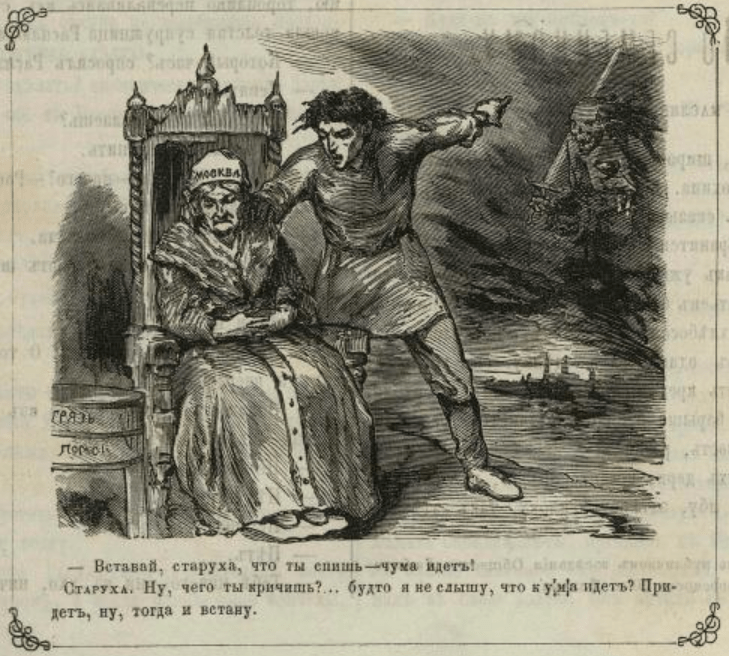

“Get up, old lady [Moscow], why are you sleeping? The plague is coming!”

Old lady: “Why are you shouting? As if I don’t hear the plague coming? When it arrives, I’ll get up.”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1879)

“Get up, old lady [Moscow], why are you sleeping? The plague is coming!”

Old lady: “Why are you shouting? As if I don’t hear the plague coming? When it arrives, I’ll get up.”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1879)

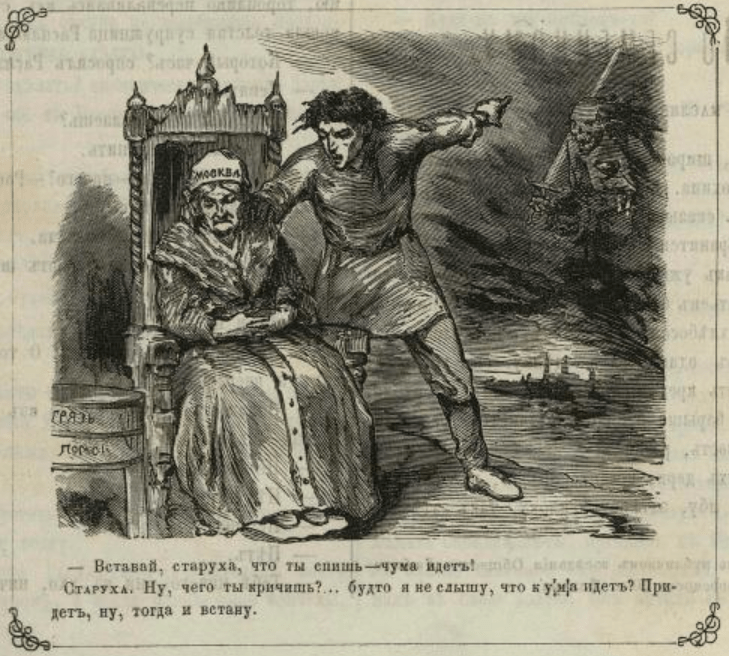

At home: “Oh, my goodness, Mama, why do I have to get a smallpox vaccination? It’s embarrassing: the doctor will see my naked arm!”

At the ball: “I’m very grateful, doctor, that you want to rid me of this shawl: it’s making me so warm…”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1873)

(See Spanish, Czech, Polish, and Swedish variants on this sexist theme.)

