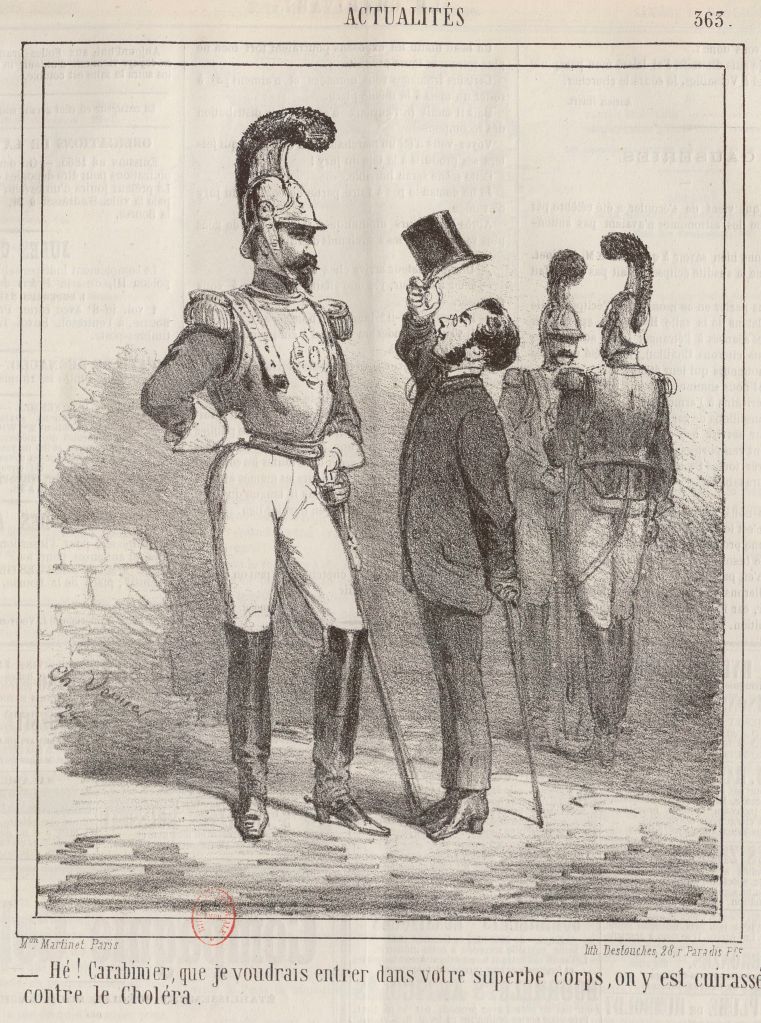

“Hey! Rifleman, I’d like to join your superb corps, everybody there is armored against the Cholera.”

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1865)

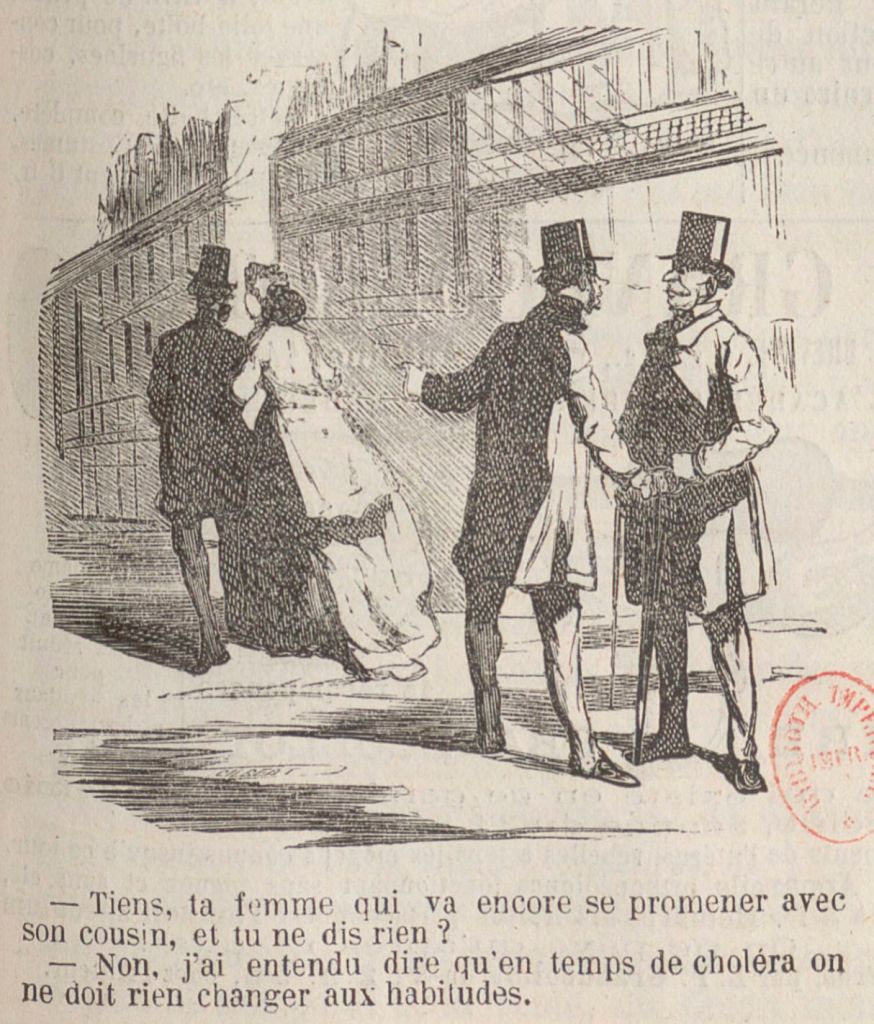

“Hallo, isn’t that your wife going for a walk with her cousin again, and you say nothing?”

“No, I heard that in times of cholera you shouldn’t change any habits.”

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1865)