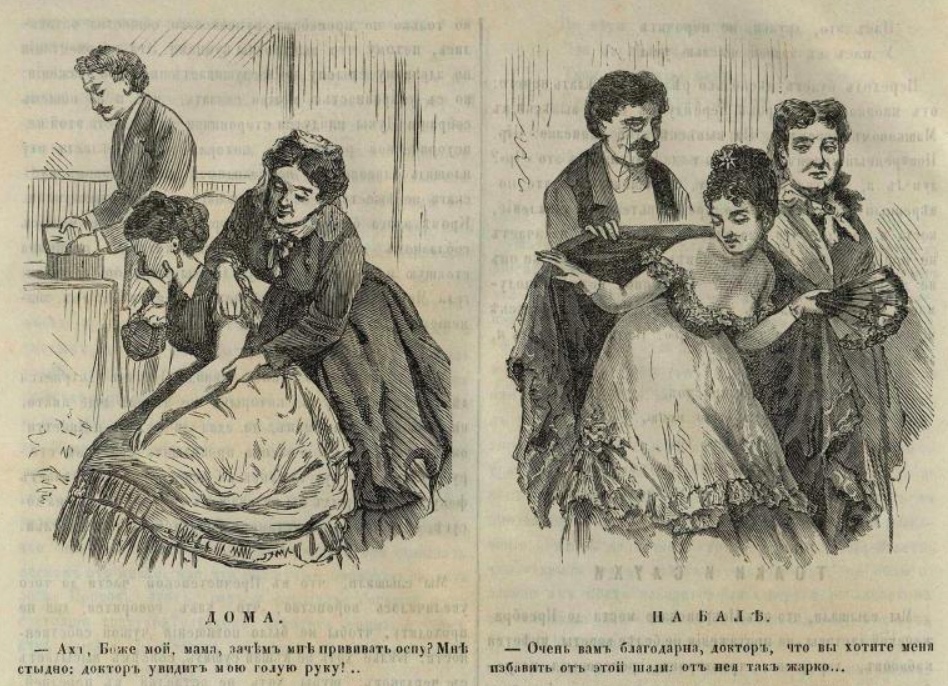

Wife: “All the newspapers are talking about cholera. I’m afraid! Are you afraid, sweetie?”

Husband-doctor: “Yes, I’m afraid… that it’ll never reach us…”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1883)

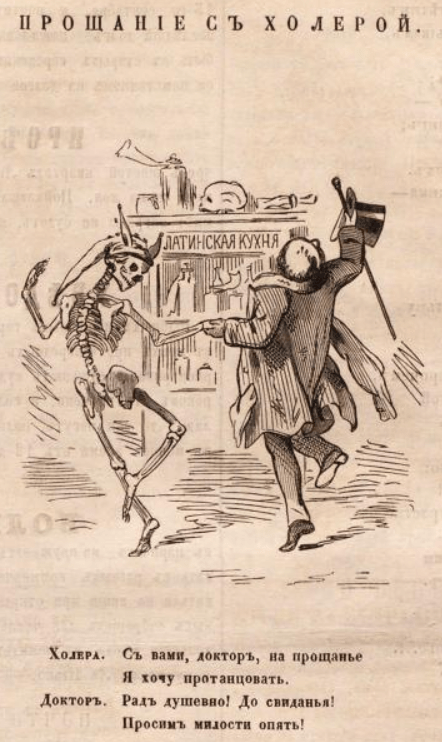

Cholera: “I want to dance with you,

doctor, in parting.”

Doctor: “It’s my pleasure. Good bye!

May you grace us again!”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1871)

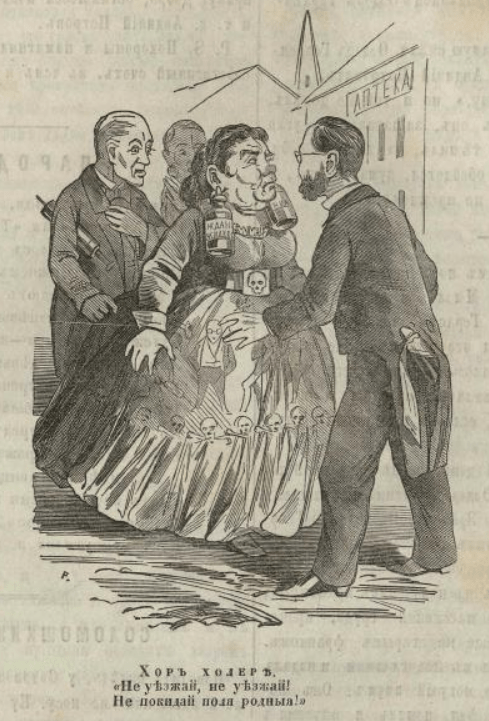

“Don’t leave us, don’t leave us! Don’t leave your native lands!”

(Sign in the background signals that pharmacists are singing the lament. Note the clystère under one pharmacist’s arm, a recurring theme.)