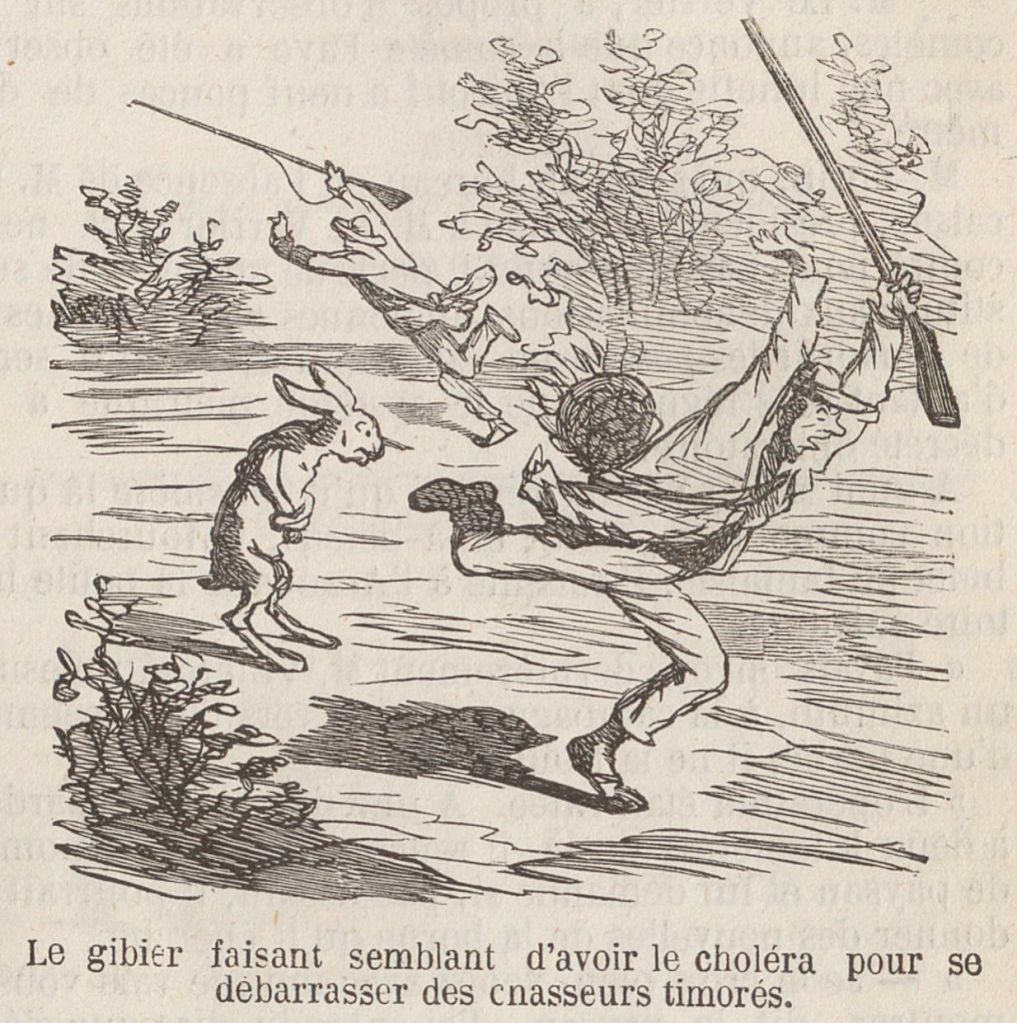

Game pretending to have cholera to get rid of timorous hunters.

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1865)

When Bavarian authorities forbade rabbit hunting during the 1892 epidemic, Kladderadatsch published a similar cartoon.

“You’re afraid of cholera? Manners, my dear. You have the quarantine to preserve you.”

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1865)

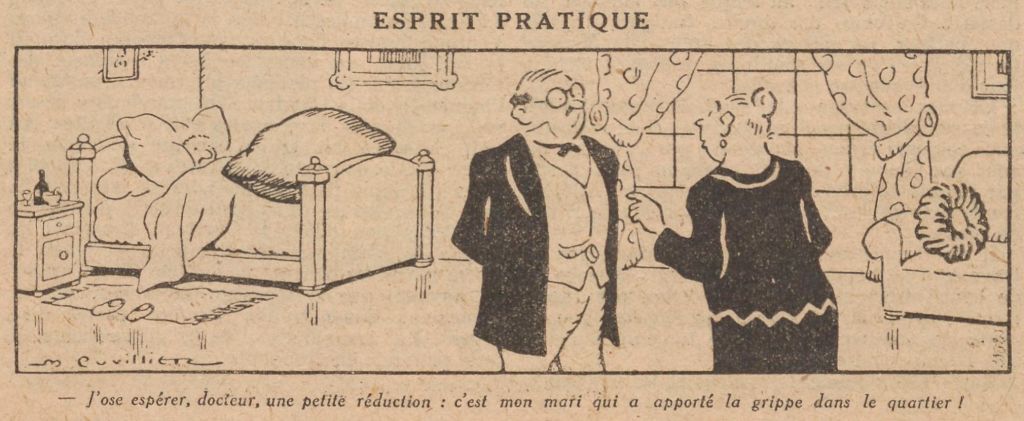

“I dare to hope for a small reduction in your fee, doctor: it was my husband who brought the flu to this neighborhood!”

(Le Petit écho de la mode, Paris, 1927)

Two young men are approached by a prostitute: she is a clothed skeleton holding a made-up mask in front of her face, representing syphilis. Lithograph by J.J. Grandville, 1830.

(Wellcome Collection)

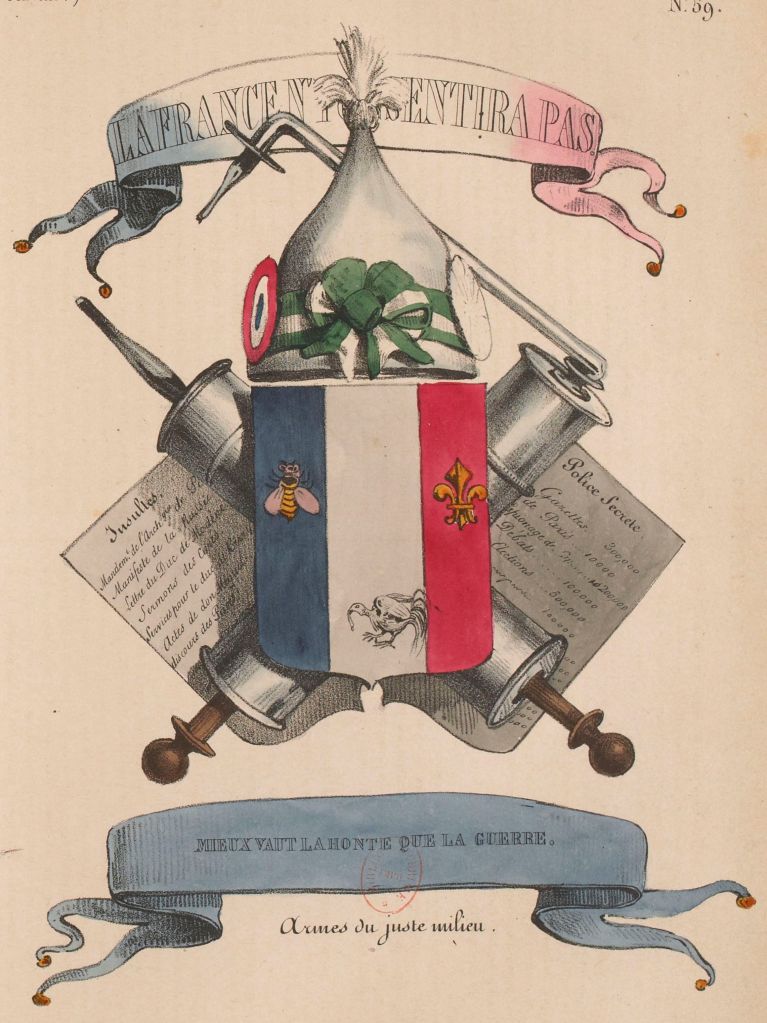

This coat of arms with list of Insults on the left and Secret Police overseeing newspapers and political life on the right prominently features two crossed clystères, syringes suitable for administering enemas. (Note that the one on the right seems designed for self-administration.) At the height of the second cholera epidemic, the slogans at the bottom captured contemporary sentiments: “Better shame than war” and “Judicious moderation in arms.”

(La Caricature, Paris, 1831; this was a recurrent theme)

The constitutional monarchy created by the July Revolution of 1830 had placed a distant cousin from the House of Orléans on the French throne, an arrangement supported more by the liberal bourgeoisie than by royalists. This image would appear to comment ironically on the reinvention of monarchical icons of rule, something I cannot evaluate more broadly. But there is one element that does concern us, the giant clystère at center left, a syringe suitable for enemas. (Not the first time we have encountered this.) Paris was struggling with the worst of the second cholera pandemic at the time, so it remains for me to understand more precisely why this epidemic icon was incorporated in this satirical image. (La Caricature, Paris, 1831)