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1866)

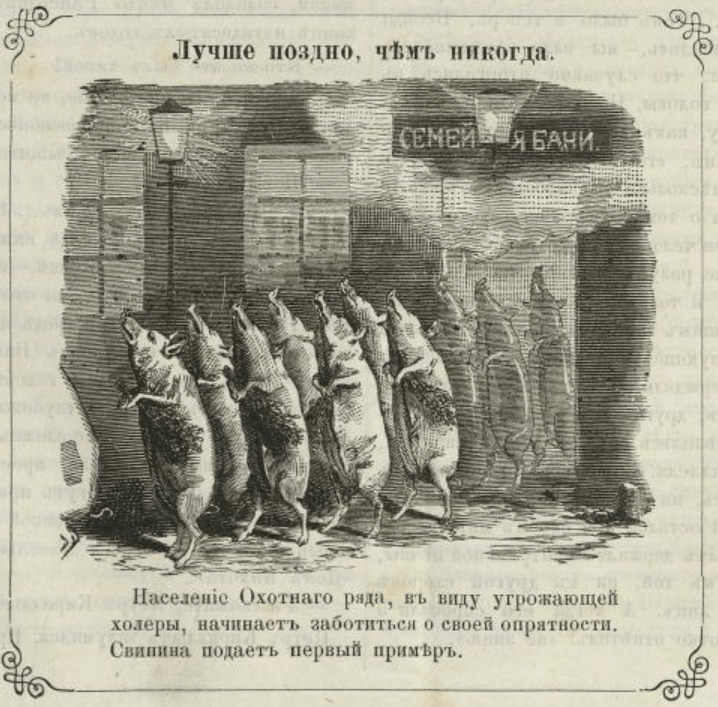

The population of Hunter’s Row [in central Moscow], in view of the cholera threat, are starting to take care about their cleanliness. Swine provide the prime example [passing through a Moscow sauna].

(Several years later the municipal authorities would construct a major public abattoir, motivated in part by public health concerns, as you can learn from the work of Anna Mazanik.)

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1883)

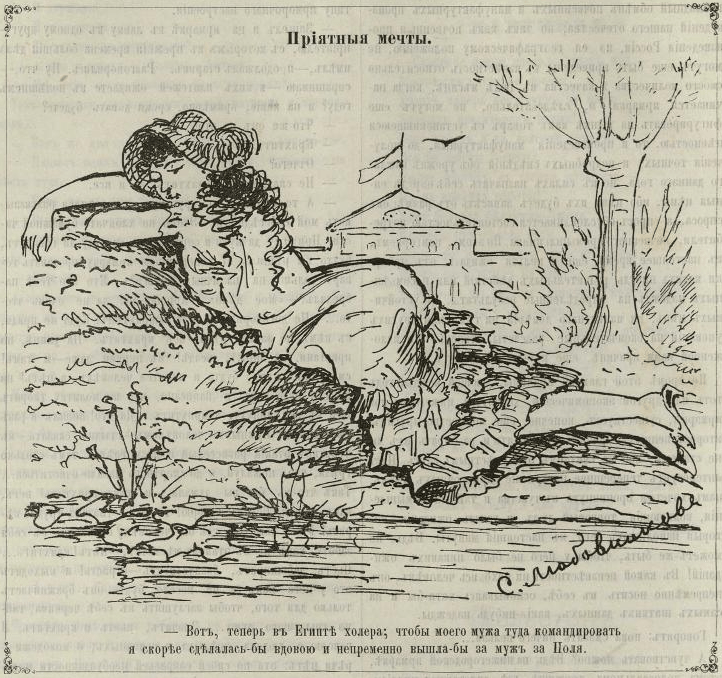

“Now there’s cholera in Egypt; were my husband to be assigned there, I would quickly be made a widow and immediately get married to Paul.”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1883)

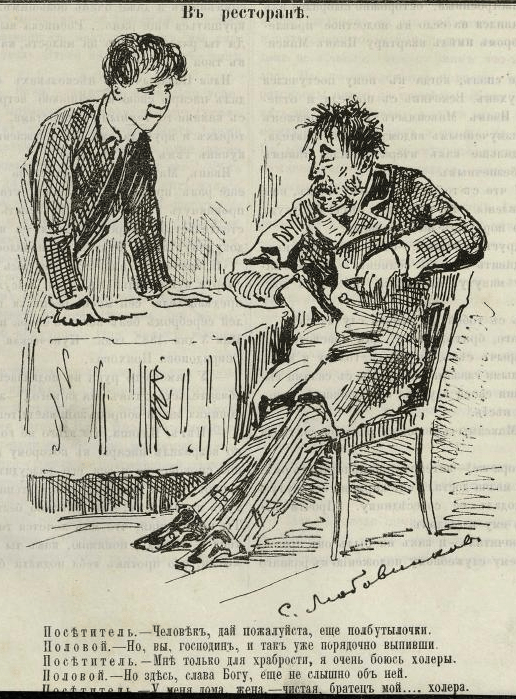

Visitor: “Man, gimme another half bottle, please.”