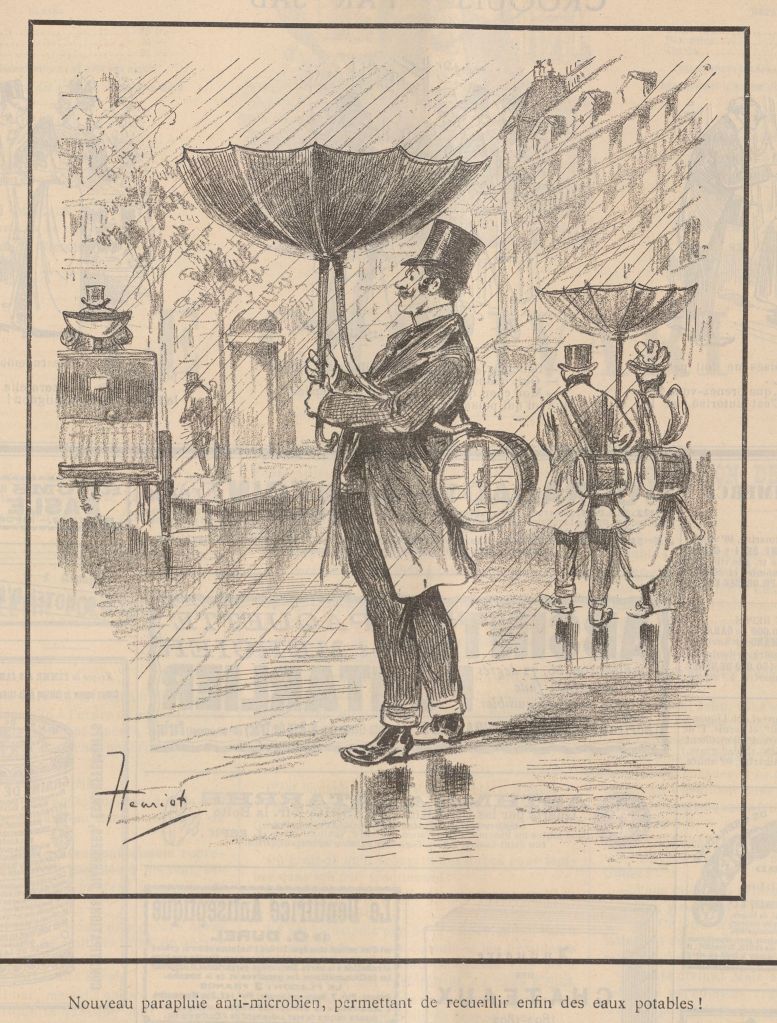

New antimicrobial umbrella that finally lets you collect potable water!

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1892)

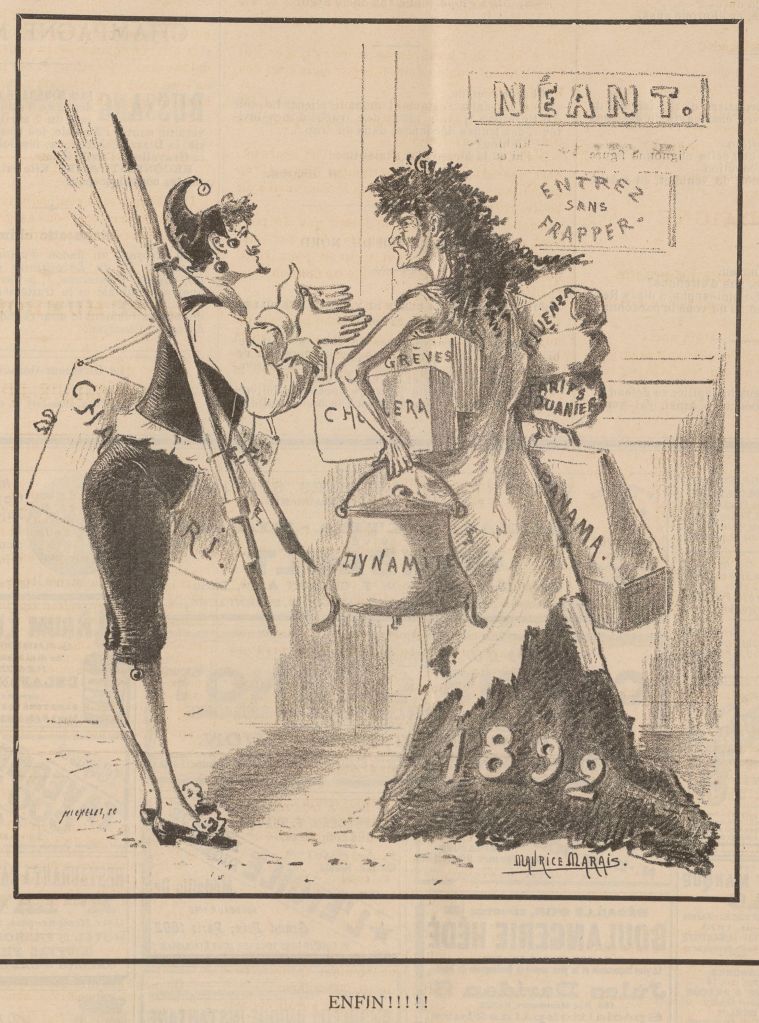

The year 1892 finally exits the store carrying her acquisitions: dynamite, cholera, strikes, influenza, tariffs, and the Panama Canal scandal.

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1892)

I’m overreaching here, but I find this connection oddly amusing. First: Eugène Sue began publishing the serial novel The Wandering Jew in 1844, and it enjoyed great popularity in Paris. Although it made reference to the legendary figure who taunted Jesus on the way to crucifixion, the central thrust of the novel, set in 1831, was rather more anti-clerical. The intrigues of a Jesuit named Rodin figure strongly, while epidemic cholera drives goodly portions of the plot. Eventually Rodin himself is seized with the cholera, and Sue narrates a scene of carts filled with coffins clattering down city streets at night, invoking “the joyous strains of the grave diggers; public-houses had sprung up in the neighborhood of the churchyards, and the drivers of the dead, when they had “set down their customers,” as they jocosely expressed themselves, enriched with their unusual gratuities, feasted and made merry like lords; dawn often found them with a glass in their hands, and a jest on their lips; and, strange to say, among these funeral satellites, who breathed the very atmosphere of the disease, the mortality was scarcely perceptible.” The “dregs of the Paris mob” would gather near the main hospital and mock the vain ministrations of the physicians. As things become unruly, drums are heard in the distance, signaling a call to arms to quash sedition in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. When the drummers emerge from under an archway, an older one collapses, himself the sudden victim of cholera. There are shouts that he has been poisoned, having drunk from a fountain en route, and the expiring drummer is carried away to cries of “Make way for the corpse!” Not long thereafter, “The cholera masquerade” is proclaimed, “one of those episodes combining buffoonery with terror, which marked the period when the pestilence was on the increase…”