Waiter: “But you, sir, are already properly soused.”

Visitor: “It’s just for courage, I’m really afraid of cholera.”

Waiter: “But thank God we haven’t heard anything about it here.”

Visitor: “At home my wife is clean, and my brother is… cholera.” [presumably the usual wordplay about “choleric”?]

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1883)

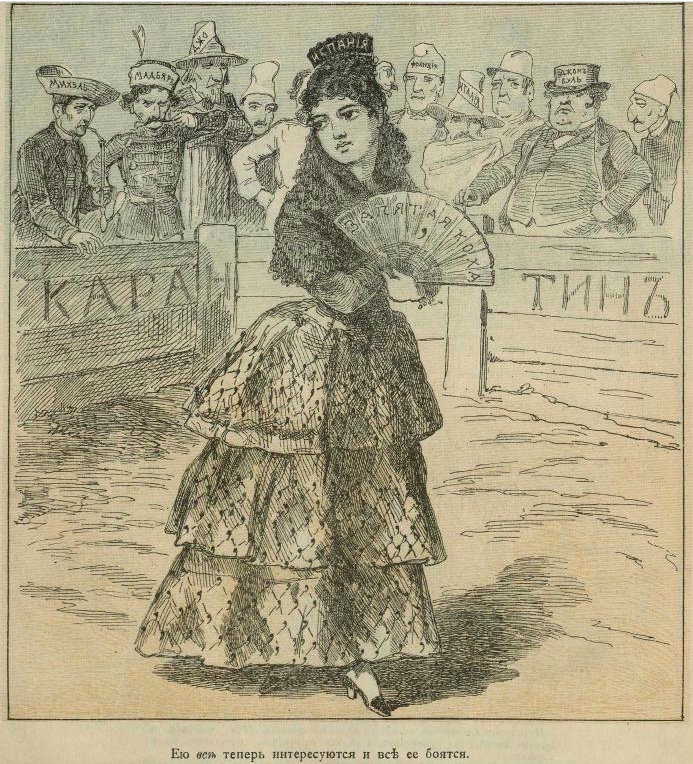

(Young woman outfitted as Spain, carrying fan labeled “Koch’s comma,” a reference to the cholera vibrio. She stands in an enclosure marked “quarantine,” with onlookers Hungary, Italy, John Bull, et al.)

Everyone is interested in her now, and everyone is afraid of her.

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1885)

Accompanied by famine and cholera.

(Iumoristicheskii al’manach, Moscow, 1908)

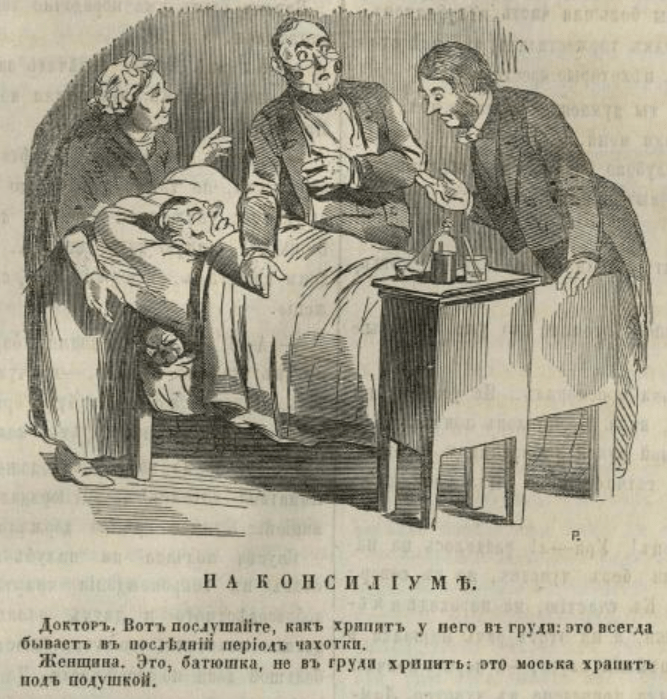

(From the annals of diagnostic nihilism)

Doctor: “Listen here to how his chest is wheezing: you always get this in the final stage of consumption.”

Woman: “It’s not wheezing in his chest, mister: it’s a pug snoring under the cushions.”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1866)

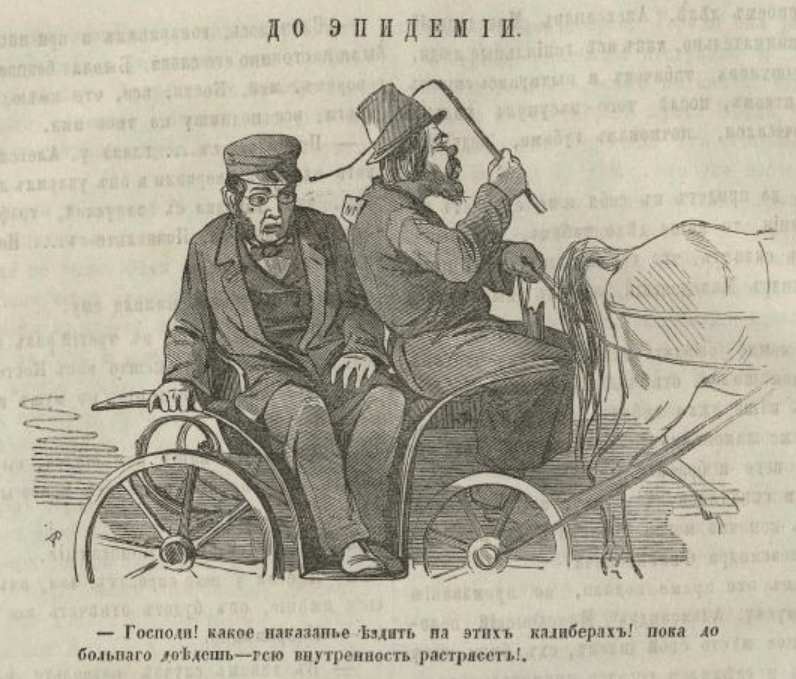

“Heavens! Such punishment to ride in these tiny carriages! By the time you get to the patient, all your insides will get shaken up!”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1866)

Cholera made them relatives,

Smallpox gave them brotherhood,

Death united them forever

And called them friends.

Their visit dismays people,

They all know this truth:

That one will put us in the grave,

This one will dump us under the slab.

Because you won’t die without them,

And all outcomes will end up

being those that you will call

directly by the name: twins.

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1874)

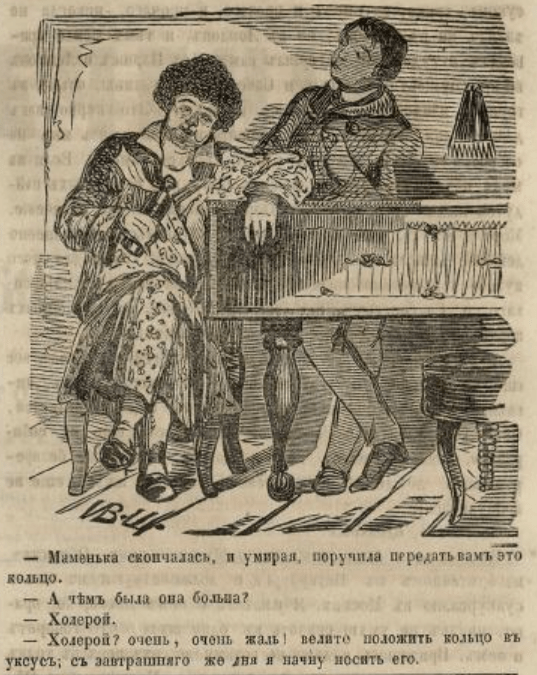

“Mamma passed away, and as she was dying, she instructed me to give you this ring.”

“What was she sick with?”

“Cholera.”

“Cholera? Such a pity! Tell them to put the ring in vinegar, and I’ll start wearing it tomorrow.”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1860)

“It’s pointless not to believe in medicine, madam…”

“To believe in a science which is powerless to invent the kind of illness whose treatment requires a trip to Yalta [on the Crimean peninsula]?! And this is science? Phooey!”

(Razvlechenie, Moscow, 1895)