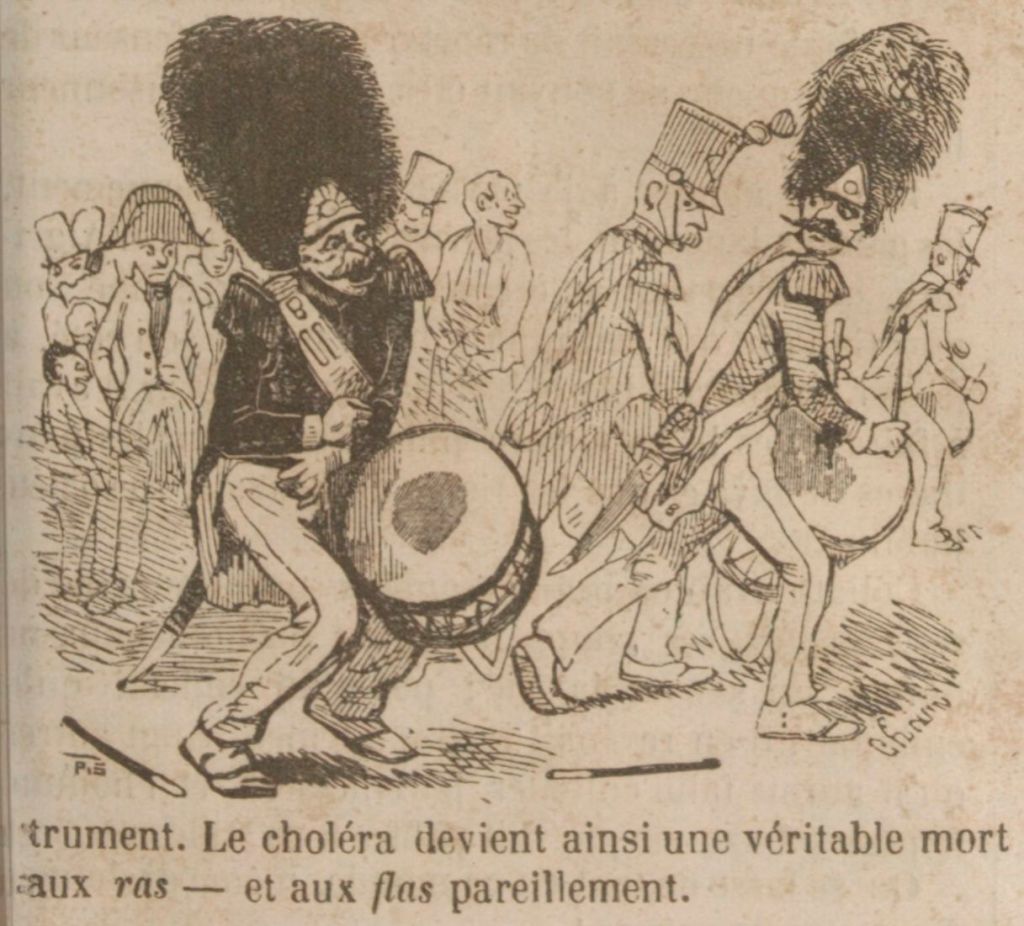

Second: the echo of satire. The French satirical magazine Le Charivari appears to have run its own version of “The wandering Jew” in 1845, where we find this scene featuring Rondin (not Rodin) from a chapter entitled “The cholera”: “The colics of Rondin were only the prelude to other, much more general colics, the cholera is definitely in Paris, as well as the death-eaters who earn mad money, who dance a polka of jubilation. The more Parisians rub their stomachs, the more they rub their hands! But what do you want, for these officials the Chemin du Père-Lachaise [along the largest cemetery in Paris] is the road to fortune!

Cholera has become so universal that it no longer respects anything and it even attacks the drums of the National Guard, which ordinarily still fears so much for its skin!

More than one drummer, while striking the beat, cannot finish the tune he has started on his instrument. Cholera has thus become a veritable death on the rim – and likewise on the flam.”

But in this version, when a “society of tramps” organizes the cholera masquerade, they are joined in their rowdy refrains by the Parisian medical faculty.

(Le Charivari, Paris, 1845)

OK, that was a long walk.

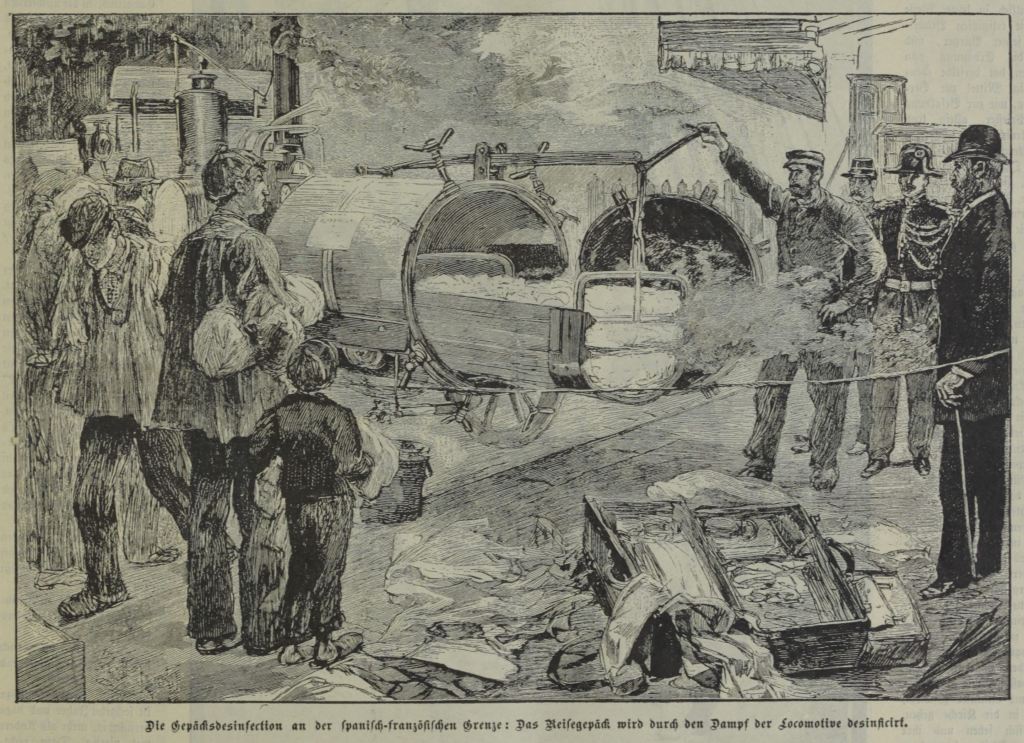

Baggage disinfection at the Spanish-French border: Luggage is disinfected by the locomotive steam.

(Das interessante Blatt, Vienna, 1890)

Illustration by Grandville in La Caricature, undated (c. 1831).

(Gallica)